East Asia’s Baby Bust: De-Risking Marriage Is the Missing Lever

Input

Modified

Childcare subsidies alone haven’t raised births in Korea, Japan, or China The binding constraint is marriage risk—up-front costs and divorce/career exposure De-risk marriage with clear legal defaults, lower entry costs, and work guarantees

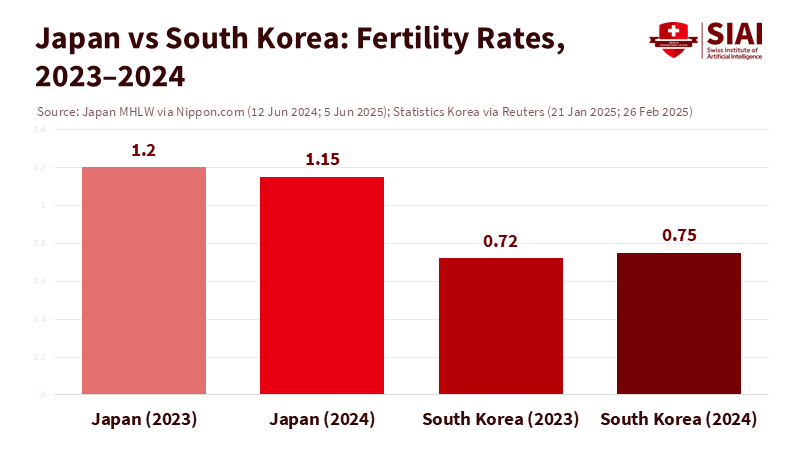

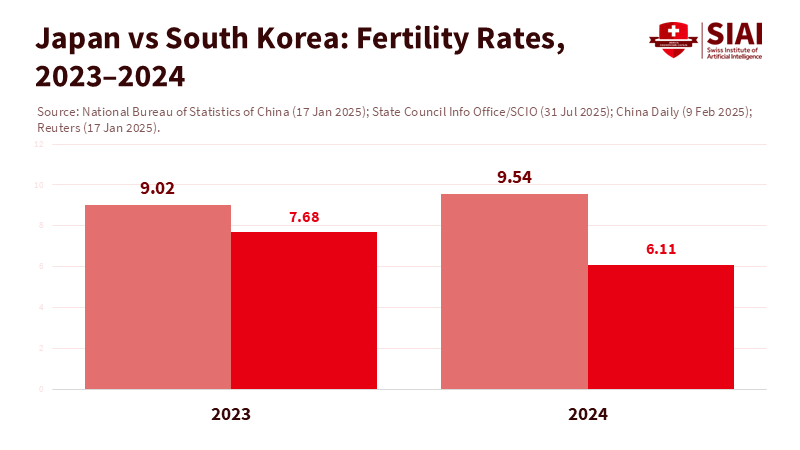

South Korea invested hundreds of trillions of won in family policies after 2006, but by 2023, its total fertility rate dropped to 0.72, the lowest in the OECD's history. In the following year, it slightly increased to 0.75. The message is clear. If significant spending on childcare, parental leave, and allowances were enough to boost birth rates, we would have seen a consistent rise by now. This has not happened. Japan, which also expanded support, recorded only 720,998 births in 2024, the fewest since 1899, despite years of adjustments to subsidies and childcare. While China's 2024 birth rate increased modestly from 2023, the number of new marriages fell to a record low of 6.1 million. The common issue is not the cost of diapers or daycare. It’s the risk involved in starting a household: the financial and social costs of marriage, as well as the potential fallout if a relationship ends. Without a clear strategy for de-risking marriage, East Asia’s fertility policies will keep treating the symptom, not the cause.

The Missing Third Axis: De-Risking Marriage

Most discussions treat fertility as a two-dimensional budget. One side includes direct child costs—housing, food, education, and childcare. The other side consists of time costs—career impacts, commuting hours, and the mental strain of care. However, young adults in East Asia, especially those in cities, are now considering a third dimension. They factor in the risks of marriage, which include the upfront costs of tying the knot and establishing a home, the ongoing risks if the relationship ends, and the career penalties that can be difficult to navigate in conservative job markets. For instance, in Korea, the gender pay gap was about 29 percent in 2023, with extended hours and rigid schedules. This gap heightens the perceived penalties of marriage and motherhood for women, while men face financial burdens, expecting to cover more of the mortgage. In Japan, although the “M-curve” has leveled off, regular employment for women continues to decline after marriage and childbirth. When these risks seem overwhelming, a new daycare center doesn't alter the fundamental decision.

A focus on marriage risks provides insight into why birth rates decline even when childcare slots increase or stipends rise. Take Korea, for example. After nearly two decades of policy initiatives that included cash grants at birth, extended parental leave, and after-school programs, the 2023 fertility rate still fell to 0.72. Preliminary data for 2024 indicate a slight increase in births for the first time in nine years; however, the actual number remains well below replacement levels, and the long-term outlook is uncertain due to a dwindling number of marriages. Major transportation projects, such as Seoul’s GTX, are intended to save time and reduce housing costs, but they don't address the marriage-related risks. Many couples weigh the potential downsides of a failed marriage—such as asset sharing, legal fees, child support, and career impact—against the benefits of a small monthly stipend or a shorter daycare waitlist.

De-Risking Marriage in Korea and Japan: What Worked—and What Didn’t

Korea illustrates clearly that childcare alone is not the key factor. Since 2006, government and city programs have invested an estimated US$207 billion to US$267 billion in support for family growth, including monthly allowances, “first-meeting” grants, childcare subsidies, and tax breaks. Yet the fertility rate fell to 0.72 in 2023. Preliminary figures for 2024 indicate a slight rebound to 0.75, partly due to a post-pandemic surge in marriages, rather than a fundamental change in how safe marriage feels. The average age for first marriages is in the early thirties, and long working hours remain common. These factors heighten the perceived costs of forming a household. Policies that cut commuting times and expand childcare ease the first two dimensions, but don’t protect against divorce or the challenges that come from taking breaks for family reasons.

Japan presents a similar situation from a different perspective. Despite years of subsidies, expanded childcare, and local matchmaking programs, 2024 saw the fewest births on record, totaling about 721,000, while the total fertility rate fell to 1.20 in 2023. Labor market trends often push many women into irregular jobs after marriage or childbirth, limiting their income growth and making the prospect of divorce seem more daunting. If a split results in diminished job security and a greater chance of single-parent responsibilities at a lower wage, then generous nursery coverage appears to be a partial solution. Policymakers often overlook the fact that when career risks and legal uncertainty are significant, the benefits of investing in childcare are minimal. It assists families who have already chosen to have children, but does not create families.

China's Marriage-Market Math

China's birth rate increased slightly in 2024, but the number of marriage registrations dropped to a record low of 6.1 million. Such a thin pipeline cannot support a lasting rise in births. More revealing is why the marriage registrations fell. The financial burden of marriage has risen sharply. Expectations for bride prices (caili) have increased in many areas, and marriage-related housing costs remain substantial. 'Caili' refers to the traditional practice of the groom's family giving money or gifts to the bride's family as part of the marriage arrangement. Reports indicate average claims for caili can reach several months or even years of local income, with higher amounts demanded in rural regions. The government has tried to manage these costs, but pressures continue. Add to this the fear of an expensive divorce. Although a mandatory “cooling-off” period initially reduced divorce rates, later data show they are once again on the rise. This legislative debate itself signals to young people that marriage is risky enough to require procedural barriers. In this environment, childcare subsidies cannot fix the deeper concerns surrounding marriage.

A straightforward method note clarifies the extent of the issue. Think of a young couple's anticipated marriage costs as three parts: initial expenses (wedding, housing deposits, caili), career penalties (lost income during breaks), and a risk factor for dissolution (legal fees and support obligations multiplied by the perceived chance of divorce). Even using conservative estimates from outside East Asia, a contested divorce can easily lead to five-figure legal fees. The financial impact of a career interruption compounds over time. If a couple estimates the risk of a career interruption at a one-in-five likelihood over their lifetime, the expected financial burden becomes significant. In China, where initial outlays can include a hefty caili and a home purchase, the total expected cost can overshadow any childcare subsidy. It’s not about diapers; it’s about the risks involved.

A Policy Blueprint to De-Risk Marriage

The appropriate response isn’t to eliminate childcare. It’s essential to view childcare as necessary but insufficient, and also to address the third axis with equal effort. First, decrease upfront marriage costs. Local governments should limit or strongly discourage transfer demands, such as caili, and lessen the connection between marriage and home purchases. When caps are difficult to enforce, governments can offer standardized low-interest “family formation” loans with strict limits and clear repayment rules to avoid a hidden market for “bride-price loans.” Public housing allocations for newlyweds should be transferable across districts to match job locations, and eligibility should be determined by combined income rather than household registration quirks. These steps reduce barriers to marriage without requiring payment for births.

Second, protect against the downsides. Family law can reduce uncertainty by establishing more explicit rules for asset division and child support, speeding up mediation, and providing straightforward calculators. The goal isn’t to simplify divorce; it’s to make the risks understandable and manageable. Standardized prenuptial templates approved by the courts could serve as defaults unless couples choose to opt out. Employers should be required to offer “career continuity guarantees” that maintain job levels and salary trajectories after parental leave for a set period, monitored by labor authorities. Universities and teacher-training programs can play a crucial role by establishing clinics that educate students in their final year on family finance, legal literacy, and conflict resolution. This is educational policy, not social engineering. It equips couples with the skills to handle risks effectively.

Third, lessen the career penalties associated with marriage, not just childcare penalties. Korea’s gender wage gap will persist without shorter work hours, predictable schedules, and regulations on pay transparency that are enforced. Japan continues to push many married women into irregular employment; changing those roles to regular positions with real opportunities for advancement would reduce the perceived drawbacks of starting a family. Educational administrators should contribute by expanding guaranteed, affordable after-school programs that stay open until early evening, aligning school calendars with job schedules, and developing staffing strategies that don’t default to mothers for emergency care gaps. These changes will decrease the time-related risks that contribute to the third axis.

Fourth, avoid interpreting short-term increases as significant changes. The uptick in Korea in 2024 is welcome, but a one-time surge in marriages and base effects drove it. Comparing that increase to the scale of spending reveals that childcare alone is not enough to shift the balance. In Japan, despite the introduction of additional childcare spaces and new allowances, births continued to decline in 2024. In China, a slight rise in births accompanied a significant drop in new marriages. Policymakers should focus on areas where elasticities are strongest—minimizing the upfront and downside risks of marriage—while treating childcare as the necessary support it is.

If we want more children, we first need to make forming a household safer. The past two decades have demonstrated that even substantial childcare budgets cannot mitigate the perceived financial and legal risks associated with marriage in East Asia’s major cities. Korea’s US$207 to 267 billion investment ended with a record-low fertility rate in 2023. Japan's birth rate hit a historic low in 2024, despite the introduction of new support measures. China saw its marriages drop to a record low in 2024, limiting the future birth pipeline. The math is harsh. A stipend cannot offset the risk of failure. The way forward is clear: lower upfront marriage costs, clarify the dangers with predictable laws and easy-to-understand calculators, and reshape work to ensure that family life doesn’t hinder careers. Schools and universities can contribute by teaching the necessary skills and providing schedules that enable families to thrive. If this is achieved, childcare investments can start yielding real demographic benefits. If not, we risk continuing to invest in the wrong areas.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Associated Press. (2025). Japan’s birth rate fell for a ninth consecutive year in 2024 to hit a record low.

Bloomberg. (2023). China cracks down on costly ‘bride price’ custom to boost births.

Economist. (2025). Bride prices are surging in China.

Financial Times. (2025). Japan births fall to lowest in 125 years.

Guardian. (2024). South Korea’s fertility rate sinks to record low despite $270bn in incentives.

Korea Herald. (2024). [Editorial] ₩100m childbirth incentive.

Hankyoreh. (2025). Average age at first marriage 33.9 for men, 31.6 for women in 2024.

MDPI / Social Sciences. Zheng, W. (2024). The impact of divorce cooling-off period on registered divorces in China.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2024). Population data: births and deaths, 2023.

Nippon.com. (2024). Japan’s total fertility rate hits new low of 1.20 in 2023.

Northwestern Mutual. (2025). How much does divorce cost?

OECD. (2024). Korea’s unborn future (EN).

Reuters. (2024). South Korea’s fertility rate dropped to a fresh record low in 2023.

Reuters. (2024). South Korea hopes new speed train links will help boost birthrate.

Reuters. (2025). South Korea birthrate rises for first time in nine years; marriages surge.

Reuters. (2025). China’s population falls for a third consecutive year; 2024 births and birth rate.

Seoul-based KEIA / The Peninsula. (2023). Korean policies to reverse the decline in the fertility rate (Part 1): Balancing work and family.

The Guardian. (2025). China’s new marriages hit record low; divorces on the rise.

Think Global Health. (2024). South Korea’s plan to avoid population collapse.

VOA Learning English. (2025). Researchers: South Korea’s birth rate increase last year unclear.

World Bank / Data. (2023). Fertility rate, total (births per woman) — Japan.

Xinhua / SCIO. (2025). China’s marriage registrations down in 2024.