Stop the Wiring: How to Contain AI Elder Fraud Without Blaming the Victim

Input

Modified

Older adults lose billions to AI elder fraud each year Biology and deepfake tools amplify impersonation and urgency Add default friction—holds, verification, and reimbursements—to stop wires before money leaves

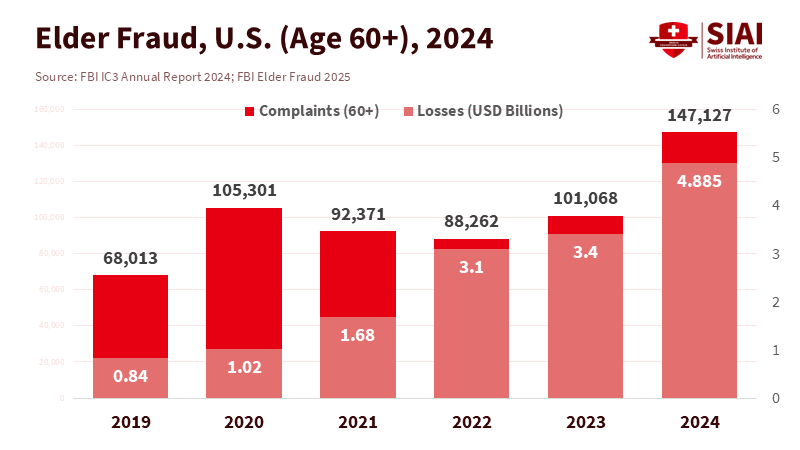

In 2024, Americans reported losing more than $12 billion to fraud. Adults aged 60 and over accounted for a significant portion of this loss. The FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center recorded nearly $4.9 billion in losses from 147,127 older victims, marking a year-over-year increase of over 40 percent. This spike is not random. It corresponds with a new reality in which synthetic voices and polished scripts can mimic a grandchild, a banker, or a government official in seconds. This is AI elder fraud. It takes advantage of how aging brains process risk and social cues, along with a payment system that allows large transfers to leave accounts in minutes. The urgency of the situation cannot be overstated. Improved tips and posters will not solve a structural problem. We need to slow the money, stage the decisions, and create default friction for the highest-risk actions. Otherwise, the losses will continue to grow as the tools become more advanced.

The biology behind AI elder fraud

The uncomfortable truth is also a humane one: aging changes how many of us read faces, evaluate risk, and recognize deceit. Studies indicate that older adults, even those without dementia, are more likely to overlook the “red flags” in untrustworthy expressions and deceptive messages. Neuroscience connects some of this to reduced activity in brain areas that help us detect untrustworthiness. In practice, this means that a warm voice or calm authority carries extra weight, especially when the call feels urgent. That is the aspect that AI elder fraud exploits. A cloned voice that resembles a son in trouble or a bank manager with precise account details is more than just a trick; it is a direct attack on social trust and attention in older individuals. Isolation, grief, or pain further tilts the odds in the scammer’s favor.

We should reject simplistic claims about intelligence “decline.” Evidence points to specific changes that increase vulnerability to scams: slower processing speed, weaker working memory, and a tendency to trust more quickly when cues feel familiar. New research in 2024 and 2025 links phishing vulnerability and susceptibility to scams to these aging-related changes, suggesting that early neurodegenerative issues heighten this risk. This does not make older adults “less capable” overall. It simply makes them prime targets for deception tactics enhanced by machine-generated voices, scripts, and profiles. This is also why education alone is insufficient. The mechanism is biological and social, the attack surface is digital, and the payoff occurs through instant payments. The policy response must address the risk where it truly exists.

Why advice and awareness are not enough

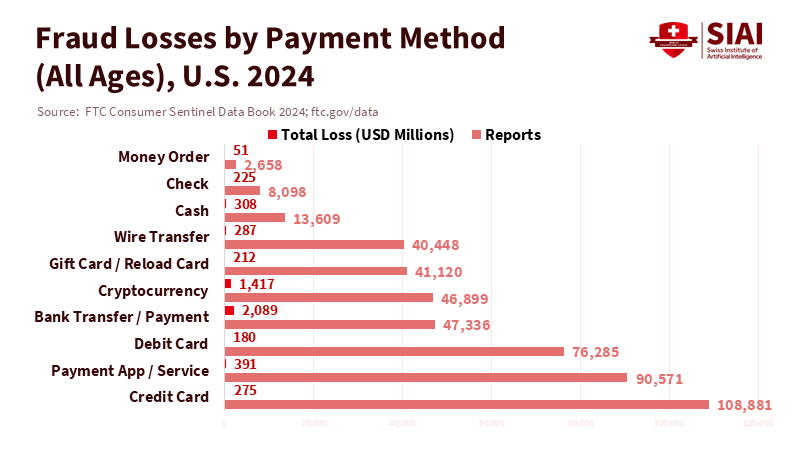

We have advised people to “hang up and call back” for years, yet losses still grew. The FTC’s 2024 data show that total reported fraud losses jumped to over $12 billion, a 25 percent increase from 2023. Median losses for older adults remain higher than for younger groups, and reports of older adults losing $10,000 or more increased more than fourfold from 2020 to 2024. The FBI’s 2024 figures for adults aged 60 and older indicate a surge in both complaints and losses. These numbers highlight the limitations of awareness campaigns when faced with rapidly adapting threats and money movements that occur faster than skepticism can develop. AI elder fraud has lowered the cost of accuracy for criminals, making hesitation more costly for the rest of us.

The impersonation risk is now confirmed at the highest government levels. In June and July 2025, an actor used AI-generated voice technology to impersonate the U.S. secretary of state, making calls and leaving voicemails that deceived senior officials. If experienced ministers and staff can be misled by convincing audio, so can a retiree at home. Surveys support this view. In late 2024, more than four in five older adults expressed concern about deepfakes, which are highly realistic fake videos or audio recordings, and voice cloning. This technique creates a synthetic voice that sounds like a real person, with many having encountered AI-enabled scams firsthand. Anxiety does not guarantee perfect defense, especially under the pressure of fear and urgency. This is a collective systems issue, not just a failure of individual training.

Build “limited access” by design, not by stigma

The drastic suggestion to cut older people off from their money is impractical and encourages discrimination. However, the core idea points to something helpful: automatically limit access to high-risk actions. The solution is not blanket bans; it is targeted friction. This means implementing daily caps on new payees and first-time crypto or wire transfers, establishing cooling-off periods for high-risk disbursements, and requiring mandatory call-backs to a verified number before funds are released. It also involves routing flagged transactions to an independent review desk, which can place a hold when exploitation is suspected. Financial regulators already support parts of this approach. In the U.S., broker-dealers can pause disbursements when they suspect exploitation and are encouraged to collect a “trusted contact” when an account is opened. States modeled on NASAA’s act permit temporary holds and mandatory reporting to protect vulnerable adults. The legal framework for tiered safeguards is in place; it needs to extend from securities to everyday payments.

A successful model exists abroad. The United Kingdom launched a mandatory reimbursement program for authorized push-payment scams in October 2024. Payment firms must reimburse most victims up to £85,000, sharing costs between sending and receiving institutions. Within a year, reimbursement rates increased, and claim resolution times improved. This shows that change is possible. You may disagree with the cap, but you can still recognize the design logic: when institutions must pay, they implement friction earlier, invest in analytics, and slow suspicious transfers. A U.S. version would not eliminate AI elder fraud, but it would change incentives and allow time for crucial decisions. Those moments are where doubt can develop, and a trusted contact can follow up. They are the moments when a teacher, banker, or adult child can intervene before the wire transfer goes through. This success story should motivate us to push for similar changes in the U.S.

What schools, banks, and regulators must do next?

Education systems cannot overlook AI elder fraud because families and school communities serve as the first line of defense. Schools already hold parent nights on device safety. They can add brief, straightforward sessions on family verification plans: agree on a “safe phrase,” establish that no one sends money based on a call or text, and confirm that emergencies go through a known number. Teenagers can practice calling a grandparent back from a saved contact and asking a verifying question. Teachers can incorporate five-minute, story-driven lessons into civics and digital literacy courses. None of this portrays older adults as naïve. It frames the family as a team combating automated manipulation. The same strategies apply to caregivers and community colleges. The goal is to normalize pauses under pressure and practice that in calmer moments.

Banks and payment firms need to incorporate a pause. New payees should trigger a brief “are you sure?” hold and a clear warning that names, caller ID, and even voices can easily be faked. High-risk transactions—such as first-time crypto purchases, emergency wire transfers, or transfers resulting from unsolicited contacts—should default to a 24-hour cooling-off period, with a simple way to reach a human. Firms should gather trusted contacts as a standard practice and utilize them when patterns appear suspicious, consistent with existing FINRA rules and state models for suspected exploitation. Telecom regulators must complete the job on call authentication to reduce the number of spoofed calls. The STIR/SHAKEN framework exists in the United States, with the current focus on expanding coverage and enforcing stronger measures on legacy and VoIP networks. None of this prohibits innovation. It simply requires that the fastest channels in finance and telecom contribute their share to risk management.

The statistic that started this essay is harsh because it is real. More than $12 billion in one year; nearly $4.9 billion lost by older adults alone. Those figures are not abstract totals. They represent mortgages, medications, and years of hard work. AI elder fraud is not a fleeting scare. It is a persistent reality in a world where anyone’s voice can be replicated and any transfer can be completed in minutes. We cannot teach our way out of this structural risk. However, we can redesign the points where harm occurs. We must give institutions a reason to introduce friction. We need to provide families with rehearsed steps to verify. Regulators must be instructed to delay the riskiest transactions by default. Finally, we should offer older adults both respect and a safer system. If we do this, the same statistic will tell a different story next year—fewer wires, fewer tears, and a new social norm: slow down before you send.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AARP. (2024, April 3). AI fuels new, frighteningly effective scams. Retrieved from AARP.

AARP. (2024, December 31). Older adults are concerned about AI scams and fraud. Retrieved from AARP.

Federal Communications Commission. (2025, April 29). Call authentication and robocall mitigation (STIR/SHAKEN). Retrieved from FCC.

Federal Trade Commission. (2024). Consumer Sentinel Network Data Book 2024. Washington, DC.

Federal Trade Commission. (2025, August 7). False alarm, real scam: How scammers are stealing older adults’ life savings. Data Spotlight.

FINRA. (2025). Trusted Contact Persons and temporary holds to address financial exploitation (Rules 4512, 2165). Retrieved from FINRA.

Fung, N. L. K., et al. (2023). Facial trustworthiness and age differences in buying intention. Innovation in Aging, 7(5).

IC3/FBI. (2024). IC3 Annual Report 2024. Washington, DC.

IC3/FBI. (2025, June 13). Elder fraud losses and complaints rise in 2024. FBI Boston Field Office release.

NASAA. (2023). Model Act to Protect Vulnerable Adults from Financial Exploitation (legislative commentary). North American Securities Administrators Association.

Payment Systems Regulator (UK). (2024, Oct. 2). PS24/7—Faster Payments APP scams reimbursement requirement. London.

Payment Systems Regulator (UK). (2025, Oct.). One year on: Impact of APP reimbursement on victims. London.

Pehlivanoglu, D., et al. (2024). Phishing vulnerability compounded by older age. PNAS Nexus, 3(8).

Reuters. (2025, July 8). Rubio impersonator used AI in calls to foreign ministers.

The Guardian. (2025, July 8). AI scammer posing as Marco Rubio targets officials.

University of Florida. (2024, Aug. 12). Older age shown as major risk factor in falling for phishing scams.

Wiley/Alzheimer’s Association. (2025). Boyle, P. A., et al. Scam susceptibility and accelerated onset of Alzheimer’s disease dementia.