Longevity Economics in Latin America: The Real Cost of Longer Lives

Input

Modified

South America faces a $7.3T loss—about a 4% GDP drag—from unhealthy ageing Adopt longevity economics: prevention, midlife reskilling, and age-friendly work from 50–75 Tie funding to health and re-employment outcomes to turn ageing into a growth dividend

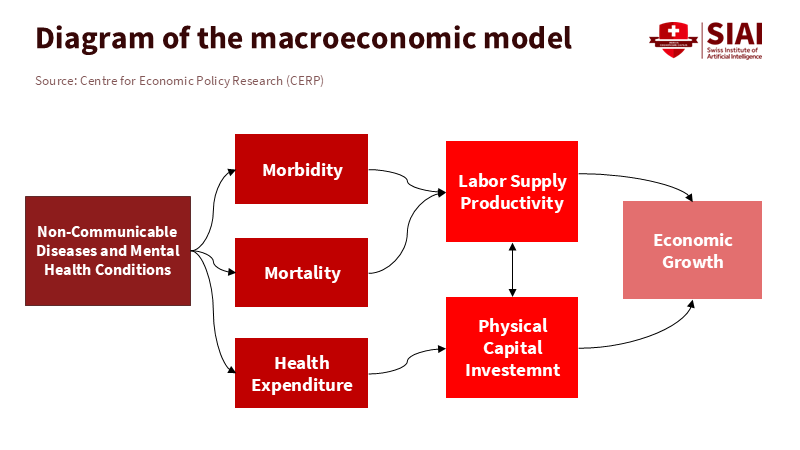

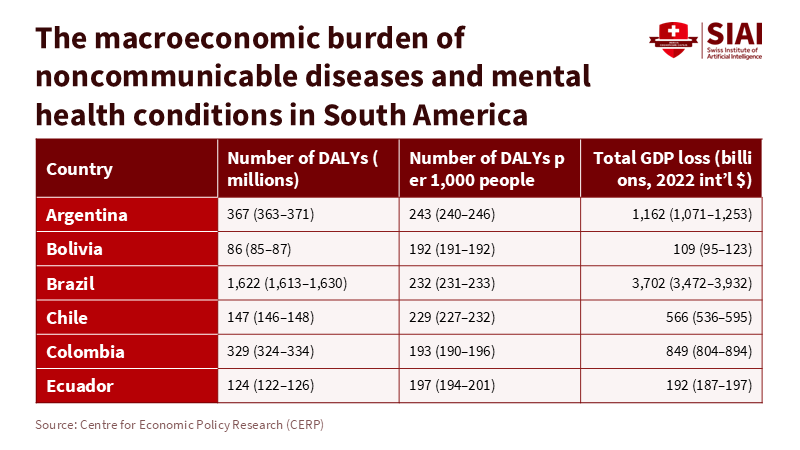

The key figure in this discussion is $7.3 trillion. This is the estimated loss in GDP that South American countries will face from 2020 to 2050 due to age-related diseases and mental health issues. This amounts to an average annual loss of approximately 4% of GDP. It's a harsh reality: longer lives without health and income are expensive. This sets the stage for longevity economics, the concept that longer lives need to be accompanied by healthier years and opportunities to earn, learn, and contribute. Without this balance, longer lives can strain budgets, slow growth, and increase inequality. Latin America must decide how to handle this. It can either treat longevity as an ongoing medical bill or redesign work, education, and welfare to ensure longer lives create value. The first option is too costly. The second, however, presents us with the best opportunity to transform a potential problem into a benefit, offering a hopeful future where longer lives can contribute to economic growth and prosperity.

Longevity economics: from burden to budget constraint

The $7.3 trillion figure is not just a far-off prediction; it represents a current budget constraint. Health issues in South America already reduce labor supply and shift spending from investment to treatment, leading to compounded problems over time. Simply put, fewer healthy workers mean slower economic growth. Data from the region backs this up. Health spending in Latin America and the Caribbean currently accounts for approximately 7.9% of GDP. This level offers little flexibility in handling rising costs associated with chronic diseases without compromising other vital areas. With noncommunicable diseases causing most deaths in the region, the current situation is likely to continue. Longevity economics encourages a shift in thinking: we should invest in prevention and the capacity to work rather than waiting to treat illnesses.

The fiscal situation is tight. In 2022, average tax revenues in Latin America and the Caribbean accounted for approximately 21.5% of GDP, which is significantly lower than the OECD average. In this context, a health-related expense that acts like a 4% annual tax on GDP is unsustainable. It would either increase deficits or result in cuts to other areas, often education and skills, which would undermine the productivity needed to support longer lives. The main point is that budgets alone cannot support longevity. We need to create an economy where older adults can contribute to the budget by staying healthier and continuing to work longer. That is how longevity economics should work.

Longevity economics and the missing middle years (50–75)

We often focus on retirement, but the crucial years are the two decades before and after it, what we call the 'missing middle years' (50-75). In the region, statutory retirement ages are typically in the early to mid-60s, and many older adults leave the workforce long before then—often due to health issues, caregiving responsibilities, or a lack of age-friendly jobs. Pension coverage is uneven; on average, about 69% of people over 65 receive a pension, but this varies widely by country. This makes the traditional 'work-then-stop' model both vulnerable and unjust. Longevity economics calls for a new phase of work and learning, from around age 50 to 75, where upskilling, flexible hours, and gradual retirement become the norm. This phase is critical because maintaining people's health and employment during this time provides significant economic benefits, given their valuable experience and the high cost of hiring replacements.

Global research supports this perspective. Studies on the longevity dividend suggest that benefits arise when longer lives are accompanied by good health, and institutions adapt to enable older adults to continue contributing to society. The message isn't to "work forever," but to "work differently, with support." This means adapting workplaces for older individuals, redesigning benefits to reward ongoing participation, and reshaping education to make re-entry simpler and more respectable. This also requires a significant cultural shift. We need to change the view of older adults from "cost centers" to valuable assets for growth when their health, skills, and employer practices align. This cultural shift is not just a nice-to-have, but a crucial element in the success of longevity economics.

Longevity economics under climate and health strain

Health is a critical factor. In the Americas, older adults can expect to live many additional years. Still, too many of these years are not spent in full health. Healthy life expectancy at age 60 in the region decreased during the pandemic and remains below the OECD average, highlighting a gap between life expectancy and health quality. Climate pressures worsen this situation: by 2050, an additional 200 to 250 million older people worldwide are expected to face dangerous heat conditions, with significant increases projected in South America. High temperatures can exacerbate cardiovascular and respiratory risks, resulting in increased hospital admissions. When older adults already face chronic health issues, extreme heat can hasten their retreat from the workforce and speed up the decline in their abilities. This results in higher health expenditures and fewer healthy workers, which goes against the principles of longevity economics.

This is why the hype around "living forever" is not just a distraction—it can be damaging. Critics argue that striving for extreme longevity can distract from the urgent and attainable goal of increasing healthy years for many rather than a select few. We need practical steps that shift expenses from late-stage treatment to early prevention, including managing hypertension, controlling diabetes, providing vaccines, preventing falls, offering mental health services, and ensuring access to cooling during heatwaves. These are not far-fetched goals. They form the foundation of public health and help safeguard both people and budgets. Longevity economics begins in primary care and public health, as well as in the neighborhoods where older adults live and work.

Longevity economics in action: campus-to-career systems for an ageing region

Education is the key to achieving healthier and more productive longevity. However, adult learning participation in Latin America is low, and mid-career options are scarce. We need universities, technical schools, and employers to establish a second-stage system that includes stackable credentials, recognition of prior learning, and quick transitions back into work. The focus should be on learners aged 45 to 70 who want to update their skills while managing health and caregiving responsibilities. Programs should be short, modular, and available during off-hours or online. Universities can become "longevity hubs," pairing gerontology clinics with career services for midlife workers and placing health coaches alongside academic advisors. This is not charity; it's a response to labor shortages in health, education, and green services—sectors that have recently grown and will continue to do so as populations age.

Policy needs to support this vision. Public funding should be linked to outcomes that matter for longevity economics, including helping people over 50 find employment at living wages, achieving measurable health improvements that reduce hospital visits, encouraging employers to adopt age-friendly job practices, and creating flexible benefits that allow for a gradual reduction in hours without losing insurance. Pension and tax policies should not discourage continued work. Health systems should provide equal reimbursement for proven prevention and treatment. Employment ministries should make midlife apprenticeships standard rather than unusual. Education authorities should recognize micro-credentials in fields where older workers excel—such as care coordination, mentoring, and complex services—so that experience counts. The essential question is: can a 58-year-old who needs new skills enroll in a program next week, learn without debt, and secure a job that fits their health and lifestyle? If the answer is no, the policy is missing out on potential growth.

We started with a stark figure: $7.3 trillion in lost output, equating to a 4% annual tax on GDP through mid-century if health burdens remain unchecked. This figure is alarming, but it also serves as a guide. It illustrates where the money goes when we allow longevity to progress without considering the impact on health and work. The solution is not to wish for shorter lives, but to establish longevity economics—prioritizing health, redesigning work, and offering on-demand learning. This approach ensures that longer lives can be self-sustaining and even beneficial. The region's budgets cannot afford to manage longevity merely as a cost; instead, they can invest in it as an asset, prioritizing primary care over intensive care, prevention over treatment, and active work and learning over retirement. Suppose universities, employers, and government agencies collaborate. In that case, the cost of longer lives can be transformed into the benefits of improved quality of life. The next decade will determine the outcomes we achieve.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AARP. (2024). Global Longevity Economy® Outlook. Retrieved October 8, 2025.

Bloom, D., Ferranna, M., et al. (2025, Oct. 8). The enormous economic burden of age-related diseases in South America. VoxEU/CEPR.

Brookings Institution. (2024, Jan. 29). The age of the longevity economy. Summarizes AARP findings on 50-plus GDP contribution.

Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). (2023). Employment and living conditions of the population over 50 in Latin America. Publications.iadb.org.

Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). (2025, Mar. 19). The demographic wave drives the silver economy in Latin America and the Caribbean. IDB Blog.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2025, June). Andrew J. Scott, The longevity dividend. Finance & Development.

Nature Communications. (2024). Falchetta, G., et al., Global projections of heat exposure of older adults.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) et al. (2024). Revenue Statistics in Latin America and the Caribbean 2024/2025.

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). (2024, Aug. 21). Impact of COVID-19 on healthy life expectancy of older adults in the Americas.

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). (2025, July 15). Major storm on the horizon: NCDs and mental health conditions to cost South America trillions. Press release.

TIME Magazine. (2024). Arianna Huffington, The Cost of Trying to Live Forever.

World Bank. (2025). World Development Indicators: Health—Current health expenditure (% of GDP), Latin America & Caribbean.