CBAM’s Hidden Race: Why Europe’s Border Carbon Price Is Really an Efficiency Compact

Input

Modified

CBAM sets Europe’s carbon price at the border Asian firms race to cut emissions Europe must share tech and stay efficient

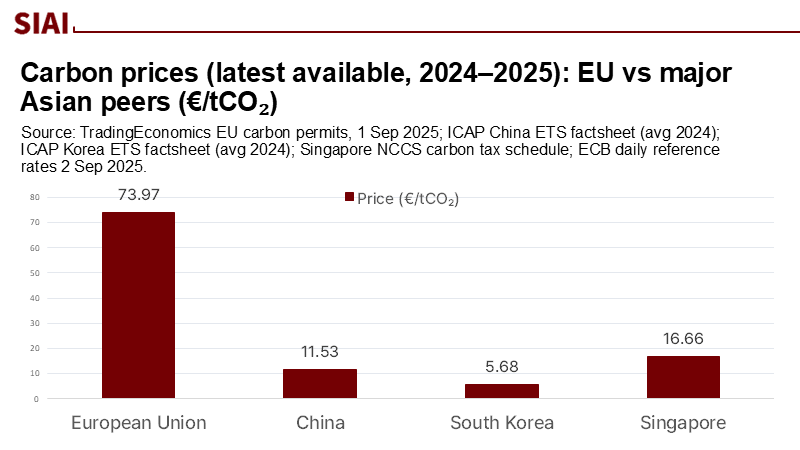

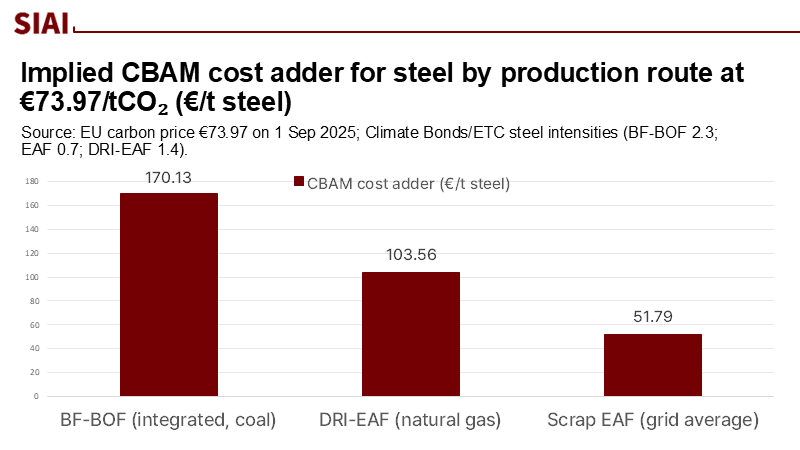

Every few decades, shifts in trade rules alter the competitive landscape. The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is such a shift—not because it taxes carbon at the border, but because it fixes a reference price for industrial efficiency. On January 1, 2026, importers of steel, cement, aluminium, fertilisers, electricity, and hydrogen will begin paying for the embedded emissions of those goods at a rate linked to the EU carbon market, where allowances traded around €74 per tonne of CO₂ as of September 1, 2025. At that price, a tonne of blast-furnace steel with roughly two tonnes of CO₂ embedded would face a surcharge near €150—enough to reorder margins, procurement, and product design across global supply chains.

Europe presents CBAM as a climate measure to prevent “carbon leakage.” Yet its more profound effect is industrial: it sets a moving productivity target that penalizes energy waste and rewards lower-carbon process innovation, regardless of where production is located. Asia’s manufacturers can complain about protectionism; they cannot, if they want to sell into Europe, ignore the yardstick. This is the uncomfortable clarity of CBAM. It is a price that re-weights supply chains toward efficiency—and it will endure long enough to matter, because it is anchored to the phasedown of free EU allowances through the 2030s.

From Border Tax to Industrial Moat

The usual story casts CBAM as a tariff in green clothing. The more realistic reading is that CBAM internalises climate risk while creating an operational moat for producers who move fastest on process efficiency and clean power. Europe’s design deliberately mirrors the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS): in the definitive regime from 2026, importers pay a carbon price aligned with the weekly average ETS auction price, while free allocation to European producers is gradually phased out. That symmetry—price inside the border, price at the border—solves the classic competitiveness objection and, if anything, over time sharpens the incentive to invest in low-emission routes such as scrap-based electric-arc furnaces (EAFs) and direct-reduced iron (DRI) with green hydrogen.

Method note: to get a sense of scale for purchasing and procurement decisions, multiply the embedded emissions intensity of a product by the prevailing EU ETS price. Using a conservative 2.0–2.2 tCO₂ per tonne for integrated blast-furnace steel, the implied border price adder at €74 works out near €148–€163 per tonne before any deductions for carbon pricing paid in the country of origin. That back-of-the-envelope is crude by design; the legal adjustment uses verified embedded emissions and credits for carbon costs already paid. But even this stylised arithmetic clarifies why high-carbon routes will struggle.

The transition costs are not hypothetical. Embedded emissions in EU CBAM imports of 2024 were on the order of 260 MtCO₂e, over half from iron and steel alone. If we apply a €70–€80 range, the gross value of carbon exposure on those flows sits in the tens of billions of euros annually once certificates must be surrendered—costs that could be mitigated only by cleaner processes, cleaner power, or demonstrably lower product-level emissions. CBAM’s transitional reporting through 2025 is precisely to make these numbers real to firms before money changes hands.

Asia’s Counter-Moves and the Rising Floor

It is mistaken to assume Asian producers will sit still. China has expanded its national ETS beyond the power sector to cover steel, cement, and aluminum, bringing roughly 1,500 additional companies and an estimated 3 GtCO₂e into the market. The first compliance dates for the new sectors span 2025–2026, with a free allocation in the initial year, followed by tighter benchmarks. South Korea’s K-ETS remains continent-leading in scope, though prices sagged amid allowance oversupply; Japan’s GX-ETS is voluntary for now but slated to become compliance-based from FY2026; Singapore has already lifted its economy-wide carbon tax to S$25 per tonne in 2024, with a path to S$45 in 2026–2027. Each of these instruments narrows the wedge that CBAM exploits, even if near-term carbon prices in Asia remain a fraction of Europe’s.

The dispersion is stark. Korea’s permits traded in the single digits of US dollars through 2024–2025; China’s national allowance averaged roughly 98 yuan (~€13) in 2024; Singapore’s statutory levy, though rising, is effectively lower for some emissions-intensive trade-exposed firms due to rebates; Australia’s reformed Safeguard Mechanism is tightening baselines by ~4.9% a year with a default compliance unit price around A$36. None of these instruments yet delivers an EU-scale marginal abatement signal. Still, they are moving in the right direction—and, critically, they allow Asian exporters to claim credits against CBAM for domestic carbon costs paid, lowering their net duty at the border.

This shifting policy floor is already catalysing investment. Southeast Asia has become a laboratory for “green steel” plays designed expressly to meet European buyers under CBAM. In Thailand, a new electric-arc furnace project is gearing its output toward the EU market, betting that a cleaner product will command both access and price as CBAM phases in from 2026 to full effect by 2034. The logic is bigger than any one mill: as Europe prices carbon at the border, the cheapest electrons and cleanest routes in Asia turn into a trade advantage—especially where renewables and scrap availability combine.

A Harder Bargain: Efficiency at Home, Technology Abroad

CBAM’s critics call it protectionism with a green gloss. The charge is not baseless—CBAM does, in practice, favour producers already living under a carbon price. But that is not the end of the story. Two policy choices will determine whether CBAM becomes a climate bridge rather than a tariff wall: Europe’s discipline in raising its own industrial efficiency, and its willingness to recycle know-how and some revenues into partner countries’ decarbonisation. Both levers are already visible. The EU’s Innovation Fund is disbursing multi-billion-euro tranches to de-risk industrial decarbonisation and scale new process routes inside the Union. And proposals have emerged to formalise “CBAM-plus” revenue recycling for developing exporters—tying rebates or technology packages to verifiable emissions cuts at source.

Method note: A credible compact would combine three quantifiable tests. First, define product-level benchmarks for embedded emissions trajectories—say, a 5–7% annual decline for steel imports measured at the mill gate. Second, track power-sector carbon intensity in exporter regions, because the greenness of electrons largely dictates the greenness of EAF and DRI routes. Third, publish “CBAM credit” ledgers showing exactly how much of the border payment is offset by domestic carbon costs—under China’s expanded ETS, Korea’s K-ETS, or Singapore’s levy—so the mechanism rewards absolute policy alignment rather than paperwork.

There are also reasons to pace and target CBAM to avoid blunt-force outcomes. The Commission has floated simplifying measures that would exempt most small importers while still covering the overwhelming share of emissions under the scheme—a nod to administrative reality without hollowing out the carbon signal. And industry voices in Europe caution that CBAM alone cannot support a sector like steel; high power prices, overcapacity abroad, and slow demand make a complementary industrial policy unavoidable. CBAM is necessary pressure, but it is not a sufficient strategy.

Seen through the lens of total social cost, the case for keeping the border price uncompromising is straightforward. Climate damages are already macro-relevant: global natural catastrophe losses reached about $318 billion in 2024, with a persistent protection gap; 2023 was the hottest year on record at roughly 1.45 °C above pre-industrial, with extremes battering supply chains. These are not abstract externalities but balance-sheet realities that dwarf the incremental manufacturing costs CBAM will reveal. Paying for embedded carbon is cheaper than paying for systemic climate failure.

CBAM is best understood not as a border wall but as a metronome. It sets the pace at which producers everywhere must reduce embedded emissions to continue selling into Europe. Asia will not be locked out: China’s ETS expansion, Korea’s market, Japan’s GX-ETS, Singapore’s levy, and Australia’s tightening safeguard all point to a rising regional floor that will steadily reduce the net CBAM liability for compliant firms. Europe, for its part, should match a firm external price with internal discipline—cheaper, cleaner power for industry, accelerated electrification of heat, and scaled support for hydrogen-DRI where it truly displaces coal. A practical compact would pair Europe’s relentless efficiency at home with targeted technology transfer and co-financed decarbonisation abroad, including formal channels to recycle part of CBAM’s proceeds into verifiable upgrades of Asian mills and kilns. That is how a tool born of European advantage becomes a global accelerator: by making the price signal unavoidable and the pathway to meet it unmistakable. The most expensive choice now is delay; the cheapest is to compete—on efficiency, on electrons, and on time.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Carbon Brief. (2024, September 23). Explainer: China’s carbon market to cover steel, aluminium and cement in 2024.

Carbon Market Watch. (2024). EU ETS 101—A guide to recent reforms.

CarbonChain. (2025). EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

CO2-IQ. (2025, May 26). EU imports with CBAM tariff in international trade.

Council on Foreign Relations / Reuters / European Commission (news synthesis). (2025). EU considers CBAM exemptions for small importers; coverage of >99% of emissions retained.

European Commission, DG TAXUD. (n.d.). Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (overview & registry).

Fastmarkets. (2025). Evolution of green steel premiums in Europe: flats versus longs.

ICAP. (2023–2025). EU ETS; China National ETS; Korea ETS.

Innovation Fund (CINEA). (2025, March 11 & July 22). €4.2 billion and additional €319 million for industrial decarbonisation projects.

Japan GX-ETS. (2023/2025). Voluntary phase, transition to compliance in FY2026.

Singapore National Climate Change Secretariat. (2025). Carbon Tax—Rates and trajectory.

Swiss Re Institute. (2025). sigma 1/2025—Natural catastrophes.

TradingEconomics. (2025, September 1). EU Carbon Permits—Price.

World Bank. (2025, June 10). State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2025 (and Dashboard).

World Meteorological Organization. (2024–2025). State of the Global Climate 2023; climate indicators at record levels.

Climate Energy Finance & The Energy. (2025, June 5–6). An Asian CBAM—The one tariff the world needs and related report.

Reuters. (2024–2025). Industry reactions and project case studies on green steel; CBAM compliance simplification.

Comment