AI Writing Education: Stop Policing, Start Teaching

Published

Modified

Students already use AI for writing; literacy must mean transparent, auditable reasoning Redesign assessment to grade process—sources, prompts, and brief oral defenses—alongside product Skip detection arms races; provide approved tools, disclosure norms, and teacher training for equity

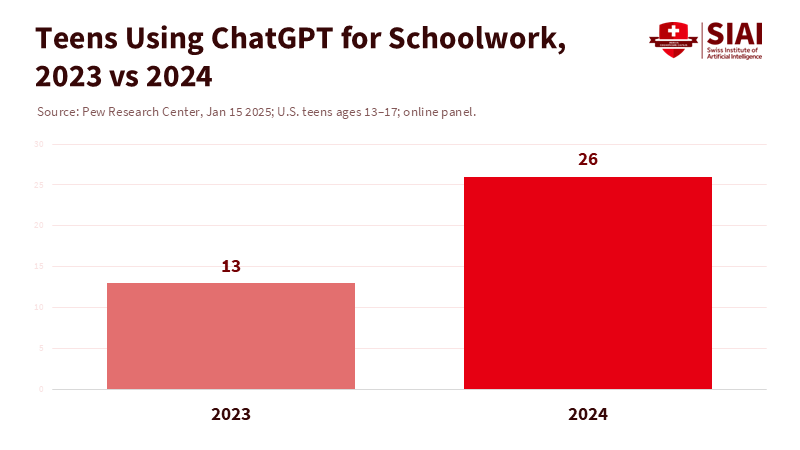

One number should change the discussion: the percentage of U.S. teens who say they use ChatGPT for schoolwork has doubled in a year—from 13% to 26%. This isn’t hype; it’s the new reality for students. The increase spans all grades and backgrounds. It highlights a simple truth in classrooms: writing is now primarily a collaboration between humans and machines, rather than a solo task. If AI writing education overlooks this change, we will continue to penalize students for using tools they will rely on in their careers, while rewarding those who conceal their use of these tools. The real question is not whether AI belongs in writing classes, but what students need to learn to do with it. They must know how to create arguments, verify information, track sources, and produce drafts that can withstand scrutiny. These skills are central to effective writing in the age of AI.

AI writing education is literacy, not policing

The old approach saw writing as a private battle between a student and a blank page. This made sense when jobs required drafting alone. It makes less sense now that most writing—emails, briefs, reports, policy notes—is created using software that helps with structure, tone, and wording. The key skill is not polishing sentences but showing and defending reasoning. Therefore, AI writing education should redefine literacy as the ability to turn a question into a defendable claim, collect and review sources, collaborate on a draft with an assistant, and explain the reasoning orally. This means shifting time away from grammar exercises to “argument design,” including working with claims, evidence, and warrants, structured note-taking, and short oral defenses. Students should learn to use models for efficiency while keeping the human element focused on evidence, ethics, and audience considerations.

Institutions are starting to recognize this shift. Global guidance emphasizes a human-centered approach, prioritizing the protection of privacy, establishing age-appropriate guidelines, and investing in staff development rather than advocating for bans. This guidance is not only necessary but also urgent. Many countries still lack clear rules for classroom use, and most schools have not validated tools for teaching or ethics. A practical framework emerges from this reality: utilize AI while keeping the thinking clear. Require students to submit a portfolio that includes prompts, drafts, notes, and citations along with the final product. Assess the reasoning process, not just the final output. When students demonstrate their inputs and choices, teachers can evaluate learning rather than just writing quality. The outcome is a clearer, fairer standard that reflects professional practices.

From essays to evidence: redesigning assignments

If assessments reward concealed work, students will hide the tools they use. If they value clear reasoning, they will show their steps. AI writing education should revamp assignments to focus on verifiable evidence and clear, concise language. Replace standard five-paragraph prompts with relevant questions tied to recent data: analyze a local budget entry, compare two policy briefs, replicate an argument with new sources, and defend a suggestion in a three-minute presentation. For each task, require a “transparency ledger”: the prompt used, which sections were AI-assisted, links to all sources, and a 100-word methodology note explaining how those sources were verified. The ledger evaluates the process while the paper assesses the result. Together, they promote transparency and make integrity a teachable lesson. This approach empowers students to take responsibility for their evidence, fostering a sense of control and accountability. This addresses the temptation to outsource thinking while allowing students to utilize AI to draft, summarize, and revise their work.

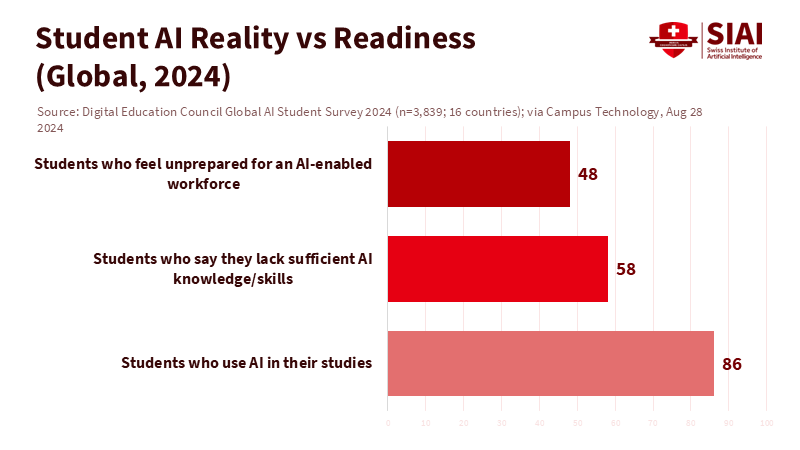

Methodology notes are essential. They can be brief but must be genuine. A credible note might say: “I used an assistant to create an outline, then wrote paragraphs 2–4 with help on structure and tone. I checked statistics against the cited source—Pew or OECD—not a blog. I verified claims using a second database and corrected two discrepancies.” The goal is not to turn teachers into detectives; it is to empower students to take responsibility for their evidence. Surveys indicate that students want this. A 2024 global poll of 3,839 university students across 16 countries found that 86% already use AI in their studies; yet, 58% feel they lack sufficient knowledge of AI, and 48% do not feel ready for an AI-driven workplace. This gap represents the curriculum. Teach verification, disclosure, and context-appropriate tone—and assess them.

Fairness, privacy, and the detection fallacy

Schools that rely on detection tools to combat AI misuse often overlook the broader lesson and may inadvertently harm students. Even developers acknowledge the limitations. OpenAI shut down its text classifier due to low accuracy. Major universities and teaching units advise against using detectors in a punitive way. Turnitin now avoids scoring below 20% on its AI indicator to prevent false positives. Media reports on technology and education have shown that over-reliance on detectors can disadvantage careful writers—the very students we want to reward—because polished writing can be misinterpreted as machine-generated. The trend is clear. Detection can serve as a weak indication in a discussion, not conclusive proof. Policy should reflect this reality.

There is also a due-process issue. When detection becomes punitive, schools create legal and ethical risks. Recent legal cases demonstrate the consequences of vague policies, opaque tools, and students being punished without clear rules or reliable evidence. This leads to distrust among faculty, students, and administrators, creating a need for mediation on a case-by-case basis. A more straightforward path is to establish a policy: detections alone should not justify penalties; evidence must include process artifacts and source verifications. Students need to understand how to disclose assistance and what constitutes misconduct. Additionally, institutions should adhere to global guidance emphasizing transparency, privacy, and age-appropriate use, as the questions of who accesses student data, how it is stored, and how long it is retained do not disappear when a vendor is involved.

Building capacity and equity in AI writing education

Policy alone without training is not effective. Teachers require time and support to learn how to create prompts, verify sources, and assess process artifacts. Systems that already struggle to recruit and retain teachers must also enhance their skills. This is a critical investment, not an optional extra. Educational policy roadmaps highlight the dual challenge: we need sufficient teachers, and those teachers must possess the necessary skills for new responsibilities. This includes guiding students through AI-assisted writing processes and providing feedback on reasoning, not just on the final product. Professional development should focus on two actions that any teacher can implement now: first, model verification in class with a live example; second, conduct short oral defenses that require students to explain a claim, a statistic, and their choice of source. These practices reduce misuse because they reward independent thinking over copying.

Equity must be a priority. If AI becomes a paid advantage, we will further widen the gaps based on income and language. Schools should provide approved AI tools instead of forcing students to seek their own. They should establish clear guidelines for disclosure to protect non-native speakers who use AI for grammar support and fear being misunderstood. Schools should also teach “compute budgeting”: when to use AI for brainstorming, when to slow down and read, and when to write by hand for retention or assessment. None of this means giving up on writing practice; it means focusing on it. Maintain human-only writing for tasks that develop durable skills, such as note-taking, outlining, in-class analysis, and short reflections. Use hybrid writing for tasks where speed, searchability, and translation are crucial. This way, students gain experience with both approaches, as well as with knowing when to question machine outputs. The result is a solid standard: transparent, auditable work that any reader or regulator can trace from claim to source. Evidence suggests that students are already utilizing AI extensively but often feel unprepared. Addressing this gap is the fairest and most realistic way forward.

The figure that opened this piece—26% of teens using ChatGPT for schoolwork, up from 13%—should not alarm us. It should motivate us. AI writing education can raise standards by clarifying thought processes and enhancing the quality of writing. We can teach students how to form arguments, verify facts, and provide assistance. We can resist the temptation of detection tools while maintaining integrity by assessing both the process and the end product. We can protect privacy, support teachers, and bridge gaps by providing approved tools and clear guidelines. The alternative is to continue pretending that writing a blank page is the standard, and then punishing students for engaging with the realities of the world we have created. The choice is straightforward. Build classrooms where evidence matters more than eloquence, transparency is preferred over suspicion, and reasoning triumphs over gaming the system. This is how we prepare writing for the future—not by banning change, but by teaching the skills that make using change safe.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Campus Technology. (2024, August 28). Survey: 86% of students already use AI in their studies.

Computer Weekly. (2025, September 18). The challenges posed by AI tools in education.

OpenAI. (2023, July 20). New AI classifier for indicating AI-written text [update: classifier discontinued for low accuracy].

OECD. (2024, November 25). Education Policy Outlook 2024.

Pew Research Center. (2025, January 15). Share of teens using ChatGPT for schoolwork doubled from 2023 to 2024.

UNESCO. (2023; updated 2025). Guidance for generative AI in education and research.

Turnitin. (2025, August 28). AI writing detection in the enhanced Similarity Report [guidance on thresholds and false positives].

The Associated Press. (2025). Parents of Massachusetts high schooler disciplined for using AI sue school.