Higher Education as a Commodity or a Right? Funding Excellence in the Demographic Crunch

Input

Modified

Higher education now behaves like a market good, and price signals matter Governments should fund fewer, stronger universities and tie money to outcomes Demographic decline demands ruthless quality control, clear labeling, and real bridges to opportunity

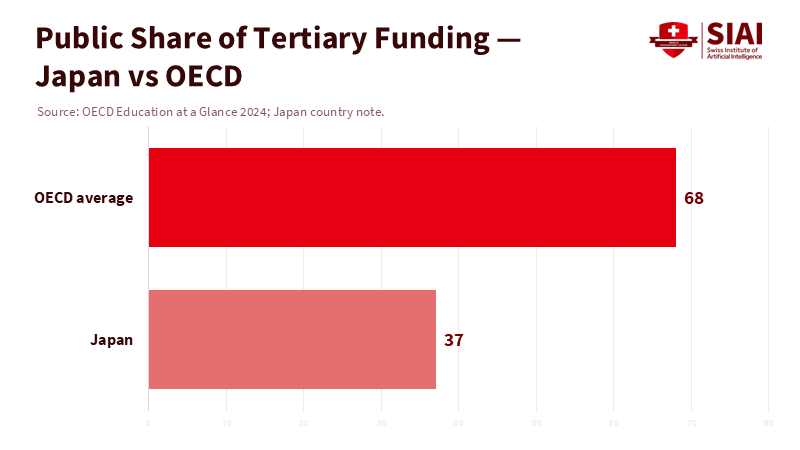

The number that shapes the debate is fifty. About half of all spending on Japan's universities comes directly from households, compared to around one-fifth across the OECD. When families bear such a significant burden, higher education as a commodity becomes a reality rather than just a concept. The price influences who enrolls, who graduates, and which institutions thrive. It also highlights a deeper trade-off that shrinking, aging societies can't ignore. If public budgets are limited and the number of 18-year-olds is decreasing, spreading the same funding across every campus risks securing less education at a higher cost per graduate. The real question is not whether universities offer a product; they do. The question is whether governments should continue to support the same mix of products, at the same level of quality, for the same number of institutions, especially when graduation rates are low and job markets are evolving. The uncomfortable but urgent answer is no. We should invest more—much more—in top-tier teaching and research, but support fewer institutions to achieve this.

The New Math of Higher Education as a Commodity

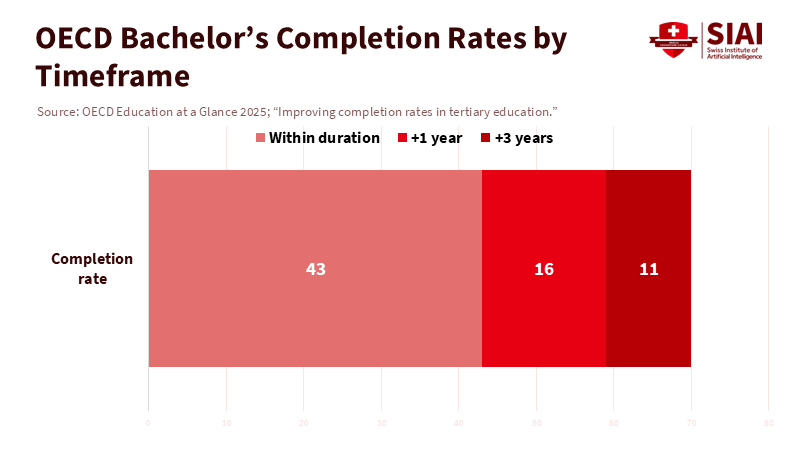

The previous promise was straightforward: more degrees would lead to more growth and more opportunity. This still holds on average, but averages can be misleading. OECD data indicate that the private return on a college degree is substantial; however, completion rates are inconsistent, and timelines are often extended. Only about 43 percent of bachelor's students in OECD countries graduate on time; even with generous extensions, the graduation rate reaches 70 percent. A system that treats degrees as paths to success but finances seats rather than successful outcomes risks wasting public funds and students' time. In a world where higher education is a commodity, tuition is set by the market. It reflects quality; the key metric for public finance is the cost per completed, labor-market-relevant degree, not the price per enrolled student. Funding rules and accountability should shift to this metric as the norm.

Pricing makes the model clear. Japan's national universities typically charge around ¥535,800 per year in tuition, with additional admission fees. Private universities often charge about double this amount, and some programs may charge even more. At the same time, OECD's 2024 country note finds that households cover almost half of tertiary costs in Japan, while the government's share is only 37 percent—unusually low for a developed country. When households bear that burden, pricing becomes significant, and families pay more attention to perceived program quality, job placement, and time to graduation. In this context, broad, indistinguishable subsidies fall short of the mark. Targeted, results-based funding becomes the efficient approach.

Demographics, Diploma Mills, and the Quality Problem

The demographic shift tightens the squeeze. South Korea's fertility rate dropped to 0.72 in 2023 and rose slightly to 0.75 in 2024, still well below the replacement level. Fewer births today mean fewer first-year students tomorrow, and Korean analysts already warn of campuses nearing crisis. The Korean Educational Development Institute reports a steady decline in university entrants linked to the shrinking school-age population. As seats remain unfilled, institutions either enhance their quality to attract scarce talent or lower their standards to stay afloat. When the latter choice prevails, "diploma mill" trends emerge, characterized by increasing fees, declining quality, and struggling graduates in the job market. CHEA emphasizes the need for strict quality assurance as the first line of defense against degree mills, which come in many forms. In a shrinking market, quality assurance must be uncompromising.

China presents a contrasting issue: mass production of degrees without adequate job opportunities. The class of 2025 is expected to reach a new high of approximately 12.22 million college graduates. Yet youth unemployment—calculated on a revised basis that excludes enrolled students—has remained in the mid-teens, reaching 16.5 percent in March 2025. Even with 13.35 million taking the gaokao (China's national college entrance examination) in 2025, the labor market cannot assure graduate-level jobs for all. This mismatch drives down wage premiums and creates a perception that some degrees have little value. The issue is not 'too much education'; it is too much education of the wrong kind and quality for the available jobs. Systems that regard higher education as a commodity must, therefore, monitor quality closely and adjust supply to meet demand—or risk losing public trust.

Pay Fewer, Pay More: A Competitive Model for Public Funding

The policy direction is clear. Governments should focus funding, raise compensation, and demand results. This means three key actions. First, concentrate public investment in a smaller number of stronger universities that demonstrate high teaching value, strong graduation rates within the expected timeframe, and consistent earning premiums. The aim isn't elitism; it's efficiency. Compensating departments that succeed and merging or shutting down those that do not will raise overall quality across the system. Second, pay faculty competitively in the institutions that meet these criteria. Attracting talent requires strong incentives. In areas where national goals depend on innovation—like AI, energy, and biomedicine—competitive pay is not just a benefit; it's a critical policy tool. Third, link a portion of public funding to the cost per graduate, rather than the cost per student, while ensuring equity. When higher education is valued as a commodity based on its quality through outcomes, tax funds should also reflect this value.

Critics may argue that this limits opportunity. That's true only if the rest of the system remains static. The solution is to create more short-cycle, lower-cost pathways that deliver strong job returns and to design flexible routes back to degree programs for those who demonstrate their ability to succeed. OECD data show that labor-market value, which refers to the worth of a degree in the job market, depends on national demand for skills and the system's structure; in some countries, the employment premium over upper-secondary education is modest, while in others, it's significant. Public funding should align with the premium, tailored to each program. Where the return is low, consider reducing or redesigning programs. Where the return is substantial, expand and subsidize access for low-income but high-potential students. Efficiency here isn't about cutting back; it's a choice to invest in more education for every public euro.

A Right Worth Earning: Guardrails for Access and Equity

If the state funds fewer universities more generously, it must ensure fair opportunities for admission. This begins in secondary school. Admissions should evaluate readiness using transparent, skill-based measures, not obscure and manipulable ones. Bridge programs must be genuine pathways, not waiting spots, with clear standards that lead to academic credit. Since only 43 percent of students finish a bachelor's degree on time in the OECD, providing support for completion is essential for equity, not just an option. Advising, course sequencing, mid-term remediation, and emergency financial aid can enhance graduation rates. Public dashboards should display program-level metrics, including entry standards, on-time graduation rates, time to degree, and median earnings three years post-graduation. The goal is not to penalize struggling students; it's to hold institutions accountable for the value they provide.

Price transparency must match quality transparency. Japan serves as a warning: households cover a significant portion of tertiary expenses, while tuition at public universities remains high, and private fees can be steep. Publishing the total expected cost to complete a program—not just the yearly tuition—helps families make informed comparisons. National resources already provide fee ranges; universities should also list the typical duration to graduation for each program. This alone can eliminate hidden costs. When families pay for education directly and the state contributes, both should have access to clear information. In a model that views higher education as a commodity, accurate labeling is integral to fairness.

What This Means for Japan, Korea, China—and Everyone Else

Japan's policy challenge is twofold: reduce system fragmentation while maintaining research quality. MEXT's School Basic Survey indicates that total university enrollment is near record levels. Still, undergraduate numbers are falling, and junior colleges are continuing to decline. Consolidation is not a threat; it is a means of preserving academic strength. Selectivity can remain high even as the youth population decreases, provided that weaker programs are merged or closed and stronger programs are expanded. Scholarships should then target students who meet strict standards but lack funding. This approach enables higher education to coexist as both a public good and a commodity, without slipping into a two-tier system.

Korea must act quickly to manage the impending drop in enrollment. Pressure will increase even if fertility rates stabilize at 0.75 because smaller cohorts are unavoidable. The likely response is a combination of campus mergers, repurposing unused land, and shifting focus to adult learners and international students. Some of this is already in progress. However, none of this addresses the core issue without a focus on quality. A policy that spreads funding too thin will prolong the existence of ineffective programs. A policy that supports fewer, stronger institutions—and establishes robust vocational pathways—can increase wages and maintain public confidence. The tricky part is accepting that not every degree holds the same value. The honest part is recognizing that taxpayers should not finance worthless degrees.

China's mass education system needs stronger connections to the job market. With over twelve million graduates and youth unemployment still elevated by global standards, the main goal is to direct resources towards programs that ensure job placement and to slow growth where returns are low. The gaokao still serves as a broad measure of aptitude, but it cannot guarantee demand. Public funding should reward departments that create stable jobs and strong earnings, while also scrutinizing those that do not. As in Japan and Korea, the solution is not less education; rather, it is better-aligned education and fewer institutions that fall short.

The key fact remains that households cover about half of Japan's higher education costs. This figure highlights the new reality for aging, high-income societies. Price is significant because families pay. Quality is crucial because job markets penalize subpar programs. And outcomes are important because public budgets are limited. Treat higher education as a commodity in terms of transparency, incentives, and accountability; treat it as a right, offering fair opportunities and absolute paths for those who need a second chance. This combination requires courage. It calls for funding fewer institutions with greater resources while demanding more in return. It necessitates shifting funding to focus on the cost per graduate and earnings, rather than enrollment. Most importantly, it requires acknowledging that mass expansion without quality is a promise we can no longer keep. Acting on this truth now can help preserve excellence, expand real opportunities, and ensure that the learning taxpayers—and students—believed they were financing is truly delivered.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Asia Society Policy Institute. (2025, September 3). The 19 Percent Revisited: How Youth Unemployment Has Changed Chinese Society.

CHEA (Council for Higher Education Accreditation). (n.d.). Degree Mills: An Old Problem & A New Threat.

KEDI (Korean Educational Development Institute). (2025, August 6). Decline in School-age Population, Rise in Adult Learners.

KOSTAT (Statistics Korea). (2025, February 26). Preliminary Results of Birth and Death Statistics in 2024.

OECD. (2024). Education at a Glance 2024.

OECD. (2025, September 9). Education at a Glance 2025: Who is expected to complete tertiary education?

OECD. (2024). Japan – Education at a Glance 2024 Country Note.

OECD. (2025, September 9). How does educational attainment affect participation in the labour market?

Reuters. (2025, April 17). China's youth jobless rate dips in March to 16.5%.

Reuters. (2024, November 14). Record number of students to graduate college in China in 2025.

Straits Times. (2025, June 7). Millions sit China's high-stakes university entrance exam; 13.35 million registered.

Study in Japan (JASSO/MEXT). (n.d.). Academic Fees (Universities and Graduate Schools).

Study in Japan. (2025, May 1). Result of International Student Survey in Japan, 2024.

University of Tokyo. (n.d.). Admission Fee and Tuition.