When Extra Information Helps: A Bayesian Information Update Test for Central Bank and School Communication

Input

Modified

Extra information helps only when it adds new, orthogonal signal and is easy to process Central banks and schools should use plain anchors and concrete rules to trigger a Bayesian information update Measure belief shifts, not word counts, and iterate when messages fail to move the posterior

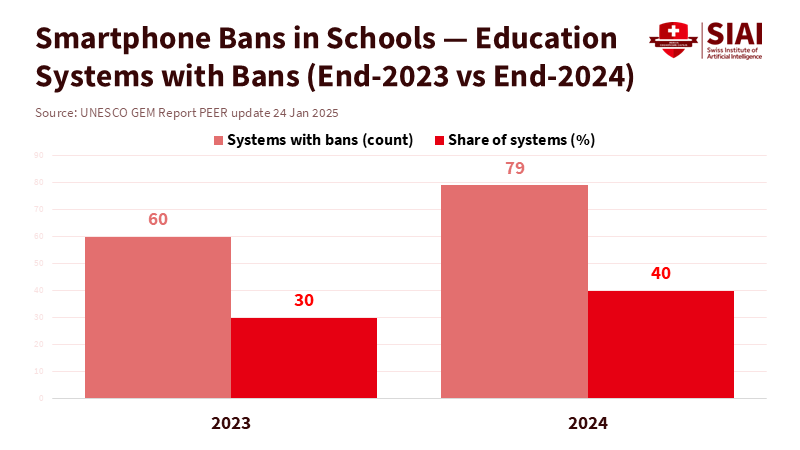

Seventy-nine. By the end of 2024, 79 education systems, about 40% of the world, had banned smartphones in schools. The headline sounds decisive, yet policy only changes behavior when the message adds new value to what people already believe. This is the essence of a Bayesian information update: extra information only helps decisions if it differs from existing beliefs and is easy to process. Central banks learned this during the inflation surge and retreat. Lengthy statements nudged markets, but households and firms often stuck to their previous beliefs. Schools face a similar challenge as they try to regulate phones and classroom AI. The lesson is straightforward: treat each announcement as a signal-processing problem. Suppose the following sentence does not change beliefs. In that case, it is just noise, no matter how well-intended the communication may be. UNESCO’s number is striking; the impact test is stricter. Do citizens update? Do students and parents update? If not, say less and say it better.

Why a Bayesian information update is the proper test for “more information”

The most lasting insight from modern communication research is that attention is limited and expensive. In economics, this idea is formalized as rational inattention: people choose what to focus on and conserve attention when the reward is low or the message is hard to understand. In simpler terms, when a message is too complex or the potential benefit of understanding it is low, people tend to ignore it. In these situations, an announcement that repeats old content will not change beliefs or behavior because it adds no new signal. A Bayesian information update occurs when the message includes independent content that people have not yet considered. That is why simple, clear anchors tend to work better than long explanations; they fit neatly into existing ideas and adjust them by a measurable amount.

Central bank communication illustrates this logic in real time. When the European Central Bank or the Federal Reserve repeats old guidance in dense language, financial markets react quickly, but households barely respond. In contrast, messages that introduce a new, credible anchor—such as a clear 2% target explained in simple terms—can narrow the distribution of medium-term expectations. Recent experiments highlight this point. Direct, personal briefings at the ECB Visitor Centre improved understanding and aligned expectations with the target, especially among people with little knowledge of policy. Clear and matching language reduced the cost of attention and increased the reward of listening. In short, the difference and simplicity of the Bayesian information update enable the public to use it.

What the data say: the Bayesian information update in practice

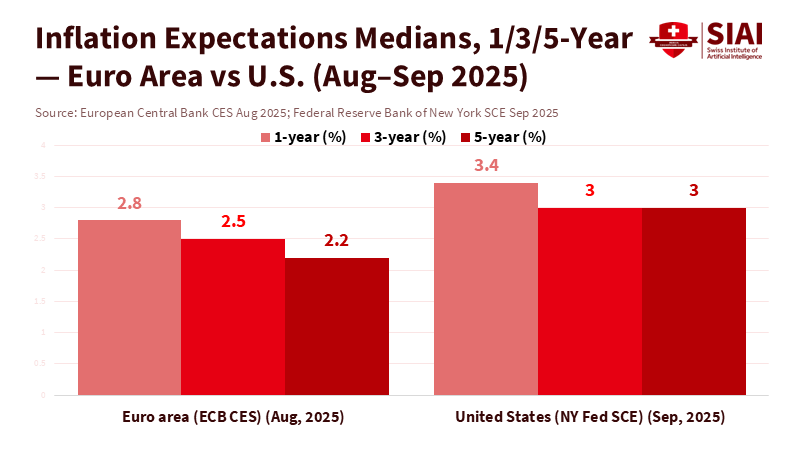

Throughout 2025, euro-area consumers’ beliefs show how anchors work—and where they fail. In August, the ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey reported a median one-year inflation expectation of 2.8%, a three-year expectation of 2.5%, and a five-year expectation of up to 2.2%, the highest since August 2022. The near-term expectation still drifted above the target. Still, the longer-term expectation remained close to 2%, indicating that repeated, simple reminders about price stability help anchor medium-term expectations even when current prices fluctuate. Stability at three years with a slight rise at five years is precisely what a partial update looks like: people hear the target, remember it, and combine it with recent price experiences.

The United States provides a valuable contrast. In September, the New York Fed’s Survey of Consumer Expectations reported a one-year median expectation of 3.4%, with three-year and five-year expectations around 3.0%—still above the Fed’s 2% goal. Meanwhile, the University of Michigan survey showed year-ahead expectations in late summer between 4.7% and 4.9%. Two reputable surveys provide different snapshots but share one standard signal: households with limited time and uneven financial literacy update slowly and selectively, sometimes prioritizing lived prices over official guidance. This divergence is not a failure of surveys; it serves as a reminder that most people will not perform a full Bayesian update unless the message is straightforward, significant, and new.

Firms behave similarly. New evidence from a large-scale survey of U.S. companies finds that many managers hold weak expectations about inflation and monetary policy, and their beliefs often remain unanchored due to a lack of clear communication. Where firms receive straightforward, credible signals, expectations align more closely with targets; where they do not, pricing plans continue to reflect uncertain narratives. A 2025 research review reaches a similar conclusion: the expectations of many agents are only loosely connected to official goals, and the path from policy to beliefs depends on how the message is designed. The key takeaway for policy is clear: if the audience is inattentive, adding more complexity does little good. However, providing clear, relevant content does a lot. This emphasis on the role of explicit, relevant content in shaping beliefs should make the audience feel informed and empowered, helping them understand the impact of their communication strategies.

From central banks to classrooms: designing a Bayesian information update for schools

Education leaders face the same challenge of balancing signal and noise. Smartphone rules are quickly spreading, yet compliance and classroom focus depend on whether these rules offer families something new to consider. The global count of 79 systems with bans by the end of 2024 is striking. Still, success comes from rules that add clear signals: for example, specifying lockable pouches, designated storage areas, or set release times. These details are distinct from generic “no phones” messages. They reduce interpretation costs and increase the chances of a real Bayesian information update in the minds of parents and students. Where the rule is vague or framed as a moral appeal, behavior does not change much because beliefs barely shift.

There is also a cautionary note. A quick review of evidence finds that many school phone policies are based more on beliefs than on solid data, and that their effects vary by context. This is not a reason to avoid action. It is a push toward better message design and improved measurement. Taking a cue from central banking: publish a clear, simple anchor (“no phones during lessons”), pair it with a solid enforcement mechanism (“locked pouches from the start bell to the end”), and communicate in a way that resonates with the audience. Where authorities have tried simple, targeted messages—similar to the ECB field experiments—understanding and trust have increased. These are essential conditions for a lasting Bayesian information update. Emphasizing the need for better message design and improved measurement in school policies should motivate the audience to feel proactive and understand the potential impact of their actions.

Policy playbook: measuring a Bayesian information update and acting on it

The first step is to define success as movement in beliefs—not the number of words. For central banks, the “posterior” is shown in the distribution of one-, three-, and five-year expectations. In the euro area, the five-year median near 2.1–2.2% has remained slow and stable, even as one-year expectations fluctuate with news and grocery bills. This indicates that simple anchors are effective over the medium term. It also signals where communicators should focus: address short-term concerns using fresh, relevant facts—like decreasing energy costs or slowing wage growth—rather than repeating mandates. For school systems, the posterior is reflected in family surveys and classroom observations: do parents and students expect different behavior on Monday than they did on Friday? If not, the message did not add new value.

Second, make it easier to pay attention. Studies tracking the clarity of ECB leadership speeches show that simpler language enhances understanding. At the same time, work from the Bank of England illustrates how complex information often fails to reach non-experts. The same is true for school memos and ministry directives: use fewer clauses, shorter sentences, and one action per paragraph. Matching the audience’s language, both literally and figuratively, matters too; in the ECB field experiment, removing language barriers intensified the impact on expectations. People cannot update on information they do not fully comprehend. Plain language is not just a stylistic choice; it is a communication tool.

Third, aim for difference. The expected value of a message is high when it introduces new information that the audience has not already considered. For monetary policy, this might mean providing a straightforward, credible timeline for the target rather than a complex forecast. For schools, this could involve transitioning from a general “AI is allowed for learning” statement to a clear, age-appropriate rule. This rule would include specific examples of allowed uses for writing outlines, explicit bans on essay generation for grades, and visible checks for misuse. Each of these components represents a different aspect of information. The posterior shifts because families learn something they did not already assume from headlines.

Finally, close the loop. Central banks now conduct regular expectation surveys and publish the results. Education systems can do the same at a low cost: a three-question survey each term for students, teachers, and parents. Ask about expected phone use in class, expected AI use for assignments, and expected enforcement. If beliefs do not change, adjust the message—not the mission. The goal is not to overwhelm inboxes but to deliver fewer, clearer signals that prompt a Bayesian information update. The record—from the ECB’s monthly consumer survey to the New York Fed’s SCE—demonstrates the best ways to track that movement and when to make changes.

The question “Does extra information help people make better decisions?” has a clear answer: it does, but only if the information changes their beliefs and is easy to absorb. In a world overflowing with words, the winning strategy is to make each message pass the Bayesian information update test. Central banks that repeat their mandates without adding new signals observe households clinging to unclear beliefs. At the same time, those who explain the target and path in simple terms see medium-term expectations align with what is needed. School systems that announce bans without specifying procedures face constant workarounds; systems that provide concrete, precise details—what is allowed, when, and how it is enforced—change classroom behavior. The statistic that started this column—79 education systems with phone bans—marks a significant moment. The call to action is tougher: design every announcement to shift beliefs. When the signal overcomes the noise, decisions improve; when it does not, say less and say it better.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bjerkander, L., & Glas, A. (2024). Talking in a language that everyone can understand? Clarity of speeches by the ECB Executive Board. Journal of International Money and Finance, 149.

Candia, B., Coibion, O., & Gorodnichenko, Y. (2024). The inflation expectations of U.S. firms: Evidence from a new survey. Journal of Monetary Economics, 145.

Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y., & coauthors. (2025). Inflation, Expectations and Monetary Policy: What Have We Learned Since 2020? NBER Working Paper No. 33858.

European Central Bank. (2025, Sept. 26). Consumer Expectations Survey results – August 2025. Press release.

European Central Bank. (2025). Consumer Expectations Survey (CES) overview page.

Jung, A., Mongelli, F. P., & Scherf, C. (2025, Sept. 16). ECB visitors – can direct communication alter inflation expectations? ECB Blog.

McMahon, M., et al. (2023). Getting through: communicating complex information. Bank of England Staff Working Paper.

New York Fed. (2025, Oct. 7). Short-Term Inflation Expectations Continue to Tick Up; Labor Market Expectations Deteriorate. Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE) release.

PIIE. (2023). Central banks and policy communication: How emerging markets have caught up. Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper.

Sims, C. A. (2003). Implications of rational inattention. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(3), 665–690.

SUERF. (2025). A KISS for central bank communication in times of high inflation. SUERF Policy Note.

UNESCO. (2025, Jan. 24). Smartphones in school: only when they clearly support learning (update on bans to end-2024).

University of Michigan, Surveys of Consumers. (2025). Year-ahead and long-run inflation expectations, August–September 2025.

Working Paper Series No. 3103 (ECB). (2025). Central bank communication with non-experts: insights from a randomized field experiment.