The Debt China Won't Name—and Why It Lands in the Classroom

Input

Modified

Local debt collapse and deflation push silent austerity into schools Beijing can prevent a bank crisis, not classroom payroll pain Protect operating budgets, ease family costs, and retool TVET

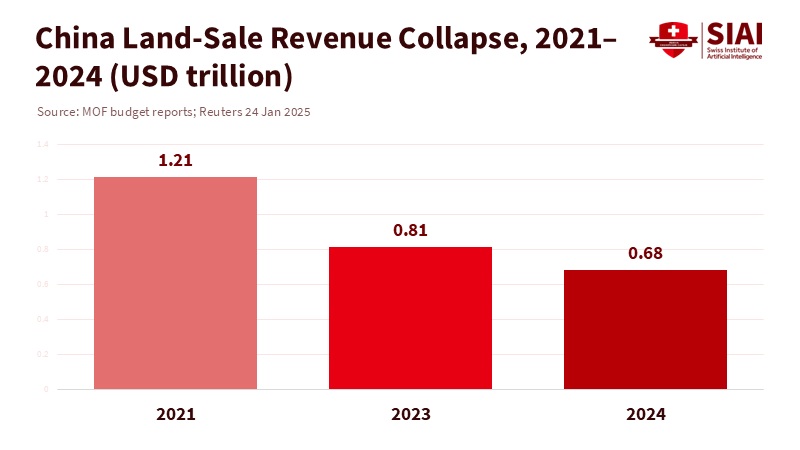

The number that will define China's next five years isn't the GDP or the unemployment rate; it's the drop in land-sale revenue that used to support local budgets. In 2021, local governments earned about 8.7 trillion yuan from land sales. By 2023, that amount fell to around 5.8 trillion yuan, and it dropped another 16 percent in 2024, according to the finance ministry. This isn't just a minor issue; it's crucial for subnational spending on essential items such as schools, buses, repairs, and teacher bonuses. The usual method for dealing with heavy public debt is to wait for inflation to reduce it. This doesn't work when prices are flat or declining. Deflation increases the real burden of nominal indebtedness and reduces nominal revenues at the same time. What looked like manageable debt with state control turns into slow, painful cutbacks. While there may not be an outright financial crisis, Beijing can manage rollovers and swaps. However, there is a real risk of social unrest if payrolls decrease, maintenance gets delayed, and cuts to education go unnoticed. The long-term implications of this issue are significant and require strategic planning.

Control Can Avoid a Bank Run; It Can't Fund a School Year

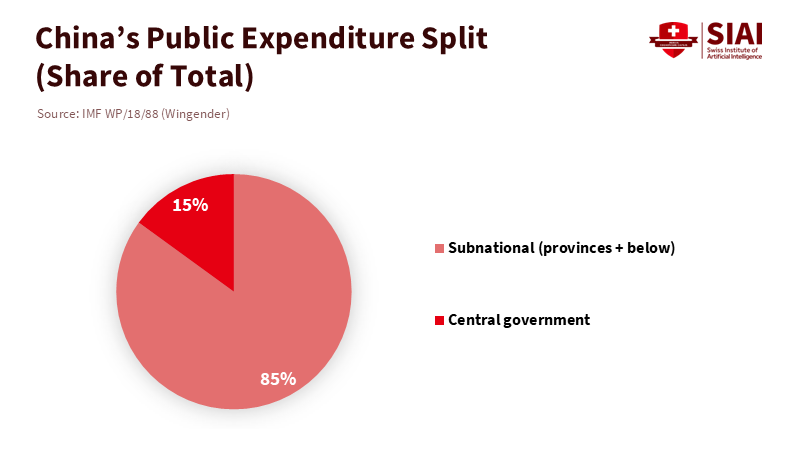

The heart of China's local debt issue is structural, not cyclical. The country delegates most public spending to provinces and lower levels of government while centralizing revenue collection. The IMF has called China "one of the most decentralized in the world" in terms of spending, with local governments responsible for about 85 percent of general-government expenditures. During the economic boom, land auctions helped bridge this gap and funded urban development, school construction, and various government-managed programs. When the property market stalled, local budgets faced significant strain. Even if political control keeps banks stable and prevents chaotic defaults, the money needed for teachers, heating bills, and school buses is often delayed or insufficient. This quiet austerity has a profound impact on daily life and gradually builds up over time.

Beijing has sought to buy time. In November 2024, lawmakers approved a multi-year plan to convert hidden local government financing liabilities into formal provincial bonds, allowing for up to 6 trillion yuan in new swap capacity. This is aimed at lowering interest costs and extending maturity to prevent a crisis. At the same time, the central government increased local special bond quotas and began rolling out ultra-long special treasury bonds for national priorities from late 2024 through 2025. These measures are essential. They alleviate immediate funding pressures, mitigate rollover risks, and demonstrate the state's support for subnational finances. However, they don't replenish land-sale revenue and do not change the fact that nominal growth remains weak. Without new, reliable revenue for local governments, the inclination is to save money by delaying non-essential spending first, which often means postponing teacher recruitment, repairs, and small but impactful programs that usually lack attention. This situation highlights the importance of international investors adopting cautious and diversified approaches.

Deflation changes the strategy. In 2024–2025, producer prices were negative or close to zero, and the CPI hovered near zero often enough to matter. In this environment, debt-to-revenue ratios worsen even if real growth is decent because nominal cash flow stalls. Beijing's response has been to speed up government issuance and front-load subsidies for equipment upgrades and trade-ins, while encouraging localities to keep using special bonds for investment. The danger for education comes from being overshadowed by capital-intensive projects that are easier to label as stimulus, even though the most significant immediate returns would come from preserving operational budgets for schools and universities. While control can extend a loan, it cannot generate a year's worth of reliable funding without a solid revenue base to rely on.

Deflation Doesn't Just Raise the Bill—It Rearranges Strategy

The secondary effects of deflation are political and strategic. When prices are flat, households save more and put off purchases; costs for fee-based services, including education, become heavier. Local administrators often resort to "temporary" hiring freezes. University deans see lab upgrades stalled due to funding that doesn't materialize. Beijing's swap-and-bond approach stabilizes things but directs limited financial resources toward repairing balance sheets and making targeted investments, rather than providing overall operational support. The trade-off is clear: the center can maintain economic stability while continuing to underfund the human systems that drive productivity gains. This is why the common assertion that "there will be no crisis because the state controls finance" is true but misses the broader issue. The risk isn't a visible bank run; it's a gradual decline in service quality that undermines trust in classrooms and clinics before it ever impacts bond markets.

What's crucial now is how these choices influence China's standing in the world. To support the swap program, ultra-long issuance, and larger local quotas without alarming domestic markets, Beijing must maintain tight control over factors that could create instability: capital flows, messaging, and the pace of opening up. This control approach fits awkwardly with any desire for deeper international financial integration. If nominal debt rises faster than nominal income, the instinct for the central government is to conserve resources and postpone expansions. In short, a focus on repairing balance sheets likely means a narrower, more domestic outlook; international economic expansion—especially the kind that relies on foreign capital's confidence—loses priority. This limitation is not ideological; it is practical. The more the government needs to manage rollover risks and stabilize yields, the less room there is for external market signals to influence prices or economic speed.

For education policy, this domestic focus has significant implications. First, prioritize basic needs with firm rules: teacher pay and school operating budgets in poorer areas should be partially protected by formula-based central transfers that automatically increase when local revenues fall, not by ad hoc requests after debts accumulate. Second, treat small but impactful support for households as part of macro policy, including transport vouchers, dorm fee reimbursements, and limits on non-instructional fees to maintain participation during times when families might cut back. Third, shift higher education and vocational training priorities toward areas where domestic growth and productivity gains align—like power equipment, industrial software, and medical devices—and connect grants to partnerships with industry, measured by practical impacts instead of simply patent numbers. None of these measures is flashy, but they can help maintain stability even when deflation leads to delays.

"No Financial Crisis" Is Not the Same as "No Crisis"

For those watching from outside China, the best approach is neither to panic nor to be complacent. The most likely scenario is years of balance-sheet adjustments without a major market collapse. This requires practical planning. Universities and schools that depend on Chinese enrollments or funding from joint labs should conduct two-year stress tests assuming flat or slightly falling revenues, and establish connections in Southeast and South Asia without viewing any one country as a direct substitute. Partnerships with Chinese institutions will continue, but they will be safer if grounded in open-science standards, reproducibility, and clear data governance rules. Education providers in emerging markets—the Gulf, parts of Africa, and ASEAN—can use this time to create modular programs in logistics, compliance, green supply chains, and cross-border payments that align with current policy trends: pragmatic, skills-oriented, and less reliant on unstable capital cycles.

Domestically, Chinese policymakers face a choice. Suppose the aim is to prevent a civil crisis while managing the financial situation internally. In that case, the most valuable expenditure in the next two years should be on supporting teachers, maintaining class sizes, and ensuring that bus routes and dorms remain operational. This means shifting some funding from capital projects to operational support in education and related services, even if it means slowing down high-profile projects. It also means recognizing the reality shown in the data: land-sale revenue is not going to return to 2021 levels anytime soon, and waiting for inflation to diminish debt is unrealistic in a deflationary or nearly flat-price environment. The sooner budgets reflect this reality, the fewer "temporary" cuts will become permanent.

Skeptics may argue that the refinancing measures from 2024 to 2026 and the increase in ultra-long sovereign bonds already tackle the core issue. They are helpful, but the numbers still present challenges. With land income down by a third from its peak and facing another drop in 2024, nominal revenues are lower and more inconsistent. Meanwhile, the bond program exchanges short-term, higher-cost liabilities for longer, cheaper ones. This is good policy, but the principal remains, and the real burden grows when prices stagnate. Suppose we accept that Beijing's control keeps a crisis at bay. In that case, the real test is whether the government can provide reliable operating cash flows for subnational budgets to maintain schools while managing risks elsewhere. This is how future budgets will be assessed.

The geopolitical aspect is another reason to expect a focus on domestic issues. Gaining the trust of foreign investors while managing yield curves, rationing credit, and cleaning up property issues is challenging even in the best circumstances. It becomes even harder when global conditions involve tariff shocks and tighter monetary policies. The state can prioritize flagship international projects and keep some financial channels open. Still, a wide-ranging international expansion necessitates more price discovery and legal reliability than a stressed system can easily handle. If the choice is between domestic financial repairs and an ambitious global strategy, the debt situation and deflationary pressures point strongly toward the former for the foreseeable future.

We started with land sales that fell from 8.7 trillion yuan to 5.8 trillion yuan, followed by another drop in 2024. This illustrates how a national debt issue transforms into an education issue. The government can, and likely will, prevent financial systems from collapsing. However, it cannot expect teachers, parents, and students to endure endless "temporary" cuts without consequences. The path forward is clear. Secure protected operating transfers for essential education; use targeted support for households to keep participation rates high; focus higher education and vocational training on sectors that boost domestic productivity; and, internationally, reduce risks while developing programs that align with real labor market needs. If these steps are taken, China can buy the time it seeks without sacrificing the educational services that provide credibility to its growth. Failure to do so will reveal that the first crisis people experience isn't reflected in bond prices but is felt in classrooms—and once trust in the school erodes, it takes much more than a simple financial adjustment to restore it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News. (2024, November 8). China approves $840B plan to refinance local government debt, boost slowing economy. Retrieved September 22, 2025.

IMF (Wingender, P.). (2018). Intergovernmental Fiscal Reform in China (WP/18/88). Retrieved September 22, 2025.

Peterson Institute for International Economics. (2024, July 5). Chinese local governments' reliance on land revenue drops as property downturn deepens. Retrieved September 22, 2025.

Reuters. (2024, November 8). China unveils steps to tackle "hidden" debt of local governments; 6 trillion yuan bond swaps approved. Retrieved September 22, 2025.

Reuters. (2024, December 24). China plans record special treasury bond issuance next year. Retrieved September 22, 2025.

Reuters. (2025, January 3). China will sharply increase funding from ultra-long treasury bonds in 2025. Retrieved September 22, 2025.

Reuters. (2025, January 24). China's 2024 local government land sales see 16% drop in revenue. Retrieved September 22, 2025.

Reuters. (2025, March 27). China accelerates government bond issuance in Q1 to highest on record. Retrieved September 22, 2025.

ThinkChina (Chen, K.). (2025, May 2). China's deflationary trap: Can Beijing fix its broken economic model? Retrieved September 22, 2025.

Comment