Not Guinea Pigs, Not Glass Domes: How to Design AI Toys That Help Babies Learn

Published

Modified

babies is inevitable—focus on smart guardrails, not bans Mandate strict privacy, proven developmental claims, and designs that boost caregiver–infant serve-and-return Advance equity with vetted, prompt-only co-play tools in public settings and firm vendor standards

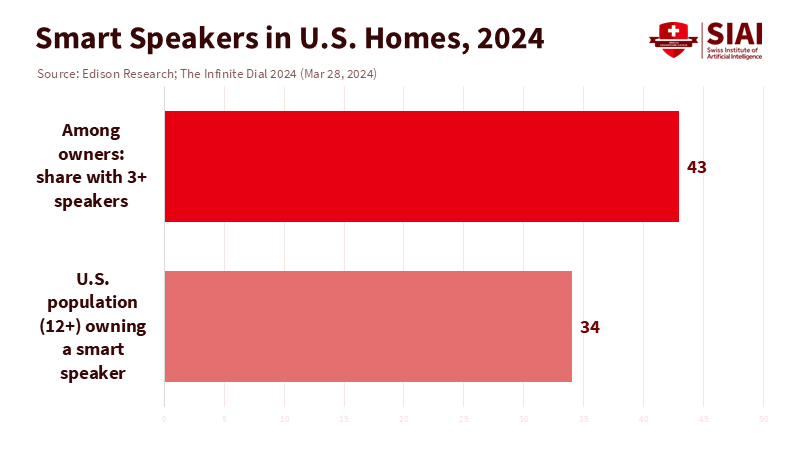

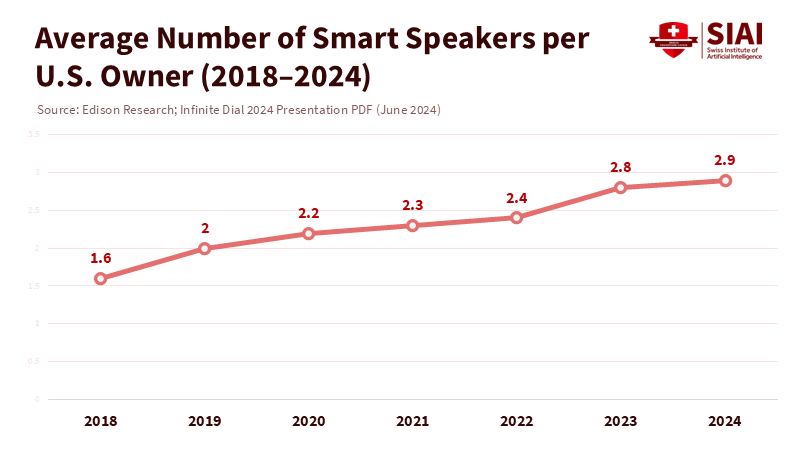

A child born today will likely spend their early years in a home where a voice assistant is always listening. In the United States, about one in three people aged 12 and older have a smart speaker. Many of these owners have more than one device placed around the house, where babies nap, babble, and play. At the same time, the global market for connected toys is racing toward tens of billions of dollars by the end of the decade. These facts reveal an uncomfortable reality: whether we like it or not, infants will grow up around artificial intelligence. However, the potential of AI toys is not to be feared. Our choice is not between exposure and purity. We must decide between passive gadgets that collect data and impair human interaction, and well-regulated tools that have the potential to enhance it. If we want the latter, we must establish rules now that prioritize what matters most in the first thousand days: responsive human conversation and touch.

The Right Question: Replace or Relate?

The main issue is not whether a device is "AI." The problem is whether it replaces or relates. Language and cognitive skills in the early years depend on "serve-and-return" exchanges—those quick conversations between a caregiver and a child. Multiple studies show that the number of exchanges, rather than the total number of words a child hears, is linked to stronger language development and later success. These findings are based on observational audio recordings and neuroimaging studies that link conversational exchanges to both white-matter connectivity and language outcomes, with consistent effects across various research designs. For policy, it is essential to note that a bot talking to a baby is not the same as a tool that encourages a parent to interact with that baby. We should evaluate AI toys based on whether they effectively promote conversations and shared attention between humans, not on their ability to "engage a child."

This distinction also explains why screens continue to pose a problem for infants. Pediatric guidance is clear: for children under 18 months, avoid screen media except for video chatting. For toddlers, focus on high-quality content that adults watch with children, and set clear limits. The physiological findings align with this behavioral guidance. Babies learn best from responsive and interactive cues—voices that respond to their sounds, faces that match their expressions, and hands that share visible objects. A static video, no matter how well-made, cannot provide the same feedback. Pediatric recommendations are based on a combination of observational studies, parent coaching trials, and developmental neuroscience, emphasizing context rather than a universal time limit. This is not an argument against all technology. The standard is simple: if a device cannot show that it increases responsive human interaction, it does not belong in an infant's daily routine.

Guardrails That Enable, Not Ban

We should reject the false choice between fear and permissiveness. The way forward is to establish specific rules that distinguish between helpful and harmful designs. This will provide a sense of reassurance and security to parents, caregivers, policymakers, educators, toy manufacturers, regulators, and researchers. Privacy and security must come first, as trust is essential. Independent researchers have demonstrated that many "smart toys" transmit behavioral data to companies, often with inadequate encryption. This is unacceptable for any product aimed at children, especially babies. Regulators are making some progress. In the United States, new rules on children's privacy now require stricter consent and limit the monetization of kids' data. In Europe, the AI framework and existing children's design code focus on data reduction and best-interest principles, while the Digital Services Act prohibits targeted advertising to minors. These changes do not resolve every question about connected toys. Still, they establish a legal baseline: no silent data logging, no unclear user profiles, and no manipulative designs to increase screen time for toddlers. Procurement leaders in early-childhood systems should adopt this baseline immediately.

The second rule concerns claims. If a product advertises "language boost," it should be able to substantiate that claim. This involves conducting independent trials using validated measures, including tracking conversational exchanges through full-day audio recordings, measuring parent-reported outcomes against standardized tools, and incorporating stress or sleep measures when relevant. We do not need decade-long studies to take action, but we do need studies large enough to eliminate placebo effects and publication bias. Devices that monitor health require even stricter standards. Recent regulatory approvals have begun to separate true medical devices from consumer gadgets. That is progress, but the guidance for pediatric care remains straightforward: families should not depend on home monitors to lower the risk of SIDS. The proper path for AI-based infant health tools is narrow and supervised—through clinicians—and the claims should be limited to what the device is cleared to do. This emphasis on evidence-based claims will empower parents, caregivers, policymakers, educators, toy manufacturers, regulators, and researchers to make informed decisions about AI toys for infants.

The third rule is the design for co-play. An AI toy suitable for infants should function more like a "language mirror" than a talking advertisement. It should respond to a child's vocalizations and encourage the parent to identify what the baby is touching or to sing a timely song. It should quickly turn off unless an adult is present. It should work on-device by default, upload nothing without explicit permission for each use, and clearly explain—in simple terms—what data is stored, the purpose, and the duration. These principles are based on pediatric practices that emphasize parent coaching and legal requirements focused on data minimization and the best interests of children. They can support innovation by shifting the goal from "engagement time" to "human interactions per hour."

The final rule addresses equity. Wealthier families are more likely to buy structured toys or access parenting classes and speech therapy. If AI products become high-end items—or if "free" versions exploit data while paid versions keep it safe—we risk widening gaps in early language development. Public spaces, such as libraries or community health centers, can change this dynamic by providing supervised "co-play corners" equipped with evaluated devices and caregiver training. The key outcome to monitor is not how cleverly a toy speaks, but whether it helps busy adults communicate more often and effectively with their children.

What We Should Build Next

With these rules in place, we can consider future possibilities. Imagine a soft toy without a screen, equipped with a few touch sensors, and an on-device speech model designed to prompt rather than perform. The toy listens as a baby babbles while holding a soft block. Instead of lecturing, it signals the closest adult: "I hear sounds—want to try 'ba-ba-block' together?" The toy then goes silent. If the adult responds, it records the exchange and periodically offers another prompt based on the infant's movements—a tap song, a peekaboo rhythm, or a shared label for what the child holds. Over time, the parent receives a summary on their phone—not dopamine-driven "streaks," but patterns in their interactions with tips based on research. This represents AI as a conversational enhancer, not a substitute caregiver.

Now imagine a toddler's reading nook in a child care center. A small speaker sits beside board books. When an adult opens a book, the system listens for key words and suggests questions: "Where did the puppy go?" "Can you find the red ball?" The assistant does not narrate the entire story; it only supports interactive reading. Trials with preschoolers show that AI partners can, in specific settings, help with question-asking and engagement in stories at levels close to those with human partners. The transition to infants is not straightforward—infants require gestures and turn-taking more than questions—but the research is emerging. A responsible project would initially conduct pilot studies in high-need communities, designed with input from educators and parents, monitoring conversational exchanges and caregiver stress over several months.

Health devices will pursue a different direction. Here, the value is not "smarter parenting" but clinical supervision and peace of mind in specific circumstances: for a preterm infant just discharged, a baby with respiratory problems, or a family caring for a child on supplemental oxygen. Regulators have started approving infant pulse-oximetry devices for specified uses. That is helpful for those narrow cases. However, for healthy babies, the safest and most effective investments remain unchanged: practicing safe sleep, supporting breastfeeding when possible, ensuring smoke-free environments, and coaching caregivers. Policies should keep these priorities clear. Consumer wearables should not suggest they can prevent tragic outcomes when they cannot.

Educators and administrators have a fundamental role beyond procurement. Early-childhood programs can incorporate "talk-first tech" into staff training. A brief training session can show how to use a prompt-only toy to encourage naming, turn-taking, and gesture games with one-year-olds, while gradually reducing the device's role. Directors can require vendors to provide straightforward "evidence labels" detailing the product's aims, the studies backing those claims, and the data the device collects. State agencies can support this initiative with small grants for independent, community-based assessments, rather than relying solely on vendor-funded trials. Universities can contribute by standardizing outcome measures and making analysis methods public. The goal is to establish a feedback loop that drives product improvement by facilitating meaningful interactions between adults.

Parents also need clarity in a sea of marketing. A simple guideline can help: if a company cannot provide independent evidence that its product increases human interactions or caregiver responsiveness, view its claims as mere marketing. Another rule: if the device cannot function with most capabilities without an account, internet connection, or broad recording permissions, it is not designed with your child's best interests at heart. These guidelines are practical, not punitive. Babies do not need the latest features. They need consistent prompts that turn everyday moments—like feeding, changing, or bath time—into opportunities for language-rich interactions. The best AI remains in the background and lets human voices take the lead.

Policies can solidify these norms into action. New children's privacy rules in the United States now make it harder to monetize kids' data without explicit parental consent. Europe's AI regulations and the U.K.'s Children's Design Code focus on the best interests and data minimization. Enforcers should prioritize connected toys and baby monitors as early tests; assessments should include code reviews and real-world data analysis, rather than relying solely on checklists. Consumer labels can be helpful, but enforcement is crucial for changing the underlying incentives that drive these behaviors. If companies understand that they must validate their claims and protect their data, products will be developed with a focus on co-play and safety by design, rather than relying on shortcuts for growth.

A Better Ending

Let's return to where we began: a home where a voice assistant is always active and a child is just starting to explore the world. We will not eliminate these devices from our living rooms any more than we removed radios or smartphones from our lives. But we can change their role around babies. We can enforce privacy rules that prevent silent data collection. We can demand proof for both developmental and clinical claims. We can create toys that encourage adults to engage with children rather than interfere with them. We can focus on equity, ensuring that beneficial tools are available first where they are most needed. If one in three households already has a conversational device, the responsible course is to use that presence as an opportunity to deepen human connection, not replace it. The choice is in our hands. Let's develop AI that assists adults in doing what only they can: enriching the early years filled with conversation, touch, and trust.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2024, Feb. 1). Screen time for infants. Retrieved from aap.org.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2024, Feb. 26). The role of the pediatrician in the promotion of healthy digital media use in children. Pediatrics.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2025, May 22). Screen time guidelines. Retrieved from aap.org.

Edison Research. (2024, Mar. 28). The Infinite Dial 2024.

European Commission. (2022, Oct. 27). The EU's Digital Services Act.

European Parliament. (2025, Feb. 19). EU AI Act: first regulation on artificial intelligence.

Grand View Research. (2024/2025). Connected toys market size, share & trends.

Information Commissioner's Office (U.K.). (n.d.). Age-appropriate design code (Children's Code).

Owlet. (2023, Nov. 9). FDA grants De Novo clearance to the Dream Sock. Contemporary Pediatrics.

Romeo, R. R., et al. (2018). Beyond the 30-million-word gap: Children's conversational experience is associated with language-related brain function. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. See also Romeo et al., 2021 review.

University of Basel. (2024, Aug. 26). How smart toys spy on kids: what parents need to know.

U.S. Federal Trade Commission. (2025, Jan. 16). FTC finalizes changes to children's privacy rule.

World Health Organization. (2019, Apr. 24). To grow up healthy, children need to sit less and play more.