The Dollar's Self-Defeat and Why Schools Will Pay for It

Input

Modified

The dollar’s slide is a self-inflicted wound from tariffs, aid cuts, and fiscal drift Market confidence punished these choices, raising costs for campuses and squeezing budgets Fix it with boring credibility: a real fiscal path, rules-based trade, and strategic re-engagement

In the six months leading up to June 2025, the U.S. dollar index declined by approximately 11%, marking one of the most significant half-year declines on record, before stabilizing in late summer. Markets didn't suddenly forget America's strengths. Instead, they reevaluated a policy mix that increased prices at home, invited retaliation abroad, and raised doubts about the nation's fiscal future. Currency traders may not be moralists, but they act quickly. As tariffs expanded and temporary waivers appeared and disappeared, speculative positions became more negative, leading to the dollar's decline. Confidence, our cheapest source of capital, fades quickly when rules turn into improvisation. A weaker dollar can sometimes benefit exporters, but when it results from erratic decisions that harm our supply chains and reduce U.S. influence, it creates a costly type of weakness. We can already see the impact on education budgets, research labs, and international enrollment plans. The situation is clear because the evidence is strong: the dollar's decline is not an enigma in the markets; it is the predictable result of choices made in Washington. For education budgets, the weaker dollar means increased costs for imported educational materials and equipment, putting a strain on the already tight budgets of schools and universities.

How the Dollar Lost Ground

This year's strategy relied on unilateral tariffs and the suspension of duty-free "de minimis" imports, presented as a means to achieve reciprocity. In April, Executive Order 14257 implemented a "reciprocal tariff" system, which essentially meant that the U.S. would impose tariffs on imports from countries that impose tariffs on U.S. exports. By late July, a second order was issued to suspend duty-free de minimis treatment worldwide, with Customs and Border Protection setting August 29 as the enforcement date. These actions significantly increased the effective tariff burden in a way not seen for decades and created a fluctuating pattern of exemptions and changes. Markets don't just consider levels; they also react to uncertainty. When the rulebook seems provisional, hedging increases while risk-taking decreases; this combination results in a quick reevaluation of the dollar, despite resilient headline economic data, because traders anticipate what might come next: higher import costs, more retaliation, and greater confusion over the rules.

Fiscal calculations further complicated matters. The Congressional Budget Office projects a 2025 deficit close to $1.9 trillion and growing debt over the next decade. Fitch confirmed the sovereign rating at AA+ in August, but noted persistent large deficits and a rising interest burden. In simple terms, temporary tariff gains do not resolve structural issues. The dollar's decline mid-year and soft performance into September suggested that investors viewed the mix of increasing tariffs, decreasing aid, and rule-based engagement, along with unresolved deficits, as inconsistent with long-term currency strength. Foreign demand for Treasuries remained robust, but the July Treasury International Capital report showed overall net inflows dropping to around $2 billion, a reminder that the underlying composition can shift. The currency reflects credibility; in 2025, that judgment went against us.

The third factor is influence. The administration froze most foreign assistance for review in January and planned to dismantle USAID, transferring functions into the State Department. Regardless of the budgetary intentions, the message to partners was clear: the United States would invest less in the essential connections—like health, development, and university partnerships—that turn dollars into lasting relationships. The IMF's spring outlook highlighted how trade conflicts and policy uncertainty hinder growth. By late summer, various observers warned that high tariffs would cause persistent inflation and slow down growth in 2026. Such a backdrop does not support the strengthening of reserve-currency status; instead, it teaches the world to hedge against U.S. exposure.

The Campus-Level Impact

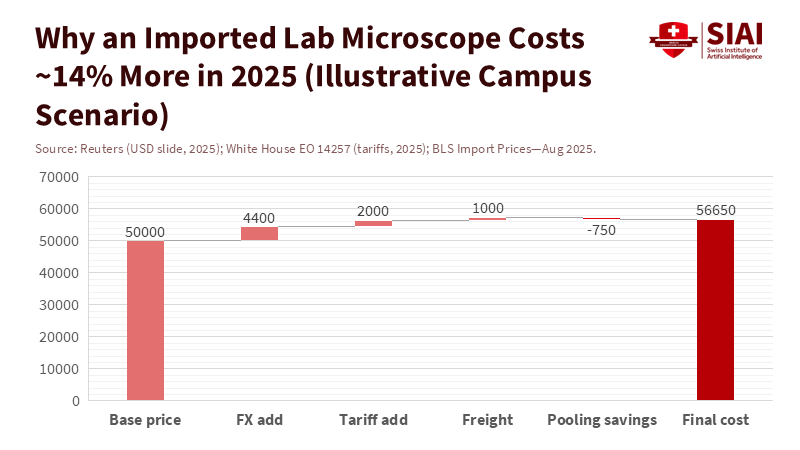

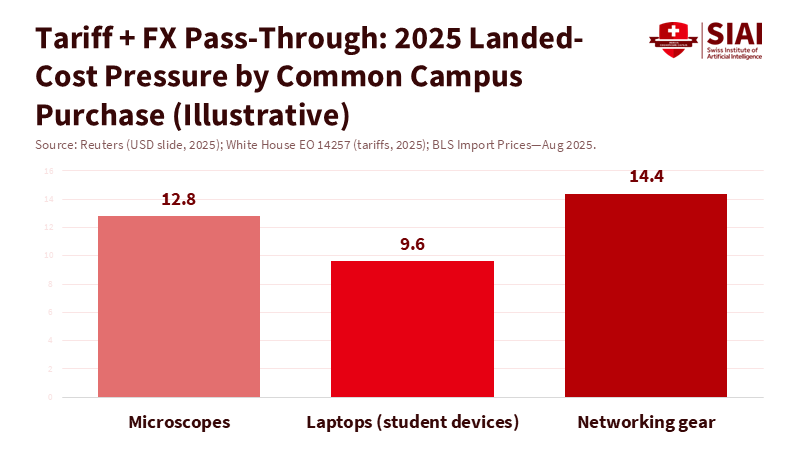

For schools, the drama surrounding exchange rates appears in their budgets. Import-heavy purchases—like sequencing reagents, microscopes, sensors, network equipment, and software—now incur both tariff increases and a weaker-dollar premium. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported a 0.3% rise in import prices in August, following a 0.2% increase in July, mainly due to non-fuel goods. Federal Reserve estimates suggest that tariffs in 2025 alone have put noticeable pressure on core goods prices. When non-fuel import prices increase as the currency weakens, a single procurement cycle can cost 5-10% more, potentially delaying lab updates or limiting device rollouts in K-12 schools. Price indices intentionally exclude duties; the total cost for campuses includes these.

The situation with enrollment is more complex. A weaker dollar can make tuition more affordable for families paying in euros, rupees, or yuan. Open Doors data indicate that the number of international students in the U.S. is at or near record levels for the 2023/24 year. However, students value predictability just as much as price. Visa complications, processing delays, and general rhetoric about openness add real risk. Early commentary from sector groups for 2025 suggests uncertainty regarding fall enrollment figures, and new work visa regulations may offset any currency advantages. In short, a policy blend that seems unstable undermines one of America's key export sectors—education and talent development. The potential consequences include a decrease in international student enrollment, a reduction in the diversity of the student body, and a loss of revenue for educational institutions, even if exchange rates appear favorable on the surface.

Endowments, pensions, and capital projects also feel the broader economic effects. As the Federal Reserve lowers rates and the U.S. yield premium shrinks, foreign hedging of dollar assets may increase, causing the spot dollar to weaken sporadically. July's TIC data revealed a two-part story: foreign holdings of Treasuries were at record highs, but overall net inflows were nearly flat. If this becomes a trend—large gross purchases of safe assets combined with reduced risk appetite for other investments—borrowing costs for campuses may rise, and private funders could become more selective. The impact of this policy unpredictability on universities is not to be underestimated. They can usually withstand a quarter or two of currency fluctuations; they cannot thrive if policy unpredictability turns "hedge the dollar" into a default strategy.

Rebuilding Credibility the Simple Way

The solution to market discipline is not louder demands but steadier rules. A solid fiscal path, crucial for the stability of the education sector, begins with improving revenue: broadening the tax base where feasible, cutting low-return spending, and outlining a medium-term budgetary strategy that does not depend on border taxes to drive lasting reform. That approach builds trust and reassures the audience. On trade, shift from improvisation to negotiated agreements. Using tariffs as a permanent solution teaches partners to bypass us, leading to higher long-term costs. Finally, restore strategic assistance—including health and education partnerships—not as charity but as a wise investment in shaping priorities and standards. Market participants are not sentimental; they reward dependable competence with lower risk premiums and a stronger currency.

Educators and administrators cannot wait for Washington to act. They can manage large purchases in foreign currencies, collaborate on buying to reduce tariff exposure, and diversify suppliers so that total cost—not just headline duty rates—guides choices. They can also broaden revenue sources through joint degrees, micro-campuses, and remote cohorts that rely less on a single visa pathway or currency. In terms of curriculum, they can focus on skills that become increasingly valuable in uncertain times, such as trade compliance, supply chain analysis, data governance, and cross-border finance. These are not emergency adaptations; they are ongoing investments that help institutions manage shocks rather than pass them onto students and staff.

Choosing Strength Over Signal

Two counterarguments are worth mentioning. First, some argue that a weaker dollar benefits exporters and attracts international students; however, this situation is different because the weakness signals policy risk, not the result of productivity-boosting investments. Exporters that depend on imported parts find that higher input costs counter any currency gain. Meanwhile, campuses experience any tuition benefits offset by visa and policy uncertainties. Second, some argue that tariff revenue reduces the deficit and, therefore, strengthens the dollar. Analysts and budget officials have already pointed out this mistake: windfalls do not equate to a plan, and the debt continues to trend upward. Markets understand that increasing taxes and lowering real incomes cannot replace the reforms needed to promote growth. This explains the sharp decline of the dollar, its recovery, and its ongoing vulnerability. Reputations rebuild more slowly than they break.

The education perspective clarifies what is at stake. A dollar weakened for the right reasons—sustained investment that enhances productivity—means better labs, more affordable devices, increased research, and broader access. A dollar weakened for the wrong reasons—policy shifts that hurt ourselves and diminish our influence—results in delays in procurement, hiring freezes, and fewer opportunities. We do not need a heroic solution; we need discipline: a clear fiscal plan, a return to negotiated trade policies, and strategic engagement abroad that rebuilds respect for U.S. institutions. Schools should take action where they can—by hedging, pooling, diversifying, and teaching skills for a world of uncertainties—because strength developed on campus is the most enduring kind we possess.

We started with an 11% decline because it captures a tumultuous year in a single message: confidence cannot be coerced; it must be earned. The current policy mix—tariffs that harm us, reduced aid that weakens alliances, and drifting deficits—has invited the market's judgment. The way back is straightforward and unexciting: make fiscal calculations credible, restore trade to established rules, and invest in the relationships that support the dollar's role. If we follow this path, the next significant statistic will not be another steep currency drop; it will be the quiet return of trust, reflected in our bonds, demonstrated in more stable budgets, and evident in classrooms that are equipped on time and within budget. That is the only kind of strength worth signaling—and the only one markets will reward.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Amiti, M., Redding, S. J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2019). The impact of the 2018 tariffs on prices and welfare. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 187–210.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025). U.S. import and export price indexes—August 2025 (news release and tables).

Congressional Budget Office. (2025, January 17). The budget and economic outlook: 2025 to 2035.

Customs and Border Protection. (2025, August 29). CBP ready to enforce end of de minimis loophole.

Fajgelbaum, P. D., Goldberg, P. K., Kennedy, P. J., & Khandelwal, A. K. (2020). The return to protectionism. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(1), 1–55.

Fitch Ratings. (2025, August 22). Fitch affirms the United States of America at 'AA+'; outlook stable.

International Monetary Fund. (2025, April). World Economic Outlook: A critical juncture.

Institute of International Education (IIE). (2024, November 18). U.S. hosts more than 1.1 million international students at higher education institutions—All-time high.

Reuters. (2025, June 18). Dollar exit could be crowded for some time.

Reuters. (2025, September 11). U.S. dollar bears think record slide may resume after recent pause.

Reuters. (2025, September 16). U.S. import prices increase in August on capital, consumer goods.

Reuters. (2025, September 18). Foreign holdings of U.S. Treasuries surge to all-time high in July, China's sink.

Surowiecki, J. (2025, May 8). The impending doom of Trump's trade war. The Atlantic.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2025, September 18). Treasury International Capital (TIC) data for July 2025 (press release).

White House. (2025, April 2). Executive Order 14257—Regulating imports with a reciprocal tariff to rectify trade practices that contribute to large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits.

White House. (2025, July 30). Suspending duty-free de minimis treatment for all countries.

White & Case. (2025, August 5). United States to suspend customs de minimis entry for most shipments August 29, 2025. (Client alert).

KFF. (2025, September 10). U.S. foreign aid freeze & dissolution of USAID: Timeline of events.

Federal Reserve Board. (2025, May 9). Minton, R., & Somale, M. Detecting tariff effects on consumer prices in real time (FEDS Notes).