The New Gravity of Japanese Politics

Input

Modified

‘Subliminal learning’ signals spurious shortcuts, not new pedagogy Demand negative controls, cross-lineage validation, and robustness-first training Procure only models passing the worst-case and safety gates across schools

Japan’s July 2025 upper house election delivered a sharp, measurable break with the country’s post-1990s pattern of quiet centrist alternation. A party that held a single seat three years ago won 14 seats and 12.6% of the national vote, powered by a “Japanese First” message and an atypically digital campaign. In the same twelve months, households watched real wages fall repeatedly—even after the most extensive nominal pay hikes in more than three decades—while inflation lingered above the Bank of Japan’s 2% target and the yen flirted with depths not seen since the mid-1980s. Meanwhile, the number of foreign residents reached a record 3.77 million—about 3% of the population—becoming newly visible in neighborhoods short of workers. These facts, taken together, describe a political physics: sustained cost-of-living pressure, rapid and visible social change, and algorithmically amplified grievances, which refers to the use of algorithms in social media to amplify and spread discontent, can tilt even a consensus-oriented polity toward more intricate borders and sharper rhetoric. Japan is not becoming the United States, but it is learning America’s lesson the hard way: when the economy makes people feel small, politics makes someone else smaller.

The economic anxiety engine

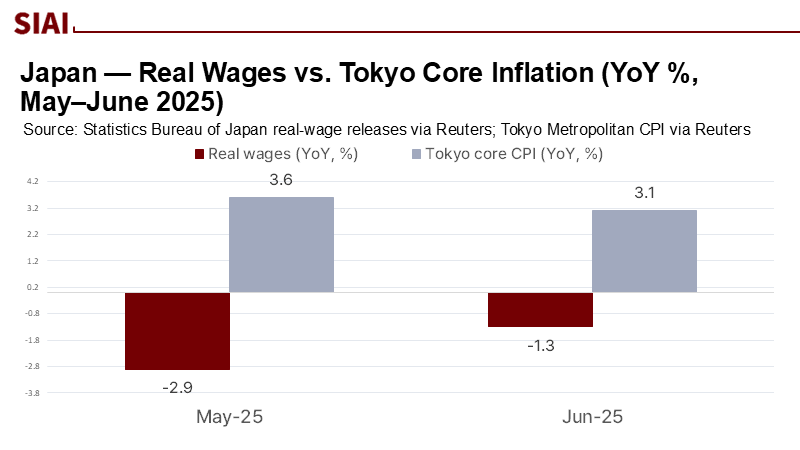

The core conditions of the current cycle are economic, not cultural. Real wages fell 2.9% year-on-year in May 2025 and 1.3% in June, extending a new run of declines even after unions secured average base pay gains of roughly 5.25% at major firms—the biggest in 34 years. In Tokyo, the leading indicator of national price trends, core inflation slowed to 2.5% in August. However, it remained above the target, and the index excluding fresh food and fuel still rose 3%. When headline relief comes from subsidies while underlying prices remain sticky, households feel the squeeze irrespective of macro triumphalism. Add currency strain—the yen’s slide to beyond ¥160 per dollar in 2024–25, prompting intervention—and the sense of diminished purchasing power is both statistical and lived. In this environment, even modest quarterly GDP growth appears abstract, while supermarket prices, electricity bills, and rent are concrete. The literature on post-crisis politics is clear: when recoveries feel uneven and blame appears assignable, the far right’s vote share tends to surge. Japan is not immune to that mechanism.

The household data tell the same story from the kitchen table. In June 2025, average consumption for two-or-more-person households rose 1.3% in real terms year-on-year—a welcome uptick. Yet, the real incomes of worker households fell by 1.7%, underscoring the mismatch between nominal pay packets and everyday costs. These are precisely the conditions in which “who’s to blame?” becomes a more potent question than “what’s the structural fix?” The best global analogue is not the United States’ partisan hardening but the recurring European pattern described by economic historians: after sharp cost-of-living shocks and currency weakness, radical-right parties grow their vote, coalitions fragment, and centrist incumbents absorb parts of the radical agenda to manage the temperature. Japan’s demographics and institutions are different, but the incentive structure is similar. When real wages lag and currency weakness leads to imported inflation, grievance entrepreneurs offer narrative clarity more quickly than technocrats can provide material relief.

Platform populism and the new campaign playbook

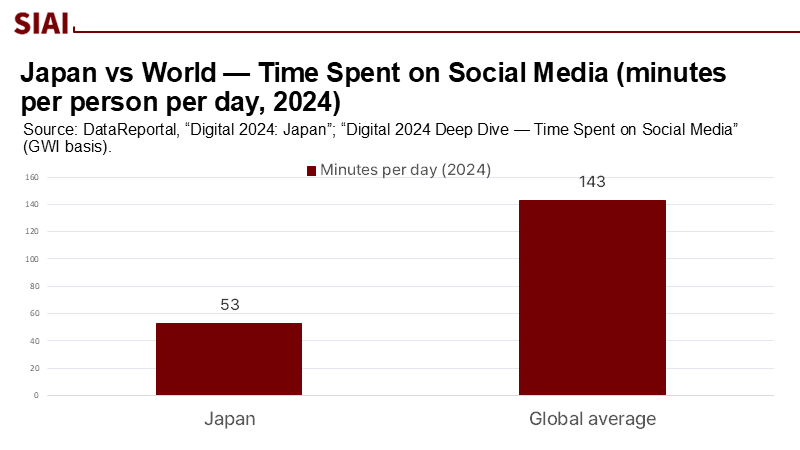

What distinguishes 2025 is not just the message but the medium. Japan formally liberalized online electioneering in 2013; a decade later, a party born on YouTube and refined on LINE and X used those channels to bypass broadcast neutrality rules and monopolize attention among voters disenchanted with legacy media. DataReportal estimates indicate approximately 96 million social media users in early 2024 (roughly 78% of the population), with YouTube’s ad reach alone covering nearly two-thirds of the country. That is not an electoral strategy; it is an electoral substrate. The party’s organisers did not need money for the old machinery of politics because the new machinery—followers, shares, and social media engagement—converts outrage and identity into free distribution. The design choice to foreground algorithmic engagement over deliberation reconfigures what constitutes a “campaign” and who constitutes a “constituency.” In 2025, that asymmetry of reach collapsed Japan’s traditional advantage of low polarisation into something closer to the global norm.

The empirical link between online mobilisation and vote share is notoriously tricky to estimate—a cautious reading pairs platform metrics with election-night data and exit polls. Reuters documented the youth-skewed, YouTube-centered base that propelled the “Japanese First” slate. At the same time, peer-reviewed analysis notes that 14 of 124 contested seats and 12.6% of the vote vaulted a previously fringe party into agenda-setting status —triangulating 18–39 platform-reach estimates with prefectural PR vote shares and turnout (with selection-bias caveats). The bias risk is selection (politically engaged youth are disproportionately visible online), so the stronger inference is qualitative: a low-cost SNS strategy changed the composition of the right, not simply its size, by recruiting politically disengaged, economically insecure voters—especially the “employment ice age” cohort, a group of individuals in their 40s and 50s who have experienced long-term job insecurity.

Immigration anxieties, demographic arithmetic

Immigration is the emotional accelerant in this mix, but the underlying math is demographic. Foreign residents totalled 3.77 million at end-2024—about 3% of Japan’s population—after a 10.5% annual increase. That growth is policy-driven: the country’s chronic labour shortages in care, construction, and hospitality are structurally unfilled from domestic cohorts, pushing successive governments to expand “specified skilled worker” pathways even as the term “immigration” remains politically radioactive. This is a version of a familiar tension: a labour market that needs migrants and an electorate unsure it wants immigration. The gap between economic necessity and cultural comfort is where “foreigner problem” narratives flourish. Officials’ July 2025 creation of a cross-agency body to handle “concerns over foreigners”—in the midst of an election—demonstrates how agenda-setting by a smaller party can pull the centre of gravity rightward, even if most voters rate immigration as a mid-tier concern.

The most responsive audience for that story has been neither students nor retirees but those whom growth repeatedly skipped: the “employment ice age” generation that entered the labour market between the mid-1990s and mid-2000s. Estimates place this cohort at roughly 17–20 million people, who are overrepresented in non-regular work, with weaker pension contributions and thinner buffers against inflation. Decades later, they remain more exposed to price spikes and more sensitive to status threats—and they vote. Here, the cross-national political science is uncomfortably relevant. After financial crises, far-right parties’ vote shares rise by an average of roughly 30%, driven by blame narratives that attach to minorities and outsiders; that pattern is stronger when mainstream parties appear unresponsive. Japan’s political class has historically mitigated that dynamic by emphasising order, consensus, and incremental reform. What changed in 2025 is that SNS campaigning compressed the time between grievance and mobilisation, and a weak real-income environment supplied the accelerant.

Implications for education and policy practice

If the drivers of economic insecurity, visible demographic change, and a media system that rewards emotive frames are present, then the counter-cyclical interventions must be equally practical. For schools and universities, the immediate lever is curricular: embed evidence-based media literacy and a basic understanding of the “political economy of inflation” into compulsory civics, not as an abstract unit, but as a toolkit for reading claims about prices, wages, and “foreigners” that circulate on platforms. Instructional design should emphasize method—how to match a claim to an underlying source, how to distinguish between headline CPI print and core-core inflation, and how to parse a wage settlement from real income when the yen depreciates. Teacher training colleges can model this by co-teaching with local economists and labour-market practitioners. The empirical goal is not to change minds on immigration; it is to raise the baseline comprehension of how cost-of-living math works, so that emotive frames can meet a more literate audience.

For administrators, the relevant unit is the campus and the local labour market. Universities and technical colleges can use short-cycle, credit-bearing programs targeted at the ice-age cohort—weekend upskilling in digital operations, care management, building retrofits—paired with placement agreements that prioritise transitions from non-regular to regular employment. Method note: The expected fiscal multiplier here is small but positive. Pilot programs in prefectures with large stocks of non-regular mid-career workers (estimated from the Labour Force Survey) can demonstrate conversion rates and earnings trajectories over 12 to 18 months. The politics follow the economics: when people experience a credible path out of precarity, scarcity stories lose oxygen. Policymakers can amplify this by indexing targeted subsidies to measured real-income stress (for example, temporary reductions in consumption tax on essential items linked to CPI thresholds) while tightening fact-checking norms in publicly funded media and requiring labelling for synthetic campaign content. None of this will defuse identity politics, but it rebalances incentives away from outrage as the cheapest organising strategy.

Two criticisms are predictable. First, Japan is still “far from US-style polarisation,” so talk of Americanisation is overblown. That is correct in a static sense. However, the warning light is the direction of change: a party with an overtly exclusionary plank has converted digital reach into national vote share and legislative leverage in a single cycle; mainstream parties have already shifted their rhetoric and policy signals on foreign nationals. That is how equilibrium moves—by increments that suddenly add up. Second, that immigration attitudes are more nuanced than headlines suggest. Also true. Surveys show sizable support for accepting foreign workers in sectors with shortages, alongside harsher views toward refugees. The point is not that the public has turned uniformly illiberal; it is that the space for emotive “order” narratives has widened precisely because cost-of-living insecurity makes demand for control more salient. The task for institutions is to narrow that space by reducing the insecurity, clarifying the data, and refusing to outsource civics to engagement algorithms.

A realistic path forward

Japan does not need a constitutional showdown to become less governable; it only requires a few more cycles in which structural economic repair lags perception and social media keeps minting villains faster than policy can mint opportunities. A credible near-term package would knit together three strands: stabilise real incomes (targeted relief and productivity-linked wage compacts), regularise labour-market mobility for mid-career non-regulars (portable benefits, employer incentives for conversion), and inoculate the information space (civics-led media literacy, synthetic-content labelling in campaigns, independent audits of party channels that reach minors). None of this contradicts democratic competition; it disciplines it by lowering the returns to fear-based mobilisation and raising the returns to problem-solving. The goal is not to sideline new parties; it is to force them, and everyone else, onto the terrain of workable answers.

The visible headline of 2025 is a 14-seat shock powered by a smartphone aisle. The less visible headline is that the preconditions for copy-cat cycles remain in place: real wages struggling to keep pace with prices, a currency still prone to importing inflation, and a necessary but poorly explained expansion of foreign labour. We do not need to predict a slide into American-style trench warfare to act as though the risk is real. The lesson of this election is not that Japan is suddenly intolerant; it is that politics will sell reassurance in whatever form people can afford. The assignment for educators, administrators, and policymakers is therefore unusually concrete: teach the math of cost-of-living, rebuild mid-career ladders, and de-glamorise grievance by making progress legible and fast. If we take those steps, the gravity of Japanese politics will tilt back toward confidence rather than scapegoating. If we do not, the cheapest story in the feed—someone to blame—will continue to win seats.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Asahi Shimbun (2024, April 29). Poll: 62% in favor to policy accepting foreign workers.

Bank of Japan / Reuters (2025, January 7). Japan finance minister warns against speculative yen; intervention after 38-year low.

DataReportal (2024, February 21). Digital 2024: Japan.

East Asia Forum (2025, August 31). Takao, Y. Sanseito forces Japan to confront its quiet divisions.

Funke, M., Schularick, M., & Trebesch, C. (2016). Going to extremes: Politics after financial crises, 1870–2014. European Economic Review, 88, 227–260.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (via Reuters) (2025, July 6; August 5). Japan real wages fall again; sixth straight monthly decline.

Nippon.com (2025, March 28). Japan’s foreign population hits 3.8 million.

Reuters (2025, July 20). ‘Japanese First’ party emerges as election force with tough immigration talk.

Reuters (2025, August 28). Tokyo core inflation slows to 2.5%, underlying pressures persist.

Statistics Bureau of Japan (2025, January 24). Consumer Price Index, 2024 annual average.

Statistics Bureau of Japan (2025, August 8). Family Income and Expenditure Survey: June 2025 summary.

We Are Social / DataReportal (2013–2025). Evolution of online campaigning context and platform reach in Japan.

World Economic Forum (2025, July 30). How Japan is boosting its ‘employment ice age’ generation.

Comment