Financial Education in the Digital Age: Help People Earn the Market, Not Chase Alpha

Input

Modified

Retail investing is up; teach people to earn the market, not chase alpha. Use low fees, diversification, and cool-off safeguards to curb herding and fraud—especially for seniors Tie curricula to app defaults so good habits are automatic and long-term wealth compounds

One number tells the story: 18%. That is the share of U.S. equity trading now attributed to retail investors, roughly double the historical norm, thanks to zero-commission apps, always-on feeds, and financial education in the digital age. The shift is fundamental. Retail's market share has remained around this new level for three straight years, even as total volumes reached record levels in 2024. The phone in our pocket is the gateway to a world of possibilities. 91% of U.S. adults own a smartphone, and among those aged 65 and older, smartphone adoption is now nearly four in five. A mass migration into public markets has already happened. The debate is about what we teach people to do once they arrive. If our goal is to help households beat the pros, we will fail. Instead, we design education and guidelines that enable people to earn market returns, which is the average return of the market, minus small costs, and avoid significant mistakes. In that case, we can increase lifetime wealth while keeping risks manageable.

We are changing the usual pitch for investing classes. The old approach says that if you learn the correct ratios and read the right charts, you can outsmart the market. That is not the right goal. Even professional managers rarely beat broad indexes over long periods when you factor in fees and taxes. The advantages they maintain—scale, deep research, and disciplined processes—do not disappear just because retail investors have cheaper phones and faster apps. What digital access does change significantly is participation and behavior. Many more people can now own stocks at very low costs, with instant execution and constant information. The question is not whether the average retiree can out-trade a hedge fund. The question is whether we can transform cheaper access and financial education in the digital age into safer habits that yield market returns, reduce avoidable losses, and resist viral trends.

The evidence for this new approach is strong. The arithmetic behind index funds has only become more convincing. In 2024, the average expense ratio for U.S. equity index ETFs dropped to 0.14%, with similar fee reductions across Europe as providers compete with one another. Over extended periods, SPIVA scorecards continue to show that most actively managed equity funds underperform their benchmarks after fees. Education that starts with these facts—getting the market cheaply, avoiding complicated high-fee products, rebalancing, and minimizing taxes—puts us halfway to success. Teaching people to outperform full-time professionals is not just unrealistic; it also distracts from the few actions that reliably build wealth.

Financial education in the digital age means lower costs and higher responsibility

Digital access has removed three classic barriers: trading costs, information costs, and market access. This change is not just theoretical. The early internet already increased participation among connected households. Using panel data from the 1990s, Bogan (Cornell) found that households with computers were significantly more likely to start owning stocks; this effect was comparable to an increase of approximately $27,000 in household income or 2.5 more years of schooling. The same logic applies today with smartphones and zero-commission brokers. In the U.S., retail now accounts for about 18% of equity volume; in Europe, where on-exchange retail activity is smaller (around 14%), exchanges and regulators are actively promoting stronger literacy and access to deepen capital markets. Lower costs have expanded the audience; this expansion benefits everyone, empowering them to take control of their financial future, depending on how we design learning and the guidelines around it.

The demographic story matters. The new retail group is not just comprised of young day traders; older adults are also getting online. Seventy-nine % of Americans aged 65 and older now own a smartphone, and dependence on smartphones for internet access among seniors has more than doubled since 2019. This trend is both empowering and risky. Fraud losses reported by older adults to U.S. authorities have increased significantly since 2020, particularly for high-dollar scams. Teaching seniors to invest without recognizing this threat is irresponsible. Digital literacy modules must cover app permissions, identity verification, and how scammers exploit the use of urgency and trust to deceive users. Brokerages should implement additional safety measures for seniors, such as enhanced verification procedures for withdrawals and new assets, while also offering a "trusted contact" option during account creation. These minor adjustments are not about being controlling; they prevent significant mistakes that no amount of textbook theory can fix, providing a sense of security and protection to the audience.

Herding is another design challenge. Studies from various crises, including the 2008 financial crisis and the pandemic, demonstrate that copycat behavior amplifies volatility, particularly in noisy environments where incentives encourage rapid buying. The EU's market regulator has warned that tips from social media can influence prices temporarily, but do not provide a lasting edge; the long-term benefits are an illusion. Our curricula should treat virality as a risk factor. The more widely an idea spreads, the stricter your checklist should be before taking action. This rule should also be integrated into apps. Suppose a user attempts to buy a stock that has spiked due to social media mentions or surged significantly in a short period. In that case, the app should display a "cool-off" panel showing the variation in analyst forecasts, trends in free cash flow, and alternatives with lower risk, such as a broader sector ETF. Education and product design should go hand in hand.

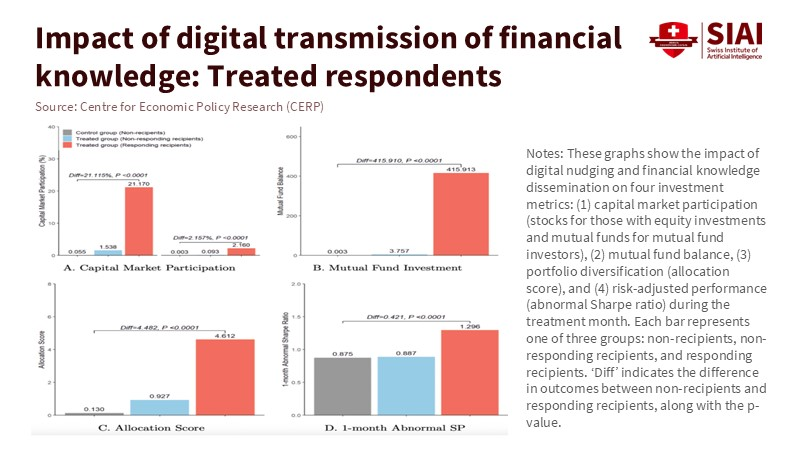

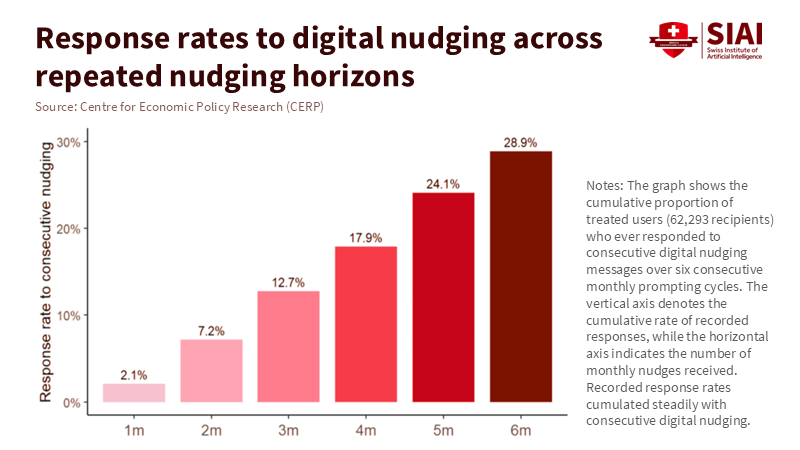

Digital nudging and sustained participation

So what should educators and administrators teach? First, set a humble and measurable target: "Market return minus small costs," not "alpha." This approach helps the audience to stay focused and goal-oriented. Start with the fee table. Typical investors can now hold global equity exposure for 0.10–0.20% per year. Show how a 1-point fee difference can add up to tens of thousands of dollars over 25 years. Then practice the three key factors that most explain differences among self-directed investors: contributions, diversification, and behavior during downturns. Turn vague advice into checklists: minimum savings rates by life decade, the "90/10 rule" for asset allocation, a simple rebalancing calendar, and a pre-commitment script for bear markets. The goal is not novelty but repeatability.

Second, consider incorporating digital habits into the curriculum. Many investors now trade during pre-market hours or buy low-priced stocks because it is easy on screens. Data shows that these options often come with wider spreads and higher costs. An "Investing 101" class that never mentions spreads, order routing, and after-hours liquidity misses how people really lose money. Educators should simulate real order tickets—limit versus market orders, time-in-force, and lot sizing—and demonstrate the costs involved when habits are incorrect. This is not just advanced knowledge; it is essential for achieving market returns.

Third, connect education to defaults that help people make the right choices automatically. If a school, union, or municipality offers a learning module, pair completion with a simple setup: a diversified target-date or risk-based portfolio, dividend reinvestment turned on, a specific tax-lot method pre-selected, and a once-a-year rebalance reminder. Set the watchlist to display funds first, followed by single stocks. This is like a safety belt for investing. For working adults who want to learn more, consider adding a short extra module on themes and individual stock analysis, but set limits on this extra part by default. The consistent message is that education is more about building good routines than rare insights.

A common criticism says, "If individuals just end up in low-fee index funds, why teach them at all?" Because the path to that goal is filled with traps, and confidence matters. The latest national study from the FINRA Foundation reveals that financial knowledge remains stagnant, self-reported satisfaction is lower, and persistent gaps persist based on income and education. However, the same data indicates that confidence can improve when people practice with realistic tools. Short, focused modules that target the few decisions retail investors regularly make—such as automating contributions, selecting low-cost funds, and disregarding hype—can yield significant benefits compared to their modest teaching costs. A further policy rationale comes from Europe: participation is a public good when capital markets are limited. The EU is exploring ways to enhance the participation of households in markets while mitigating associated risks. Education is a tool that can scale faster than income growth or tax breaks.

What about the claim that individual investors, once trained, might still underperform due to churn? That is possible—and fixable. Broker designs that obscure total trading costs or promote quick trades exacerbate the issue. Regulators are starting to respond (for example, the U.K.'s Consumer Duty and EU consultations on the retail investor experience); however, educators can also play a role by teaching personal "T-accounts." Every trade should identify its edge, alternatives, costs, and exit strategy. If you cannot fill in the T-account in 30 seconds, you shouldn't trade. This practice reduces turnover to the few decisions where you genuinely have a strategy. It also helps make education a habit rather than just a one-time seminar.

A second critique raises the concern that bringing new investors into markets at high valuations can lead to disappointment. This concern is valid, but it suggests a process rather than abstaining. If contributions are regular, assets are diversified globally, fees are as low as possible, and behavior guidelines are followed, the entry price becomes less significant over the long term. The correct comparison is not "Did you outperform a popular manager this year?" but "Did you capture the equity risk premium without giving most of it away?" Education that instills this standard may seem dull on YouTube, but it will lead to excellent outcomes in retirement accounts.

Finally, we need to be honest about the question of an "elderly migration." Will tech-savvy retirees abandon advisors en masse? Probably not. Many will choose a mix: a low-fee core they manage themselves, along with occasional professional advice for taxes, estate planning, and longevity risks. That is healthy. Where we should not compromise is on transparency. Seniors who seek advice should be able to see, in one place, the all-in fee in dollars and the low-cost index alternative they might be missing. That single comparison—let's call it the "quiet benchmark"—does more to protect savings than any catchy phrase about sophistication.

Financial education in the digital age must promise confidence

The offer we extend to citizens should be clear and straightforward. We will teach you enough to hold the market cheaply, avoid viral traps, and maintain your plan during tough times. Your app will guide you toward choices that limit avoidable mistakes. If you want to go beyond the basics, we will help you understand how to assess that risk and what it entails in terms of cost. In return, we will not pretend you can out-research teams with PhDs and access to alternative data, nor will we shame you for wanting a human advisor for some parts of your journey. The measure of success should be your after-fee, after-tax wealth and your ability to sleep well at night—not a leaderboard.

This approach can grow. Falling fees and intense competition among providers have made broad, diversified investments more affordable each year. Exchanges and regulators are learning from the meme-stock experience and beginning to curb harmful patterns. The research shows that when costs decrease, participation increases. The primary challenge now is education and user experience. If schools, employers, and municipalities teach timely modules that connect to key life events—such as a person's first job, first rollover, or first taxable account—and if product teams align defaults with the curriculum, we can transform millions of new accounts into lasting wealth.

Return to the 18% we started with. That number is not a guarantee of excess returns; it is a reminder of responsibility. Financial education in the digital age should not create amateur day-traders. It should develop informed owners of the economy who earn what the markets offer and dodge the unnecessary pitfalls of speed and hype. We will know we are succeeding when the typical investor can easily summarize their plan in one sentence, show their total cost on one line, and ignore a thousand shiny distractions. Teach that, and the benefits will build quietly—for decades.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bogan, V. (2006). Stock Market Participation and the Internet. Cornell University, Dyson School Working Paper WP 2006-10. Cornell_Dyson_wp0610

European Securities and Markets Authority (2024). Report on Trends, Risks and Vulnerabilities No. 2, 2024. ESMA/50-524821-3444.

Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (2025). National Financial Capability Study (2024 wave) – Key Findings.

Investment Company Institute (2024). 2024 Investment Company Fact Book.

Investment Company Institute (2025). Trends in the Expenses and Fees of Funds.

OECD/INFE (2023). International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy.

Pew Research Center (2024). Americans' Use of Mobile Technology and Home Broadband.

Reuters (2024). "No link between social media stock tips and big returns in long run, says EU watchdog."

SIFMA (2024). U.S. Equity Market Structure Compendium.

SPDJI (2025). SPIVA U.S. Scorecard, Year-End 2024.

U.S. Federal Trade Commission (2025). Data Spotlight: Impersonation Scams and Older Adults.

VoxEU/CEPR (2025). "Stock market participation and financial education in the digital age."

Vanguard fee updates reported in: Financial Times (2025), "Vanguard cuts fees on European equity funds as competition mounts."

Cboe retail participation and EU context: Reuters (2024), "Exchange operator Cboe launches push to attract retail investors in Europe."

Cboe/NYSE microstructure notes: Cboe (2024), "U.S. Equities Volume Drivers: Retail Trading in Sub-Dollar Securities."

ACR Journal (2025). "Investor Herding Behaviour During Financial Crises: A Comparative Study."