AI Jobs in Southeast Asia Will Reshape Global Hiring, Not Destroy It

Input

Modified

AI shifts tasks across borders rather than causing mass layoffs Southeast Asia absorbs more of this work thanks to digital capacity and wages Skills, standards, and cross-border partnerships turn the shift into shared gains

We are warned to prepare for a surge. The IMF estimates that artificial intelligence will impact approximately 40 percent of jobs worldwide and around 60 percent in advanced economies. Those numbers sound alarming until we examine what has happened in the labor market since late 2022, when generative AI became popular. A new analysis from Brookings and Yale reveals broad stability in job types, rather than a collapse. The percentage of workers in AI-related jobs has remained stable, and the expected rise in unemployment among the most affected groups has not happened. Simply put, the fuse is long. This is significant because it allows for a gradual shift that is already starting, where task bundles, rather than entire jobs, move across borders. The areas that benefit first are those with rapid digital growth and the most significant wage disparities. The story of AI jobs in Southeast Asia is not just a part of the disruption happening in wealthier regions; it is the focal point, a testament to the region's potential and adaptability in the global AI job market.

AI Jobs in Southeast Asia: Stability Amid the Hype

The best evidence from individual companies shows improvement, not elimination. When over 5,000 customer support agents were equipped with an AI assistant, productivity increased by approximately 14 percent on average, and by more than a third for less experienced workers. This is an important observation: less experienced workers benefited the most, while senior agents experienced the least change. The process is straightforward. AI spreads essential knowledge from top performers to new employees. The takeaway for AI jobs in Southeast Asia is clear. In service sectors where training is more important than formal qualifications, adoption can increase output without immediate layoffs.

Considering the broader perspective, the overall trend remains consistent. The Brookings and Yale study shows no signs of a widespread “AI jobs apocalypse” since the launch of ChatGPT; instead, it reveals stability, along with some early challenges for younger workers. This aligns with how past major technologies have been adopted. Benefits emerge when companies redesign their workflows and invest in complementary systems, rather than introducing a single tool all at once. If displacement occurs gradually, reallocating tasks becomes more significant. Countries that can take on these tasks at scale will benefit first. AI jobs in Southeast Asia act as a pressure release for that migration. However, to ensure sustainable growth and fair practices, collaboration and standards in the AI industry are essential, a responsibility that falls on the shoulders of policymakers.

On the ground, Southeast Asian companies are not just cautiously optimistic about AI; they are also practical in their approach. A new regional survey of over 2,000 manufacturers reveals plans for gradual automation, with most businesses expecting little to no net change—or even growth—in their workforce. This aligns with what executives observe: automate routine tasks, keep people involved, expand services, and move up the value chain. It also reflects the region’s labor landscape. Many “replaceable” jobs typical in advanced economies are less common in those economies. At the same time, customer service, light manufacturing, and digitally deliverable tasks continue to grow.

AI Jobs in Southeast Asia and the New Offshoring Wave

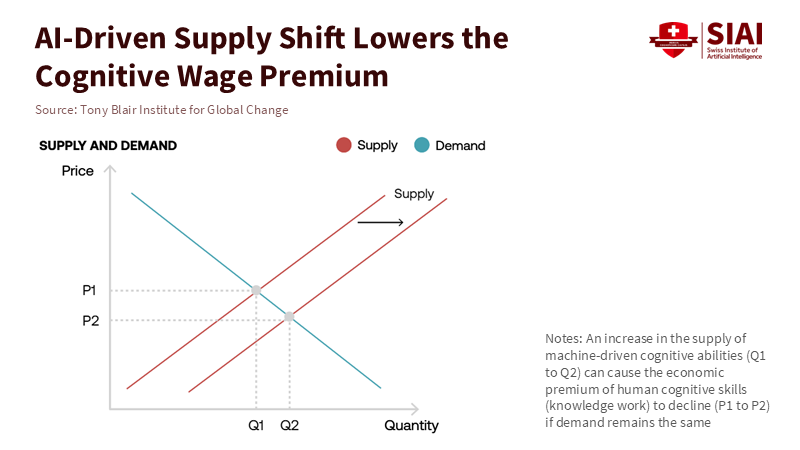

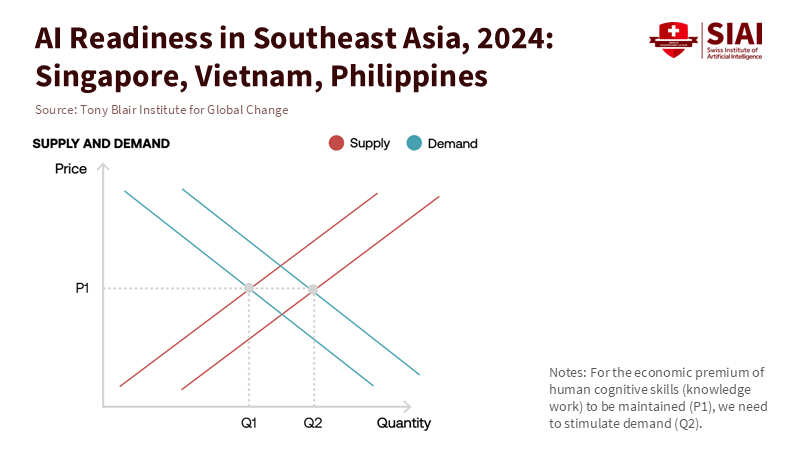

Here is the pivot that matters for policy. The IMF’s global mapping indicates that a smaller share of jobs in emerging markets is highly exposed compared to advanced economies, since cognitive-intensive roles are more concentrated there. This disparity interacts with remote work enabled by platforms. As companies in wealthier countries bundle knowledge work, they can shift increasing amounts of work to lower-cost, digitally equipped hubs. AI jobs in Southeast Asia are a natural fit for these tasks because the region combines skilled talent with competitive wages and increasing AI capabilities.

The numbers already reflect this shift. Southeast Asia’s digital economy experienced double-digit growth in 2024, with a gross merchandise value of approximately US$263 billion, revenues of around US$89 billion, and profits of close to US$11 billion. These figures are operational results that support hiring in e-commerce, payments, logistics technology, and customer support. As digital companies grow, they purchase more cloud services, implement more AI tools, and contract for services such as content creation and analytics, often on a regional basis. This growth holds promise for a promising future in Southeast Asia.

Business processes and IT services illustrate this point. The Philippine IT-BPM sector concluded 2024 with approximately 1.82 million jobs and US$38 billion in revenue, anticipating further growth this year. Industry roadmaps now aim for over two million jobs by mid-decade. This is occurring alongside widespread AI adoption rather than despite it. The reason for this is complementarity: automation handles routine tasks while human teams ensure quality and manage relationships. Vietnam tells a similar story with its high-tech sector, where FPT’s growing AI investments and export increases highlight a shift toward higher-value, AI-enabled services for global clients. AI jobs in Southeast Asia are not just forecasts; they represent actual employment opportunities.

Digitally delivered services serve as a bridge between traditional and digital services. ASEAN’s push for a Digital Economy Framework Agreement and new digital trade deals, such as the EU-Singapore Free Trade Agreement, reduces obstacles to cross-border data and services. When data flows freely and contracts are easily completed, small teams in Kuala Lumpur or Cebu can connect with corporate operations in Frankfurt or Seattle. Trade data and policy reports indicate rapid growth in digitally deliverable exports across Asia-Pacific over the last decade, outpacing goods by a wide margin. AI speeds up this trend by standardizing and breaking down tasks, making them easier to transfer.

Two additional points shift the narrative away from doom. First, where AI skills are in high demand, wages tend to increase. PwC’s 2025 Global AI Jobs Barometer reveals a significant wage premium for positions requiring AI skills, with a faster rise in those job postings even as total postings decline. Second, the most thorough field studies demonstrate that augmentation enhances productivity and quality in services, rather than replacing people completely. Both trends benefit ecosystems that can train quickly and match talent to global needs. This is precisely where AI jobs in Southeast Asia excel.

AI Jobs in Southeast Asia: What Educators and Policymakers Must Do

Suppose advanced economies experience slower net job creation as entry-level knowledge tasks are moved offshore. In that case, the policy response cannot be to resist change. The right approach is to focus on complementary skills at home while enabling responsible cross-border services that boost global productivity. For Southeast Asia, the strategy should be to establish a framework for ongoing mobility, including reliable power and connectivity, consistent data rules, cloud service credits for small businesses, and micro-credentials that align with genuine task bundles in global workflows. The region already has momentum. Six of ten ASEAN economies now have national AI strategies, and international companies are investing throughout the area—from Microsoft’s investments in Indonesia to Vietnam’s AI centers. The opportunity is there; it now needs institutional support.

Education systems must shift from one-time credentials to stackable proof of ability. The practical unit should be the task, not the course. A content associate in Ho Chi Minh City should be able to demonstrate proficiency in retrieval-augmented writing for compliance or in creating evaluation sets for multilingual chatbots. Community colleges and polytechnics can lead by teaching “workflow literacy”: prompt chains, data management, escalation thresholds, and human-in-the-loop design. Teacher training should follow the same principles, using classroom-friendly AI tools to create rubrics, provide feedback, and run simulations. The goal is not to chase tools but to develop judgment on how and when to apply them. This is how AI jobs in Southeast Asia can continue to create value instead of devaluing labor.

From pilots to policy—a playbook for shared gains

Hiring pipelines must expand quickly, but quality must also improve with growth. Ministries can co-fund apprenticeships with export-focused companies, combine paid training with micro-credentials, and support these with outcome-based vouchers. Where local curricula fall short, import them. Singapore’s experience shows that even high-skill jobs can be offshored when they become modular and can be performed remotely. To counter this, invest in areas that are difficult to move offshore, such as data governance, safety evaluation, model oversight, and sector-specific AI where user proximity is crucial. The aim is to create a regional division of labor where routine tasks are automated, modular tasks flow across borders, and in-depth, high-judgment work is done locally.

Labor protections must also evolve. As more work moves through platforms and across borders, enforceable standards on pay, safety, data rights, and dispute resolution are critical. The Brookings and Yale team is correct that we need better usage and labor data from major AI companies to spot real disruptions early. Regulators in the region should demand privacy-focused data from enterprise AI applications, allowing us to determine whether augmentation is replacing automation and identify areas where retraining is urgently needed. Transparency is crucial: it manages hype and ensures timely support. AI jobs in Southeast Asia can thrive if workers see clear pathways, not just temporary gigs.

Method notes are essential because the data can be inconsistent. When we say net job creation appears stronger in Southeast Asia than in advanced economies for AI-exposed jobs, we combine information from various sources rather than depending on a single dataset. We use BPO and IT-BPM employment and revenue as indicators of demand for exportable services. We link this with trade data for digitally delivered services and investments by companies that expand local AI capacity. We verify the lack of mass layoffs with the Brookings and Yale analysis of job types. Each source has its limitations, but collectively, they indicate a measurable and accelerating trend: the reallocation of tasks to AI jobs in Southeast Asia is underway.

Critics might argue that offshoring merely postpones problems, suggesting that automation will eventually eliminate these jobs. This viewpoint overlooks two key aspects of service work. First, quality can vary and is challenging to encode. AI raises the median quality but struggles with complex cases that humans can resolve through context and understanding. Second, trust and local knowledge become increasingly valuable as services become more complicated. As firms bundle more sophisticated workflows—such as risk assessment, compliance, and sales engineering—the human element becomes increasingly important, not less so. Evidence so far supports this claim: productivity gains from augmentation are significant, while overall displacement remains limited and inconsistent. Suppose we guide adoption towards human-centered design and connect benefits to uptime, safety, and customer satisfaction. In that case, economic logic favors creating more higher-quality jobs rather than fewer jobs.

The final challenge is speed. Companies desire immediate savings; augmentation requires skill. Policy can change incentives. Procurement regulations can prioritize results over workforce reductions. Export credit agencies can support contracts that include retraining commitments in both the purchasing and selling countries. Tax policies can encourage investment in complementary assets, such as data quality, governance, and training platforms, that enhance speed and safety. With these guardrails in place, AI jobs in Southeast Asia can become a positive story: increased productivity for clients, rising wages for skilled workers, and a stronger regional position in the global services sector.

The fuse is long; make the most of it. The headline statistic remains valid: AI is expected to impact 40 percent of jobs worldwide and 60 percent in advanced economies. However, exposure does not dictate outcomes. Current evidence suggests stability in the labor market and significant gains from augmentation. During this transition period, tasks are moving. They are moving to regions capable of absorbing and enhancing them. AI jobs in Southeast Asia are positioned at this intersection of capability, cost, and policy. Suppose advanced economies prepare for cooperation at home and abroad. In that case, they will replace the illusion of self-sufficient automation with a stronger reality: resilient services, shared productivity, and greater opportunity. If Southeast Asia focuses on skills, standards, and data-driven governance, it will not just catch work that shifts from elsewhere; it will establish a new foundation in the global economy, supported by human judgment enhanced by technology. The fuse is long. Use it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bain & Company; Google; Temasek (2024). economy SEA 2024 (GMV, revenue, profit highlights).

Brookings Institution; Budget Lab at Yale (2025, Oct. 1). New data show no AI jobs apocalypse—for now.

FPT (2024–2025). AI center investment and AI factory partnership with NVIDIA; revenue updates. Reuters coverage and company releases.

International Monetary Fund (2024, Jan. 14). Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work (Staff Discussion Note); blog summary by K. Georgieva.

IBPAP (2025, Jan. 15). Philippine IT-BPM industry caps 2024 with 1.82 m jobs and US$38 bn revenue; corroborated by Reuters (2024, Oct. 2).

PwC (2025, Jun. 26). Global AI Jobs Barometer 2025 (wage premium and postings growth).

Tony Blair Institute & Institute for Adult Learning (2025, Jul. 24). Augmenting Intelligence: Shaping the Future of Work in Southeast Asia (AI strategies; digital offshoring risk).

World Economic Forum & EU reporting (2024–2025). Digital trade agreements; ASEAN digital economy integration (EU–Singapore digital trade agreement; ASEAN DEFA progress).

Yahya, F. (2025, Oct. 2). Southeast Asia optimistically embraces digital automation. East Asia Forum (regional survey on planned automation; net employment expectations).

Yale Budget Lab (2025, Oct.). Evaluating the Impact of AI on the Labor Market (underpinning dataset and methodology).

Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D., & Raymond, L. (2025). Generative AI at Work (QJE / NBER): 14–15% productivity gains; largest for novices.