SEATO 2.0: A Southeast Asian Shield, Not an “Asian NATO”

Input

Modified

Southeast Asia needs a maritime compact, not an Asian NATO Prioritize shared surveillance and coast-guard rules Outside partners support; ASEAN states lead

The most consequential number in Indo-Pacific security is not a missile range or fleet tonnage but a trade figure: roughly one-third of the world’s seaborne commerce transits the South China Sea each year, carrying on the order of trillions of dollars in goods through narrow straits and contested waters that connect Southeast Asia to the global economy. The CSIS ChinaPower project’s route-by-route estimation places the 2016 value at nearly $3.4 trillion; with the share of maritime freight from developing economies rising to 54 percent by 2023, the absolute exposure today is even larger—although precise estimates vary by method. The point is scale: an interruption measured in days would ripple through energy markets, manufacturing schedules, and food prices from Manila to Mombasa. That exposure has grown alongside defense spending across Asia and Oceania, amid a drumbeat of dangerous gray-zone confrontations, such as those at Second Thomas and Scarborough Shoal. The region needs collective protection commensurate with the stakes, but it does not require an “Asian NATO.” It needs a purpose-built Southeast Asian shield.

Why a Pan-Asian NATO Won’t Work

A trans-regional alliance, modeled after NATO, founders on politics before it reaches force structure. Southeast Asia’s security preferences are heterogeneous by design: some states are U.S. treaty allies, some hedge their bets, some are closely tied to Beijing, and all prize autonomy and ASEAN centrality. That is why senior officials in Manila—despite bearing the brunt of gray-zone coercion—have themselves dismissed the feasibility of a NATO-style bloc in Southeast Asia for now, citing divergent interests and entanglements in alliances. NATO has expanded its dialogue with Asia’s “AP4” (Japan, the Republic of Korea, Australia, and New Zealand). Still, this outreach highlights the core problem: the Indo-Pacific is already densely interconnected with bilateral and minilateral links whose logics often conflict. An “Asian NATO” would either duplicate them at significant diplomatic cost or collapse under its own weight.

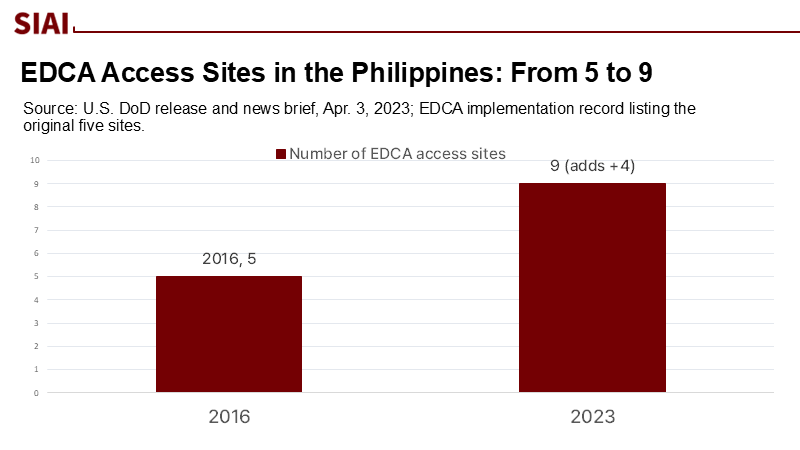

The operational picture reinforces the political one. The most acute frictions are not classical invasions but calibrated coast-guard and militia actions that inflict bodily harm and material damage while slaloming below the threshold of war. Incidents during 2024–2025—from collisions to water-cannoning—are paradigmatic: they require shared maritime domain awareness, codified rules for law enforcement vessels, and interoperable crisis management, as much as they require frigates. By contrast, a pan-Asian mutual-defense clause would be a poor tool for deterring “white-hulled” coercion and an even poorer fit for ASEAN members that resist binding security guarantees with great-power militaries. What has advanced in recent years is not a mega-alliance, but a lattice: enhanced U.S.–Philippine basing access under EDCA (from five sites to nine) and updated bilateral defense guidelines that outline how treaty obligations apply at sea. Those are useful strands—but they are not, and should not become, a continent-spanning NATO analogue.

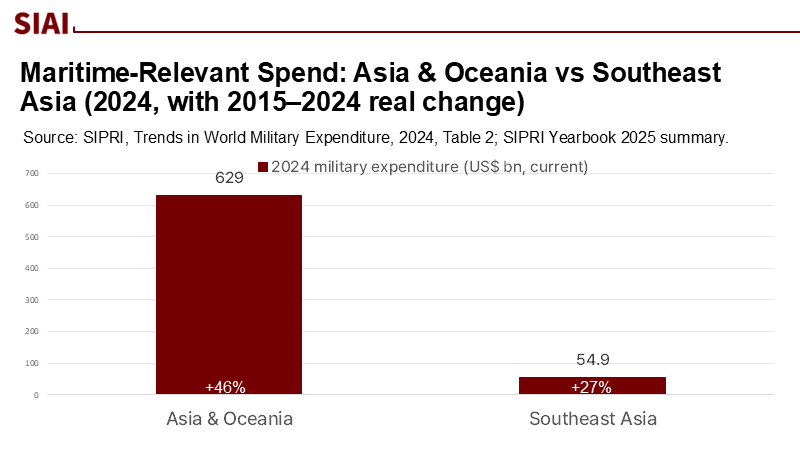

The analogy to Europe after 1949 is also overdrawn. NATO emerged to deter a singular, armored threat to a continent carved by wartime occupation and divided by an iron curtain; its Article 5 was the backbone of a U.S. troop presence keyed to that scenario. Asia’s threat surface is broader and more maritime; the rivalries are multiplex, and the political geography is radically different. Even NATO’s evolving agenda recognizes that its Indo-Pacific role is supplementary—encompassing cyber, disinformation, and economic coercion—not the framework for war-and-peace decisions in Asian littorals. More importantly, steep increases in global and regional defense spending have not produced consensus on who should fight for what, where. That is precisely why the answer in Southeast Asia must be sub-regional, maritime-first, and legally grounded rather than ideologically bloc-based.

Reanimating SEATO as a Southeast Asian Shield

History offers both a template and a warning. The original Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was established in 1954 to contain communism but ultimately failed in 1977, having never developed an integrated command, standing forces, or an automatic defense obligation. It functioned more as a political umbrella and U.S. rationale in Indochina than as a genuinely Asian collective-defense mechanism. Those are instructive design flaws, not an epitaph for the idea of a Southeast Asian security compact. The lesson is to invert the old model: make it operational first and political second, maritime first and military-strategic second, Southeast Asian in membership but open to structured support.

A “SEATO 2.0” would not be an alliance pledging instant warfighting. It would be a treaty-backed, crisis-ready regime that hardens the maritime commons against coercion. The legal framework already exists in UNCLOS and in the 2016 arbitral ruling, which rejected expansive historic rights claims and censured unsafe law enforcement practices. Building on that spine, a revived SEATO should formalize three core obligations among Southeast Asian signatories: to share a common operating picture of their maritime zones; to adopt harmonized rules of engagement for coast-guard and auxiliary vessels; and to coordinate legal and diplomatic responses—including sanctions-like measures—when one member’s sovereign rights are violated. None of these requires a collective-war pledge; all of them raise the costs of gray-zone tactics by shortening the time between incident, evidence, and consequence.

For credibility, the regime must be resourced. Here, the macro numbers matter. World military spending reached $2.44 trillion in 2023 and is projected to reach $2.72 trillion in 2024; Asia and Oceania’s share is expected to rise to roughly $629 billion in 2024, up 46 percent from 2015. Those aggregates are not a call for an arms race; they are an argument for reallocating marginal dollars toward the public goods that make deterrence effective—persistent surveillance, quick-reaction law enforcement presence, civil-military communications, and post-incident legal capacity. Treat the ocean as a single operating environment, not a set of stovepiped sectors.

From Concept to Capability: A Practical Roadmap

The Quad’s Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA) integrates commercial satellite, radio-frequency, and AIS data to identify “dark” vessels and illegal maritime activities. A SEATO 2.0 initiative could enhance this framework for Southeast Asia by creating a jointly governed operating picture with regional tasking and privacy protocols. This would involve extending unclassified data feeds to a SEATO portal, standardizing data labeling for various maritime centers, and setting thresholds for automated alerts concerning suspicious activities, such as militia massing in member countries' Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). Additionally, a SEATO code of conduct should address incidents involving coast guards in Southeast Asia's gray-zone operations. It would define engagement protocols and involve state-directed auxiliary maritime militias. Incorporating camera systems on law enforcement vessels with secure timestamps would allow for real-time evidence collection.

Moreover, to deter violations effectively, a SEATO 2.0 should implement a "violation ladder" that triggers immediate collective actions, such as joint diplomatic initiatives and coordinated legal responses, ensuring a clear framework for accountability rather than vague mutual defense commitments. This approach necessitates a focused sanctions toolkit aimed at non-compliant foreign vessels and entities, ensuring impactful consequences without broad economic retaliation.

Fund essential aspects of maritime security in Southeast Asia through a pooled maritime-security fund, financed by modest percentages of rising defense budgets. This could support coastal radar upgrades, satellite access, training for maritime prosecutors, and interoperable coast guard radios, enhancing reaction times and stability without inciting fears of militarization. Maintain a Southeast Asian membership while introducing an outer ring of “adjunct partner” status for Japan, India, Australia, and the U.S. This preserves regional agency while leveraging their capabilities for data sharing, capacity-building, logistics, and joint exercises focused on law enforcement.

Integrate initiatives with ASEAN through the ADMM-Plus framework, enabling a revitalized SEATO to implement maritime security measures while maintaining ASEAN centrality. This balances action and discussion, welcoming states that prefer to observe before joining. Establish clear deadlines for progress in the ASEAN–China code of conduct negotiations. A revived SEATO could implement a two-year plan: year one for treaty ratification and data harmonization, and year two for practical exercises focused on reaction times and severity rather than treaty perfection.

Concerns that a tighter Southeast Asian compact might provoke rather than stabilize can be addressed through design. A maritime law-enforcement-first regime based on UNCLOS offers clear off-ramps—such as evidence-based attribution, proportionate responses, and hotlines—before escalation occurs. This framework avoids mutual-defense clauses, enabling Southeast Asian states to maintain their sovereignty while strengthening their collective interests. For external partners, this approach builds lasting institutions rather than relying on temporary military support.

The critique that reviving “SEATO” brings Cold War baggage can be mitigated by limiting its scope and focusing on Southeast Asian membership. The brand matters less than the behaviors and capabilities it fosters. If necessary, rename it the Southeast Asian Maritime Security Compact; what’s important is that it exists, is funded, and is effectively utilized.

From Shipping Lane to Security Lane

Return to that opening statistic and what it implies. A region that carries a third of the world’s seaborne trade cannot rely on ad hoc coalitions or perpetual “talks about talks”. At the same time, water cannons continue to injure crews and collisions erode fiberglass and diplomacy alike. The financial means are available—regional defense budgets are proliferating—but money without a disciplined, law-anchored design will not guarantee safety. The correct answer is not a sprawling “Asian NATO” that would import the politics of faraway alliances into Southeast Asian waters. The correct answer is a Southeast Asian shield that monitors the sea in real-time, codifies conduct where coercion actually occurs, and converts outrage into rapid, collective, legal consequences. Build that over the next twenty-four months, and the South China Sea becomes harder to bully and easier to manage. Fail, and the world’s most valuable shipping lane remains the world’s most under-governed flashpoint. The choice, and the opportunity, belong to Southeast Asia.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). “ADMM-Plus: About.” 28 Apr. 2025.

Council on Foreign Relations. “Does NATO Have a Role in Asia?” 30 May 2024.

East Asia Forum. “Asia must learn from SEATO and build its own NATO.” 27 Aug. 2025.

Ministry of Defence, Singapore. “FY2025 Budget Estimates” and related statements, Mar. 2025.

Permanent Court of Arbitration. The South China Sea Arbitration (Philippines v. China), Award, 12 July 2016; case materials 2013–2016.

Quad Leaders/Embassies of Australia, India, Japan, United States. “Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness (IPMDA) Fact Sheets,” 2023–2024.

Reuters. Multiple reports: “NATO-type Southeast Asian security group not feasible, Philippines minister says,” 5 Nov. 2024; “China and the Philippines trade accusations over collision,” 17 Jun. 2024; “Philippines accuses China of damaging its vessels,” 30 Apr. 2024; “Philippines grants U.S. greater access to bases,” 2 Feb. 2023; “ASEAN–China code of conduct talks,” 2024–2025.

SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute). Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2023 (Fact Sheet), 22 Apr. 2024; Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2024 (Fact Sheet), 28 Apr. 2025.

U.S. Department of Defense. “U.S.–Philippines Bilateral Defense Guidelines,” 3 May 2023; “Locations of four new EDCA sites,” 3 Apr. 2023.

U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian. “Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), 1954” and FRUS documents on SEATO dissolution.

UNCTAD. Review of Maritime Transport 2023 (and 2025 statistical release on maritime trade shares).

Wilson Center. “Southeast Asia Maritime Security and Indo-Pacific Strategic Competition,” Policy Brief, 13 Mar. 2025.

Comment