Europe’s Missed Multiplier: how software investment and productivity rise together, and why work culture still matters

Input

Modified

Europe lags by undervaluing software Software investment and productivity must grow together Skills and management close the gap

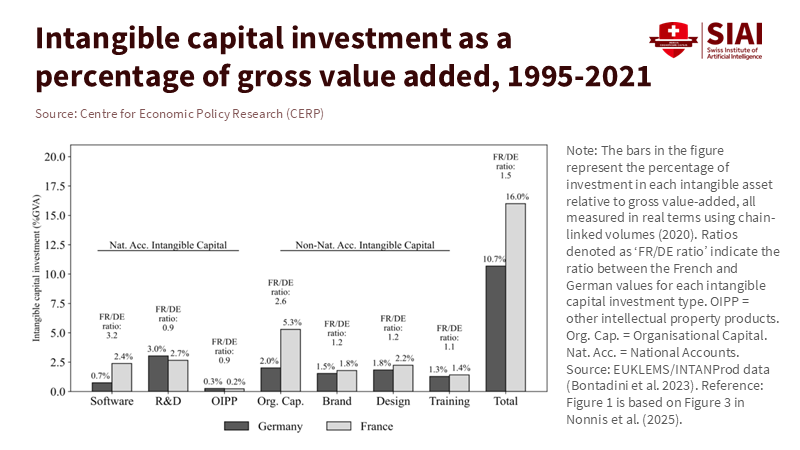

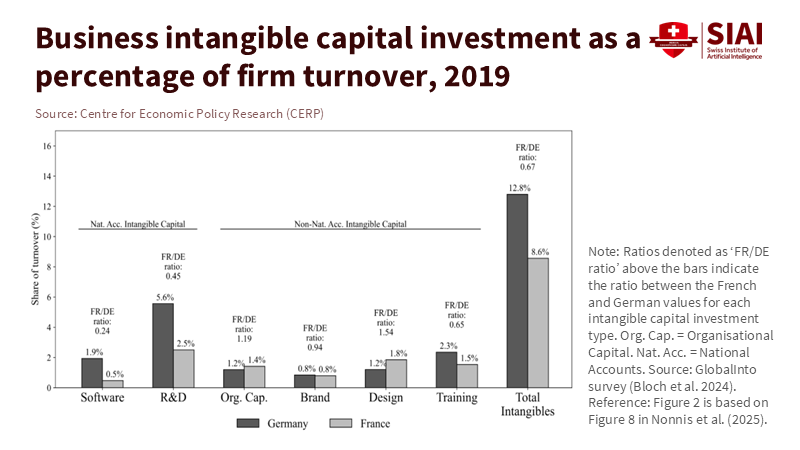

If two neighbors buy the same machines but only one installs the software, who gets ahead? In 2023, France dedicated approximately 2.4% of its GDP to software, while Germany allocated around 0.7%. Meanwhile, Germany’s organizational capital—the routines and management expertise in firms—was measured at two and a half times that of France. Organizational capital, in this context, refers to the skills, knowledge, and processes within a company that contribute to its productivity and efficiency. This accounting choice matters. When we overlook the software that powers the machines, we fail to explain the growth those machines can achieve fully. The bigger picture involves both elements; software investment and productivity work together when systems support quick adoption, fast iteration, and rapid decision-making. Continental Europe protects time off and worker health, and it should continue to do so. However, the benefits of software are highest when digital tools meet skilled users, effective institutions, and work rules that prioritize speed. For Europe to achieve a fairer and wealthier economy, it must combine its human-centered approach with a stronger software foundation.

Reframing the gap: beyond assets to complements in software investment and productivity

Many believe that Europe lags behind the United States due to lower investment in intangibles, such as software, data, and ideas. Intangibles, in this context, refer to assets that lack physical substance but contribute significantly to a company's value, such as software and data. While this view has merit, it is also incomplete. It treats “software versus organizational capital” as a budget issue, considering that productivity relies on how these assets combine with management quality, skills, and time management. Recent analysis identifies four key factors contributing to the long-term gap: lower R&D efforts, reduced investment in intangible assets, slower market growth, and decreased foreign direct investment (FDI). In 2021, the U.S. invested 77% more in R&D than the EU; from 2015 to 2020, U.S. investment in ICT equipment surged ahead. Intangibles now exceed tangibles on both sides of the Atlantic. Still, the U.S. share of intangible investment in gross value added is around 23%, compared to about 17% in core euro area economies, showing a deeper tech diffusion mechanism. The takeaway is not that Europe should abandon its labor model, but rather that the returns from software investment and productivity depend on institutions that enable the quick deployment, usage, and improvement of code.

A second issue involves measurement. Recent studies on France and Germany illustrate how growth accounting varies depending on how we account for code and culture. France invests about three times Germany's share of GDP in software, while Germany reports much more organizational capital. Since organizational capital is challenging to observe, analysts often estimate it based on wages in specific occupations. This can inflate the “management” portion and understate the role of software. The solution is not to ignore organizational capital—it is essential—but to adjust for undervalued software, including software developed in-house, where official statistics may lag behind. U.S. data reveal the scale of the issue: software falls under intellectual property products, which made up about 5.5% of nominal GDP in Q1 2024. Data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis shows rising spending on custom and in-house software through 2023. When software is mismeasured, the productivity landscape becomes unclear, which influences policy decisions. This underscores the importance of accurate measurement in decision-making, making policymakers feel responsible and diligent in their roles.

What the numbers actually say about software investment and productivity

First, let's look at the cross-country picture. Using growth accounting and firm-level data, European analysts find that one-fifth of growth in intangible capital typically flows into total factor productivity (TFP). The U.S. invests more in intangibles, starts earlier in the cycle, and benefits from a more dynamic market that reallocates resources from less efficient firms to more efficient ones. By 2019, the contribution of ICT services to U.S. value-added growth greatly exceeded that of the euro area. In this context, the France-Germany comparison is revealing: 2.4% of GDP in software for France compared to 0.7% for Germany translates not only into greater capital depth but also into smoother adoption of AI, data pipelines, and workflow automation—the very tools that eliminate bottlenecks in schools, hospitals, public agencies, and factories.

Second, the U.S. benchmark helps clarify scale. Private fixed investment in intellectual property products— which includes software—comprised about 31% of private fixed investment and 5.5% of nominal GDP in early 2024. Within that, data from the BEA and FRED indicate steady growth in custom and in-house software through 2023, demonstrating that much of this “software capital” is developed internally rather than purchased off the shelf. This matters for policy because internal development fosters complementary demand for managers who can redesign processes, as well as for workers who can effectively utilize data at the point of decision. Suppose we promote software investment and productivity together. In that case, the benefits lie not only in the increased code but also in its improved application, as measured by the time saved, reduced errors, and timely delivery of services. This stress on the potential benefits of software investment and productivity will make stakeholders feel optimistic and supportive of these initiatives.

Culture, time rules, and the returns to software investment and productivity

Work culture influences how quickly software yields results. Europe’s Working Time Directive limits average weekly hours to 48 and guarantees at least four weeks of paid annual leave. In contrast, the United States lacks a federal law mandating paid vacation; time off largely depends on individual company policies or state regulations. These institutional choices impact the speed of responses, coordination across time zones, and the pace of iteration in digital projects. They also affect diffusion: if a system allows more asynchronous work but slows down cross-team decision-making, the benefits of real-time tools may diminish. The point is not that Europe should extend working hours—the evidence on hours and output is mixed—but that its institutions must increase the productivity of each hour by streamlining decision-making, reducing administrative delays, and enhancing management capabilities within humane time constraints.

Two more facts support this argument. First, Europeans tend to work fewer hours. For example, Germans worked around 1,331 hours in 2023, while Americans worked significantly more, depending on the source. However, differences in productivity per hour remain the main factor behind income disparities. Second, management quality varies in meaningful ways. The World Management Survey and similar studies rank the U.S., UK, Sweden, and Canada at the top, with Germany next, and less effective management practices are found in Southern Europe. Better-managed schools, hospitals, and factories are more productive, adopt digital tools more quickly, and achieve better outcomes. In simulations and recent cross-country analyses, management practices account for a significant portion of productivity gaps with the U.S. In other words, the value of the same working hour can vary depending on how management, skills, and software come together.

What should educators and policymakers do to raise software investment and productivity?

Education offers Europe the quickest route to closing the gap since schools, colleges, and governments shape the factors that make software valuable: skills, data, and management. Start with basic digital skills. In 2023, only 56% of EU citizens possessed at least basic digital skills; the EU’s Digital Decade goal is to reach 80% by 2030. This shortfall is significant. It limits the extent to which new software can enhance output in public services and small businesses. The most immediate solution is focused adult learning that enhances adaptive problem-solving skills—the modern skill measured by PIAAC. Countries that excel at adaptive problem-solving also effectively use digital tools. The U.S. has its own weaknesses in this area, as about one-third of adults score at or below Level 1 in adaptive problem-solving. The goal is not to mimic a model, but to excel in the areas where Europe values most: universal skills.

Next, we should build management capacity in education, just as we do in STEM fields. Evidence from the World Management Survey in high schools shows that strong leadership and effective operations lead to increased achievement. Practically, this means selecting and training school leaders in the same manner as we train hospital principals, with specific targets, measurements, and guidance on process improvement, data utilization, and team feedback. In the public sector, even small changes can make a difference. A ministry that clearly defines decision-making responsibilities for IT, procurement, and data governance will experience quicker cycles from pilot programs to wider implementation. This is how software investment and productivity can advance together—by removing obstacles and ensuring staff possess the skills needed to adopt tools quickly.

Third, improve procurement and system reliability. Europe is good at protecting workers; now it must ensure reliability. Shift from one-time projects to pay-for-performance contracts that reward verified uptime for digital systems in schools and universities, and that fund training linked to measurable reductions in administrative time. ECIPE’s policy brief calls for an increase in R&D and intangible investments. Education agencies should translate this into long-term contracts for software as a service, data pipelines with open standards, and shared services for payroll, admissions, and student support. The test is straightforward: can a school open a class, hire a substitute, or process a grant without a lengthy email chain? If not, the system has capital but lacks complementary components.

Fourth, promote asynchronous collaboration across time zones without increasing overall hours. Europe’s time regulations reflect social choices. Keep them. But adjust how and when hours are used by implementing default asynchronous workflows in research and administration, such as shared documents with version control, decision logs, four-hour response times for critical tasks, and guidelines to reduce “dead time.” These organizational practices can enhance the effectiveness of coding efforts. They fit within a human-centered approach and lead to improvements in software investment and productivity, resulting in fewer delays for students and researchers.

Finally, prioritize key measurements. Each education ministry and major university should publish two annual indicators: software capital per worker (including internally developed software) and management quality (using adapted WMS-style tools for schools and agencies). Pair these metrics with results on adaptive problem-solving from adult learning programs aligned with teacher training and administrative staff development. If these three indicators rise together, you are building the necessary complements; if they do not, you are merely purchasing licenses, not achieving productivity gains.

Anticipating the critiques

One critique argues that hours, not software, drive the gap. However, evidence suggests that productivity per hour—measured by TFP and value added—is the critical factor. Another claim suggests that Europe’s social model cannot support rapid iteration. Yet, while the Working Time Directive limits hours, it does not prohibit speed; it encourages institutions to use organization and management to maximize hourly productivity. A third argument posits that the measurement of organizational capital is too inconsistent to inform policy. That is precisely why we should make software investment, which can be tracked through budgets and accounts like BEA or EU-KLEMS, visible. It’s also vital to monitor management quality using clear criteria. Finally, a critique warns that pushing for software might exacerbate inequality if skills fail to keep pace with it. This concern is valid, and it highlights the necessity: without a boost in basic digital skills and adaptive problem-solving, the benefits of software will concentrate in a few institutions. The policy response should not be to slow down software improvements; it should be to enhance skills and management quality to ensure that software gains are widely distributed.

The key contrast is straightforward: France allocates 2.4% of its GDP to software, compared to Germany’s 0.7%, while Germany reports a much greater level of organizational capital. We can debate the balance endlessly, or we can recognize the complement: software investment and productivity rise when code meets skills, effective management, and rules that facilitate quick decision-making. Europe’s social model is not the barrier; the actual obstacle is the friction that hampers the returns on investment in software. The solution is practical and achievable: invest in measurable software, enhance trainable management capacity, boost basic digital skills, and redesign workflows so that protected time translates into productivity rather than idleness. If Europe takes these steps, it can maintain its human touch while strengthening its economic foundation. The productivity gap will decrease not because people work longer hours, but because every hour that is protected will yield more learning, research, and value—all of which will be visible in classrooms, labs, and financial records.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bessen, J. (2024). The Intangible Divide (AEA 2025 program paper). Evidence on software investment measures and own-account software.

Bureau of Economic Analysis (via Richmond Fed). (2024). Intellectual property products accounted for ~31% of private fixed investment and 5.5% of GDP in Q1-2024.

ECIPE. (2024). Keeping Up with the US: Why Europe’s Productivity Is Falling Behind. Policy brief on intangibles, ICT investment, and TFP links.

Eurostat. (2023–2024). Digital skills indicators: 56% of EU citizens with at least basic digital skills (2023); Digital Decade targets.

FRED/BEA. (2024). Private fixed investment—Software (custom and own-account), annual series through 2023.

OECD/PIAAC. (2024–2025). Survey of Adult Skills 2023 results and U.S. country note (adaptive problem-solving levels).

OECD/WMS & related research. (2021–2025). Management practices explain a sizable share of cross-country productivity gaps; school and hospital management findings.

VoxEU/CEPR. (2025). Intangible capital in France and Germany: software ≈2.4% vs 0.7% of GDP; organisational capital ≈2.5× larger in Germany; implications for accounting.

Washington Post. (2024). Germany’s annual hours worked around 1,331 (OECD).

European Commission—Employment. (n.d.). Working Time Directive (2003/88/EC): 48-hour average cap; ≥4 weeks paid leave. U.S. DOL—No federal mandate for paid vacation.