Bid Low, Renegotiate Later: Why Education Procurement Must Break the Lowball Trap

Input

Modified

Easy renegotiation encourages lowball bids Costs rise later through change orders while value stays flat Use formula-based indexation, strict correction rules, and transparent amendment data

In Europe, governments spend approximately €2 trillion each year on works, goods, and services, which accounts for roughly 14% of GDP. Suppose even a small portion of that is for education—such as buildings, buses, meals, textbooks, networks, and software—that adds up to around €200 billion through education contracts. A recent study shows that when renegotiation becomes easier, winning bids decrease, renegotiations increase, and total spending goes up, primarily due to large contracts, even though average final prices don’t drop. In education, this means money quietly shifts from classrooms to change orders. Since teacher pay consumes about two-thirds of school budgets, the remaining third is where contracts are. A slight increase in those costs can have a significant impact on learning environments and the equipment students use. The “bid low, adjust later” strategy is not a clever workaround; it is a policy-driven loop that favors insider tactics and sidelines honest approaches. We can change this, but only if we adjust how we assess risk and oversee amendments.

The Lowball Trap Is a Policy Choice, Not a Market Law

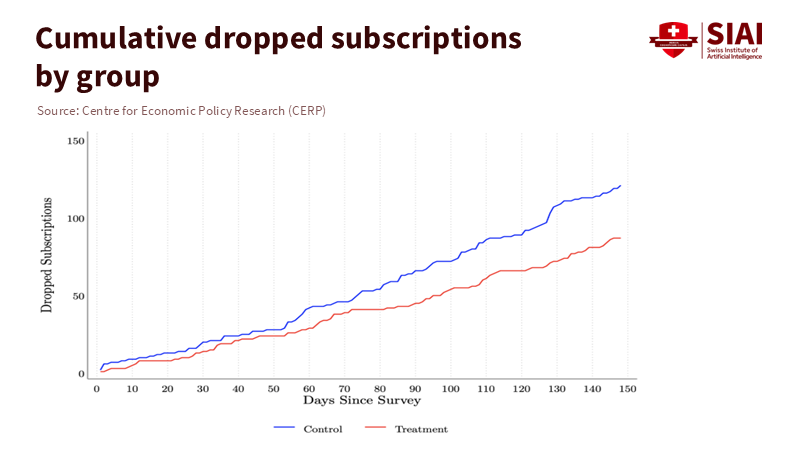

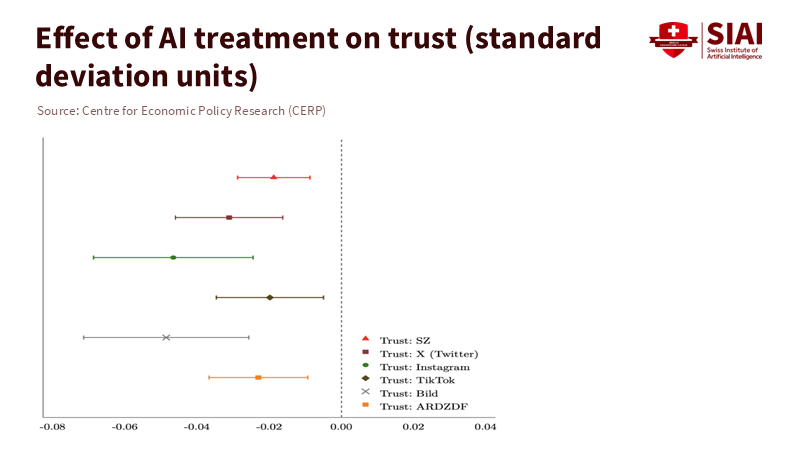

The incentives are simple. When vendors know they can change prices after the award, they underbid initially and plan to adjust prices later. This pattern appears wherever renegotiation is allowed or permitted retroactively. The study mentioned earlier comes from a rule change that lowered initial bid amounts, increased renegotiations, and kept final prices essentially unchanged, while slightly raising overall spending due to a few large contracts. The takeaway for education authorities is clear: allowing easy amendments does not create value; it fosters chaos and wasted time in negotiations. Furthermore, since education contracts are often large and long, the impact of big projects can obscure overall budget management.

Competition is already weakening. EU auditors report a decline in competitive bidding over the past decade, with more single-bid tenders, higher levels of direct awards, and less cross-border competition. When the number of bidders drops, the “lowball then lift” strategy becomes safer because the chances of being undercut by a competitive opponent lessen. Education buyers notice the signs: an increase in “cooperative” or framework purchases that avoid open bidding, retroactive approvals of hefty sums, and informal amendments that shift costs from proposals to the back office. In 2024–25, one large U.S. district approved about $870 million in contracts retroactively after audits indicated process violations, while the UK regulator began investigating potential bid-rigging for school roofing. This does not directly indicate fraud; it reveals a system that makes it too simple to change price discovery from before the award to afterward.

Proponents of easy renegotiation cite fluctuating input costs as justification. They are correct about the volatility. Construction costs surged after 2020; one industry report shows material prices rose almost 40% since February 2020, and steel prices have been unstable, with recent tariffs and energy costs continuing to affect producer prices in 2024–2025. However, volatility does not necessitate unrestricted change orders. Instead, it requires precise, formula-based adjustments that both parties can calculate from day one. When authorities permit broad discretionary amendments—or even retroactive rule changes—strategic underbidding pushes out quality firms that price honestly and cannot afford months of “negotiations” that eat away at their margins.

Method note: to relate the stakes to schools, consider these three facts: public procurement is about 14% of EU GDP; average education spending is around 5% of GDP; teacher compensation accounts for two-thirds of current spending. If we assume conservatively that only one-tenth of procurement targets schools, that translates to roughly 1.4% of GDP being spent on “procured education.” Suppose a relaxed renegotiation rule nudges total spending up by just around 2%, driven by large contracts. In that case, the resource shift amounts to billions each year—money that could fund ventilation upgrades, lab kits, or tutoring. These figures are rough estimates, but they point in the right direction.

Designing Contracts That Price Risk Upfront

The correct approach is not to ban amendments outright, nor is it to allow them indiscriminately. The goal should be to restrict acceptable price movements to those based on precise, symmetric formulas linked to public indices—and to prohibit bespoke “one-off” increases unless they meet narrow, verifiable exceptions. In school construction, this means linking adjustment clauses to transparent, relevant measures, such as the Eurostat construction cost indices or producer price indices for construction materials, and incorporating limits that cap price changes in both directions. Bids should be evaluated on their realistic “index-path price” instead of just the initial figure, and contracts should specify that price increases can also decrease. This internalizes risk and reduces the harmful “race to the bottom” that easy amendments provoke.

Our renegotiation rules should also address timing. The Czech reform’s retroactive element serves as a warning: when rules change retrospectively, they lead to financial problems. Education ministries should enforce a strict ban on retroactive relief; if a shock occurs, relief should apply only to future purchases or stages. Simultaneously, we should enhance upfront realism checks. In a lowball setting, the riskiest bids are not the lowest; they are the weakest with substantial unpriced contingencies. A cost-realism test that evaluates scenarios—like tariffs increasing by 10%, steel dropping by 5%, or labor shortages—will often identify bidders who rely on changing contract terms. When this pattern occurs, make it public: publish the amendment histories of suppliers in a standard format like the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS). Transparency helps maintain integrity and deter misconduct.

Education technology requires a specific solution. Districts now use thousands of tools each year, many sold with vague “pilot-now, scale-later” promises that turn into sole-source renewals at higher prices. The solution is outcome-based contracting with clear evidence checkpoints. If a vendor’s product does not meet a modest, agreed-upon learning-impact target by the second semester, the price decreases or the contract ends without penalties. Three U.S. districts have successfully implemented this approach using cooperative purchasing to keep prices competitive while tying payments to results. This shifts the negotiation focus to designing milestones, rather than back to change orders.

Since competition is our best control, we should also tackle small bidder pools directly. EU auditors warn about an increase in single-bid procedures and high direct awards; the solution in education is to divide large contracts when markets are limited, set realistic timelines, and require efficient “abnormally low tender” evaluations. At the same time, conduct mini-competitions within multi-year frameworks for recurring needs, such as transport routes, device refreshes, or cleaning, so that vendors cannot rely on automatic increases. Lastly, enforce what we publish: bidders who consistently seek extensive amendments should face longer cooling-off periods or have to post amendment bonds. This is not about punishing; it’s about making the “lowball and lift” tactic less attractive than honest pricing.

Method note: volatility is absolute, but it can be quantified. Materials indices show drastic changes since 2020 and ongoing fluctuations in 2024–2025, with tariffs and energy prices affecting steel and other materials. A clause linked to such data—with a clear threshold (for example, ±5%) before adjustments begin—yields predictable, symmetric changes that bidders can assess beforehand. Guides published in 2024–2025 indicate that the market is already heading in this direction; public buyers should follow suit rather than improvising later.

From Bids to Learning Outcomes

Education budgets will tighten in the coming years as aid decreases and other public needs take priority. This makes procurement reform an essential step, not just a regulatory requirement; it’s an intervention in education. Every euro we save by cutting the lowball-renegotiate cycle is a euro available for safe buildings, functional networks, or additional teachers in early grades. The proposed rule changes are straightforward: publish index formulas with the tender, limit discretionary amendments, prohibit retroactive relief, stress-test cost realism before awarding contracts, and make amendment histories publicly available in a machine-readable format. For large purchases, implement structured frameworks with regular mini-competitions to ensure transparency and accountability. For outcome-based purchases, particularly in edtech, link prices to evidence. The goal is to shift negotiations to the beginning, where they belong, while enhancing market engagement to encourage more credible firms to participate.

We should also recognize the counterarguments. Some claim strict amendment rules will deter bidders or result in losses during crises. But evidence indicates the opposite: when renegotiation is too simple, bids may appear lower while value remains unchanged; overall spending can actually rise due to a few large projects inflating their numbers post-award. Others argue that tightening corrections will solidify errors. However, the proven method in public construction allows for narrow, obvious clerical updates while banning subjective “re-pricing.” This preserves integrity without rewarding manipulative practices. In both scenarios, the answer is clarity, not flexibility. If we transparently outline the indices that adjust prices and under what limits, if we publicize vendor amendment records, and if we restrict bid corrections to specific, documented errors, we will attract suppliers who want to compete on the factors that students and teachers experience: safe environments, dependable tools, and effective services.

A final thought. We began with a straightforward observation: a procurement rule that allows renegotiation instead of proper price discovery will, in the end, render the tendering process a mere formality. The solution is to take uncertainty seriously from the start. Practically, this means using formula-based adjustments, banning retroactive changes, establishing clear correction rules, conducting cost-realism tests, and sharing public amendment data. It also means resisting the lure of tempting “savings” at the award stage if the contract is designed to reclaim those savings later. If we implement these changes now, we will enable honest firms to participate, reduce risks on significant projects that impact others, and redirect limited funds toward items that schools need for learning, rather than administrative work. The goal is not to make contracts rigid; it’s to make them fair and predictable. By doing this, we will spend less time renegotiating past decisions and more time creating environments that foster student success and growth.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Associated Builders and Contractors. (2025, Feb. 13). Construction materials prices increase 1.4% in January, up 40.5% since February 2020.

European Court of Auditors. (2023). Public procurement in the EU—Competition remains weak (Special Report 28/2023).

Eurostat. (2025). Construction producer price and construction cost indices: Overview.

Financial Times. (2025, Jul.). U.S. wholesale prices jump 3.3% as tariffs hit the economy.

Gordian. (2025, Aug. 11). What the data says: Steel price updates.

Houston Chronicle. (2025, Jan.–Feb.). HISD contracts and purchasing policy coverage (two articles).

Open Contracting Partnership. (2023). How open is public procurement data in the EU? (Study summary—amendments & implementation fields).

OECD. (2023). Education at a Glance 2023: Indicators in Focus—What do OECD data on teachers’ salaries tell us? (No. 83).

OECD. (2025). Government at a Glance 2025—Government expenditure by function (COFOG). (For education/GDP context).

OECD. (2025). Government at a Glance: General government procurement as a share of GDP (2023 data: ≈12.7%).

Open Government Partnership. (2023). Public procurement: Open contracting basics.

Reuters / AP / S&P Global. (2024–2025). Producer price and tariff-related construction costs coverage.

UK Competition and Markets Authority via The Guardian. (2024, Dec. 11). Inquiry into potential bid rigging for school roofing contracts.

VoxEU/CEPR. (2025). Incomplete contracts and renegotiation in public procurement (evidence from a rule change).

W. Hunter Webb, Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. (2025, May 20). Stop guessing the price—Use material escalation clauses to protect your bid in a volatile tariff climate. (Blog & newsletter).

World Bank & UNESCO (GEM). (2023–2025). Education Finance Watch 2023; GEM data on education finance and aid outlook.

Additional context used: Eurostat construction indices; U.S. PPI materials series; sector commentary on escalation clauses; Digital Promise notes on outcomes-based edtech procurement.