Tariffs Are a 20th-Century Fix for a 21st-Century Economy

Input

Modified

Tariffs act as taxes, not growth tools Infant-industry logic applies only narrowly Targeted subsidies and workforce policies work better

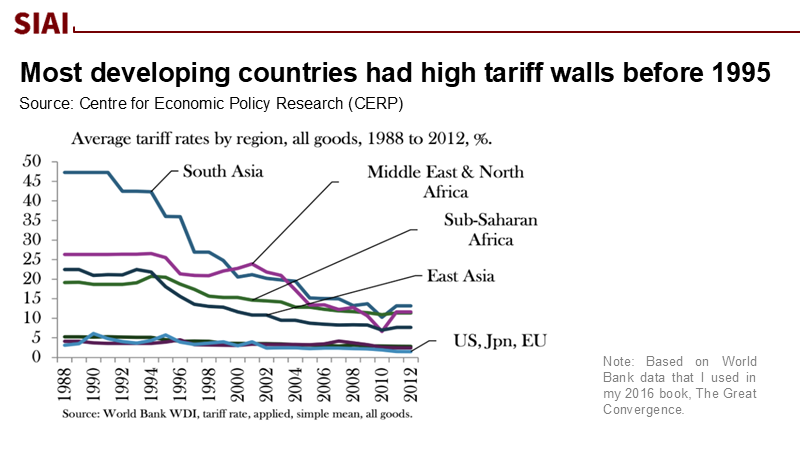

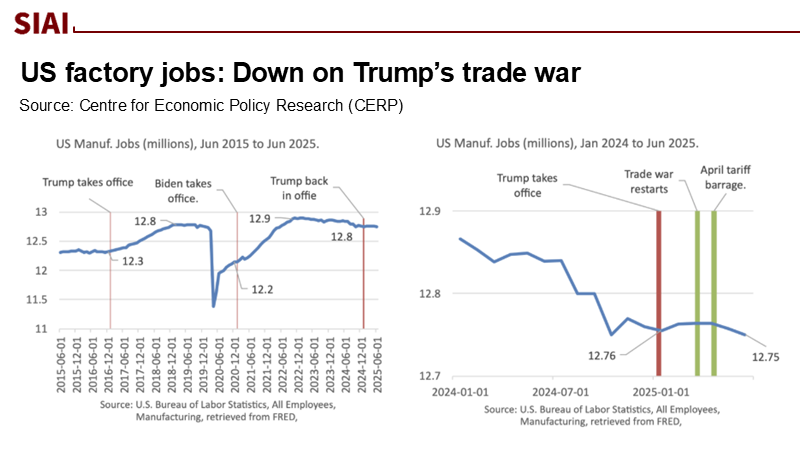

By June 2025, the United States had already collected about $93.9 billion in customs duties this calendar year—more tariff revenue than at any point in modern history, but still only enough to cover roughly 5% of this year’s projected federal deficit. Over the same period, manufacturing employment slid by an estimated 89,000 positions year-over-year, with July alone losing 11,000 jobs. The paradox is stark: higher trade taxes are filling the Treasury while the factory floor continues to thin out. Meanwhile, the structure of U.S. import sourcing is shifting—not toward “Made in America,” but toward “Made near America”—as Mexico overtakes China as the top import partner. Taken together, these datapoints illustrate a fundamental truth that is repeatedly demonstrated in the research: modern tariffs behave like a broad consumption tax, borne mainly by U.S. firms and households, rather than a growth lever that rebuilds complex supply chains. In 2025, we are paying more and producing little of the re-industrialization once promised.

We should reframe the debate by returning to what the infant-industry idea actually argued—and what it did not. The canonical case for protection, from Alexander Hamilton to modern trade theory, was never about propping up mature sectors against comparative-advantage reality. It was a targeted, time-limited intervention to accelerate learning in genuinely young activities where spillovers are significant and under-priced by markets. Hamilton himself favored “bounties”—subsidies—over tariffs; and contemporary welfare-maximizing models show that when protection works, it does so in narrow circumstances characterized by learning-by-doing and dynamic scale effects. None of this describes the broad-brush tariff regimes now in play, which tax a broad consumption base in a highly specialized, services-intensive economy. The right lesson from the past is not import substitution industrialization (ISI) 2.0; it is capability-building where market failures are provable and where the policy instrument matches the failure.

A second reframing is temporal. Industrial policy in a world of long global value chains is not about sprinting to local content; it is about building resilient nodes in networks—human capital, design, and advanced components—that can anchor activity over decades. The U.S. is not a “young country” discovering steelmaking; it is a frontier economy whose comparative advantage lies in R&D-heavy manufacturing niches and knowledge-intensive services embedded in goods. The evidence from 2018 onward is unambiguous: tariff shocks raised prices on targeted goods with near-complete pass-through to import costs, and consumer prices followed. Where reshoring did occur, it was limited and expensive, with notable cases, such as laundry equipment, showing price hikes for both tariffed washers and untariffed dryers as firms exercised their pricing power. This is not the playbook of inclusive manufacturing growth; it is a tax with small fiscal yield and diffuse costs.

The Narrow Gate of Infant-Industry Protection

The infant-industry logic survives scrutiny only under narrow conditions: when a new sector has steep learning curves with spillovers that private investors cannot fully capture; when alternative instruments (like R&D credits, training subsidies, or procurement) cannot as efficiently internalize those spillovers; and when the intervention is explicitly temporary and performance-contingent. Modern theory formalizes this: protection can be welfare-enhancing if dynamic learning externalities are significant and policy is carefully calibrated. Historically, Hamilton’s preferred instrument—bounties—maps better onto today’s targeted grants, tax credits, and milestone-based funding than onto broad tariffs. In 2025, the most defensible “Hamiltonian” efforts are the place-based, time-limited support packages for semiconductors and critical-energy supply chains. These are not ISI walls but sandboxes that reward building capabilities—fabs, tooling, metrology, and especially workforce pipelines—while remaining connected to global demand and technology flows.

Policy details now matter more than slogans. The CHIPS and Science Act appropriates $52.7 billion for manufacturing incentives, R&D, and workforce development, with a specific focus on upstream suppliers and applied research facilities that generate spillovers. Clean-energy credits under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) have catalyzed over $100 billion in announced manufacturing investment, much of it in communities with lower income and lower college completion rates. These instruments embody the infant-industry spirit: they reduce the cost of learning and scaling where private capital under-invests, without taxing the entire import bill. In contrast, broad tariffs on semiconductors or batteries risk raising input costs for downstream U.S. producers, dulling the very competitiveness that subsidies aim to sharpen. The best empirical guidepost remains simple: use precise tools against specific failures, sunset them, and measure learning outcomes along the way.

What 2025’s Tariffs Are Actually Doing

The 2024–2025 tariff actions escalate a pattern that began in 2018: raising statutory rates across strategic categories such as EVs, batteries, solar cells, steel, aluminum, and certain chips. New White House fact sheets and legal advisories outline sharp jumps (for example, EVs from 25% to 100% in 2024), with additional increases staged through 2026. Early-2025 Federal Reserve analysis finds statistically significant pass-through from the latest tariffs into consumer goods prices within months—echoing the 2018–2019 experience where pass-through at the border was nearly complete and retail prices followed. This is why tariff revenues can surge while the inflation impulse looks modest in aggregates: many items are narrow slices of the CPI basket, but for directly affected purchases, consumers pay more almost immediately. The result is a tax wedge that narrows margins for import-reliant small manufacturers and compresses household real incomes at the margin.

On the growth and reshoring question, the scoreboard is mixed at best. While some marquee projects have localized phases of production, the dominant pattern has been diversion and nearshoring. Mexico supplanted China as the top source of U.S. goods imports in 2023 and has extended that lead, consistent with firms re-routing supply chains rather than fully rebuilding them domestically. Kearney’s 2024 and 2025 Reshoring Index reports describe this as a “reality check,” with U.S. demand shifting to nearby sources but limited net repatriation of complex manufacturing. Meanwhile, factory output has been flat in mid-2025, capacity utilization is below long-run averages, and manufacturing payrolls have softened. Tariff revenue is real, but small relative to macro aggregates; it cannot finance a manufacturing renaissance, and its incidence has landed overwhelmingly on U.S. residents. These are the signature footprints of ISI transplanted onto an economy that is neither young nor autarkic.

A Smarter Playbook: Competition, Capabilities, and Conditional Support

If the goal is resilient, economy-wide productivity growth with inclusive labor market outcomes, the policy center of gravity should shift from border taxes to internal capacity, focusing on educators and administrators, which begins with people. Manufacturers report persistent vacancies in mid-skill roles and an expected need to fill millions of positions this decade as processes digitize and the workforce ages. The bottleneck is not tariff protection; it is the pipeline of technicians, mechatronics specialists, quality engineers, AI-assisted maintenance staff, and procurement analysts who can operate in cyber-physical environments. Community colleges, polytechnics, and regional universities should co-design modular, credit-bearing apprenticeships with industry, stackable into applied associate and bachelor’s pathways; state systems should align tuition waivers and completion bonuses to verified competency milestones; and federal aid should reward completion in high-need occupational clusters tied to regionally anchored supply-chain nodes.

For policymakers, the alternative to ISI walls is both Hamiltonian and modern. Use “bounties” where market failures are demonstrable: match-funded R&D and process-engineering grants for supplier qualification; accelerated depreciation and investment tax credits for advanced tooling; and performance-based procurement that pays for delivered capability rather than headcount. Tie each instrument to transparent learning metrics—yield improvements, cycle-time reductions, supplier defect rates, and workforce credential attainment—and sunset support when thresholds are met. Resist blanket local-content mandates that fracture networks; instead, privilege interoperability, open standards, and export orientation so that today’s subsidized node becomes tomorrow’s globally competitive hub. Over time, this approach builds ecosystems that can survive without policy crutches, which is the only meaningful test that infant-industry logic ever proposed.

Finally, we should be candid about costs and sequencing. Tariffs are easy to announce and politically legible; capability-building is slower and often invisible until it compounds. However, the empirical record since 2018 is consistent: broad tariffs have raised prices, generated modest revenue, and done little to expand manufacturing employment or output durably. The most promising results have come from policy instruments that were tightly scoped to address specific learning problems, such as CHIPS-linked workforce and supplier programs or IRA-linked advanced-manufacturing credits. That is a 21st-century reading of Hamilton: buy down the cost of learning, not the cost of foreign goods; build talent and process capability where the United States has, or can plausibly earn, comparative advantage; measure relentlessly; and leave border taxes for narrow, security-critical cases where no other tool fits.

The opening paradox—soaring tariff receipts alongside shrinking factory payrolls—should end any nostalgia for ISI as a general strategy in an advanced, specialized economy. If tariffs were a growth engine, the past seven years would look different: prices would not have jumped so quickly in targeted categories; employment would not be sliding in the very sectors meant to benefit; supply chains would be re-rooting at home rather than detouring to the nearest port of entry. The research record and the 2025 data point in the same direction: tariffs are a tax that buys little industrial capability. The alternative is harder but pays: align subsidies, procurement, and training with provable learning externalities; commit to time limits and metrics; and build globally competitive nodes rather than walls. That is how to make the infant-industry idea fit our century. And it is how educators, administrators, and policymakers can translate an old insight into a modern, durable growth strategy—one measured not by tariff revenue, but by the capabilities Americans actually acquire.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Amiti, M., Redding, S. J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2019). The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on U.S. Prices and Welfare. NBER Working Paper No. 25672 / AEA Papers & Proceedings 110 (2020): 541–546.

Baldwin, R. (2025). Trumpian tariffs are import-substitution industrialisation 2.0. VoxEU/CEPR.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025). The Employment Situation—July 2025; CES Highlights.

Cavallo, A., Gopinath, G., Neiman, B., & Tang, J. (2020/2021). Tariff Pass-Through at the Border and at the Store. AEA Papers & Proceedings / IMF Working Paper.

Customs and Border Protection (CBP). (2025). Trade Statistics: Total Duty, Taxes, and Fees Collected.

Federal Reserve Board. (2025). Detecting Tariff Effects on Consumer Prices in Real Time (FEDS Note).

Federal Reserve. (2025). Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization—G.17.

Fajgelbaum, P. D., Goldberg, P. K., Kennedy, P. J., & Khandelwal, A. K. (2020). The Return to Protectionism. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(1), 1–55; working paper versions 2019–2021.

Kearney. (2024–2025). U.S. Reshoring Index (2024 report; 2025 “Great reality check”).

Melitz, M. J. (2005). When and How Should Infant Industries Be Protected? Journal of International Economics. (Working paper version).

National Association of Manufacturers (NAM). (2025). Facts About Manufacturing. (Employment trends; long-run workforce needs).

U.S. Census Bureau. (2025). Top Trading Partners—December 2023 (annual totals).

U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2023–2024). Inflation Reduction Act manufacturing investment press releases and guidance.

U.S. NIST (CHIPS for America). (2024). Federal Programs Supporting the U.S. Semiconductor Supply Chain and Workforce (Fact Sheet).

White House (Archived). (2024, May 14). Fact Sheet: President Biden Takes Action to Protect American Workers and Businesses from China’s Unfair Trade Practices.

White & Case. (2024, May 15). Biden Administration Expands Section 301 Tariffs on Imports from China.

Comment