Tariffs Don't Hire: Why Input Taxes Shrink Factory Payrolls in a Networked Economy

Input

Modified

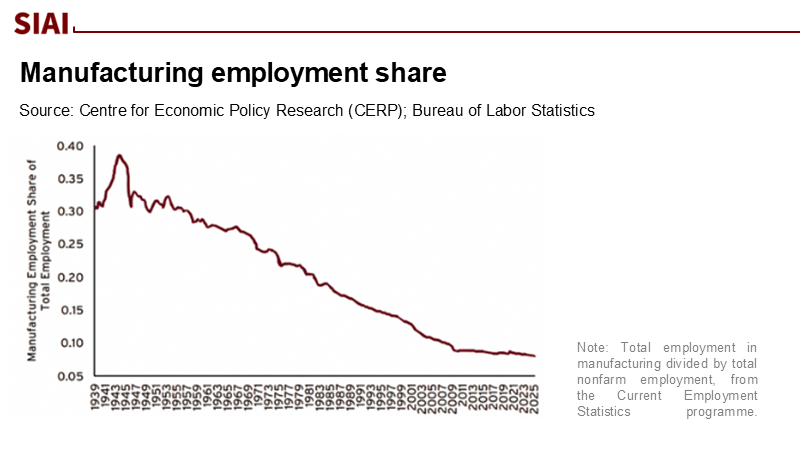

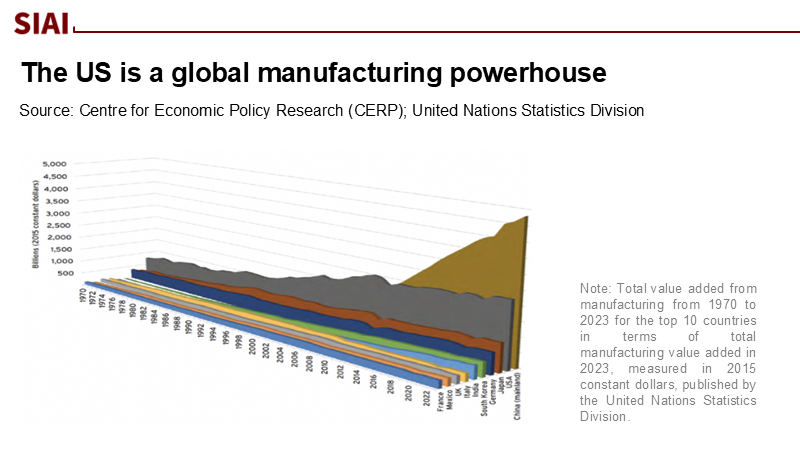

Tariffs framed as job protection often act instead as taxes on critical inputs Employment in U.S. manufacturing has remained flat even as output and global share stay strong Lasting job growth requires investment in supply chains, not higher barriers at the border

In July 2025, U.S. manufacturing employment stood at 12.727 million jobs, nearly the same as before the recent tariffs implemented in April and July. Despite the narrative surrounding "reciprocal" and sector-specific tariffs, factory hiring has not shown a consistent increase. The tariffs include a 10% baseline tax on most imports, effective as of a national emergency declared on April 2, 2025, with adjustments made in July. If tariffs effectively boost employment, payroll statistics would reflect this shift, but they do not. This highlights the key argument: in an economy reliant on foreign inputs and essential minerals, tariffs act as input taxes that raise costs, increase prices, reduce demand, and ultimately lower payrolls instead of expanding them.

Reframing the Claim: From "Infant Industry" to "Input Chains"

Classic protectionism rests on an intuition: shield domestic firms from foreign competition, and they can scale, learn, and hire more effectively. That logic presumes a production frontier contained mainly within national borders—an era when finished goods were stitched, stamped, or machined end-to-end at home. Today's manufacturing relies on multi-country networks, where imported components, sub-assemblies, and critical materials are integrated into nearly every product category, ranging from autos to appliances to clean tech. The policy question, rephrased for 2025, is not whether tariffs can tilt the outcome of a head-to-head contest between a domestic and a foreign producer. It is whether tariffs, applied to inputs, can expand employment in domestic plants that depend on those inputs. The burden of evidence cuts against that hope. The most recent summaries of research on the 2018–2019 trade war find near-complete pass-through of tariffs to U.S. import prices and consumer prices, muted output gains in directly protected sectors, and losses downstream where higher input costs are passed on—exactly where the jobs are. In short, infant-industry stories do not travel well into input-intensive supply chains.

What the Latest Data Actually Shows

Two empirical anchors matter now. First, the headline: U.S. manufacturing employment was 12.727 million in July 2025, remaining little changed in the months following the universal 10% tariff's effect on April 5 and after July's further modifications. Second, the broader scholarly record—from firm-, industry-, local labor market-, and macro-level studies—finds that the 2018–2019 tariff round, which refers to a period of increased tariffs and trade tensions between the U.S. and its trading partners, did not deliver net manufacturing job growth; instead, it raised input costs and invited retaliation that suppressed exporters' labor demand. That pattern is mirrored in 2025 policy design: a baseline tariff layered on top of targeted hikes that the prior administration finalized in 2024 for strategic categories such as EVs, batteries, semiconductors, and solar. The composition matters because these categories sit at the junction of deep, global supplier webs; taxing them ripples through domestic producers and consumers alike. If recent history is a guide, the jobs ledger will tilt negative once pass-through and retaliation are netted against any local gains in highly protected niches.

How Tariffs Hit Where It Hurts: Inputs First, Payrolls Next

Mechanically, tariffs raise the delivered cost of imports. In an input-dense system, this refers to an input tax. Studies of the 2018–2019 tariffs consistently estimate a pass-through rate of nearly 100% to U.S. import prices and a substantial pass-through to retail prices. 'Pass-through' in this context refers to the extent to which the cost of the tariff is passed on to the consumer in the form of higher prices. The U.S. International Trade Commission's 2023 congressionally mandated review found that while protected sectors achieved small production gains, downstream sectors faced higher costs and slightly higher prices, resulting in overall U.S. welfare losses and no aggregate job dividend. For 2025, consider a transparent back-of-envelope calculation: the OECD's TiVA framework shows the foreign value added embedded in U.S. manufacturers. Even a conservative 15–20% foreign content share implies that a 10% baseline tariff adds roughly 1.5–2.0% to input costs before targeted surcharges. With unit labor requirements roughly fixed in the short run, higher input costs push up final prices. If demand elasticity in these categories is near one in absolute value—a common finding—then a 2–4% price increase trims volumes by a similar percentage. At typical output-per-worker levels, that arithmetic threatens jobs in input-exposed plants faster than it creates them in protected ones.

Supply Chains We Actually Have: Critical Minerals and Strategic Bottlenecks

Even if tariffs were neutral on average, they collide with a separate constraint: the United States cannot yet substitute away from many foreign inputs that sit at the heart of modern manufacturing. China maintains its dominant position in processing heavy rare earths and producing rare-earth magnets, which are essential to automobiles, wind turbines, and defense systems. In April 2025, Beijing tightened export licensing on seven rare earths and magnets in response to U.S. tariff escalation, further complicating access. U.S. investments are underway—from Mountain Pass to new magnet facilities—but volumes remain a fraction of Chinese capacity, and the separation and refining steps are precisely where non-Chinese capacity is thinnest. When a tariff shock hits a bottlenecked supply chain, it magnifies the scarcity premium rather than nudging an easy substitution to domestic sources. That is not a recipe for sustained factory hiring; it is an invitation to delay capital expenditures, trim output, or pass costs through to consumers until demand picks up.

The Automaker Case: Prices Up, Forecasts Down

Automobiles are a clean test because they sit atop long, international supply chains and sell into highly elastic consumer markets. In late August 2025, Mitsubishi Motors cut its full-year operating profit forecast by 30%, explicitly citing the impact of U.S. import tariffs and the need to raise sticker prices and cut incentives to defend margins. That is the textbook transmission of input taxes into retail prices. It has second-order effects: higher prices choke off sales, domestic dealerships reduce hours and headcount, and U.S. plants supplied by tariff-hit parts face weaker run-rates. In theory, tariffs reinsource parts production. In practice, the time to retool, re-permit, staff, and qualify suppliers is measured in years, not quarters; credit conditions and policy uncertainty compound delays. Auto illustrates the broader point: when tariffs lift the cost of the typical car by a few percent in a market where buyers can postpone purchases or trade down, unit volumes fall, and employment follows volumes—not slogans.

Where Tariffs Might Work—and Why Those Cases Are Narrow

There are corners of the economy where tariff-assisted hiring could occur, such as products with short supply chains, low foreign input content, and ready domestic capacity, or sectors with strong procurement-led demand that can absorb price increases, like defense or certain medical goods. Here, tariffs operate more like a procurement preference layered on top of steady orders, dampening import competition without starving domestic producers of critical intermediates. But even these cases are bounded. Many "strategic" goods—EV batteries, semiconductors, specialized machinery—are precisely where foreign input content is highest, where learning curves are steep, and where critical minerals are bottlenecked. For these, tariffs can at best buy time for complementary industrial policy to stand up domestic links; on their own, they cannot conjure the missing tiers of suppliers, engineers, and permitting approvals. The 2024–2026 escalators on EVs, batteries, solar cells, and semiconductors illustrate the tension: the more targeted the tariff, the deeper it reaches into complex inputs.

A Better Policy Mix: Tax Inputs Less, Invest in Capacity More

If the objective is to secure factory jobs, the policy lever should be the unit cost of domestic production, net of uncertainty—not the gross cost of imported inputs. Three design pivots follow from the evidence. First, exempt or rebate tariffs on bona fide intermediate goods used in U.S. production through expanded, automatic duty-drawback and suspension programs, thereby minimizing the "tax on investment" problem that researchers identified during the last trade war. Second, pair narrow, time-bound final-goods tariffs with large-scale, rules-based subsidies that move learning curves—accelerated depreciation for process equipment, production tax credits for upstream inputs, and predictable public procurement that validates scale. Third, target the true chokepoints by financing domestic refining and the separation of critical minerals, as well as fast-tracking permitting for midstream plants, where public investment and regulatory certainty can catalyze private capital expenditures. These instruments lower the cost of manufacturing in America without betting the payroll on raising the cost of buying parts from elsewhere.

Anticipating the Pushback

The case for tariffs today is framed in three registers: fairness, security, and resilience. Fairness claims that reciprocity is owed; security warns of dependence on adversaries; resilience promises shorter, sturdier chains. These are legitimate concerns. However, the channel through which general tariffs address them is weaker compared to targeted tools. Reciprocity arguments can be pressed through negotiated sectoral deals and WTO-consistent enforcement without taxing every input a U.S. firm needs tomorrow morning. Security vulnerabilities in critical minerals and munitions are real; they will not be solved by making inputs more expensive before domestic capacity is established. Resilience is best built through redundancy, inventory buffers, and diversified sourcing, rather than by raising the price of every imported component regardless of risk. The empirical record from 2018–2019, the payroll flatline in 2025, and the immediate price responses in autos underscore a typical lesson: tariffs that ignore input realities dilute fairness, impair security, and slow resilience by eroding the cash flows needed to invest in the very capacity we say we want.

The Price Tag of Make-Believe Protection

The fundamental principle of contemporary protectionism is emotionally appealing but economically lacking. If imports pose a danger, impose taxes on them; if factories feel vulnerable, offer them protection. However, the items being taxed are wires, wafers, magnets, chemicals, and stamped parts—the essential components of American manufacturing. Within that context, tariffs function more as an extra expense in production rather than a protective barrier, leading to corresponding reactions in the labor market. The employment statistics from 2025 so far show no noticeable increase in hiring as a result of broad tariff policies. The prevailing research from the previous trade conflict is clear: complete transfer to consumer prices, minimal gains for the protected sectors, more significant losses downstream, and no overall job growth. Key material supply chain limitations indicate that finding substitutes will take years, not just a few quarters. An effective employment strategy should focus on reducing taxes on inputs, mitigating investment risks, and directing public funding toward the obstacles that hinder domestic scale. Unless policy aligns with our actual manufacturing processes, the assertion that tariffs will "bring jobs roaring back" will remain as empty as an unfilled order book.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Amiti, M., Redding, S. J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2019). The impact of the 2018 tariffs on prices and welfare. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 187–210. Retrieved from the American Economic Association.

Atlanta Fed Policy Hub. (2025). Tariffs and consumer prices (Policy Hub No. 2025-01). Summarizes evidence of near-complete pass-through from the 2018–2019 trade war.

CEPR VoxEU. (2025, August 26). Strain, M. R., The (non) effect of tariffs on manufacturing employment. Synthesis chapter arguing tariffs are likely to reduce, not increase, factory jobs.

CSIS. (2025, April 14). Baskaran, G., & Schwartz, M., The consequences of China's new rare earths export restrictions. Details new licensing controls and U.S. capacity gaps.

OECD. (2023 edition). Trade in Value-Added (TiVA) database (coverage to 2020). Concept and indicators on foreign value added in manufacturing exports and domestic final demand.

Reuters. (2025, August 27). Japan's Mitsubishi Motors cuts full-year operating profit forecast by 30%, citing U.S. tariffs and planned price hikes/incentive cuts.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED. (2025). All Employees, Manufacturing (CES3000000001) — July 2025 level: 12.727 million.

U.S. International Trade Commission. (2023, March 15). Economic impact of Section 232 and 301 tariffs on U.S. industries (Pub. 5405). Finds reduced Chinese imports, small production increases in protected sectors, higher prices downstream, and net welfare costs.

U.S. International Trade Commission. (2023). Section 301 tariffs (summary page). Notes estimated aggregate effects (imports from China −13%, U.S. production +0.4%, U.S. prices +0.2%).

USTR. (2024, September 13). USTR finalizes action on China tariffs following statutory four-year review. Confirms hikes in strategic product categories and implementation timing.

Utility Dive. (2024, September 16). Biden finalizes China tariff hikes, including for EVs, batteries, and solar panels—EVs to 100%, batteries 25%, solar cells 50% (with semiconductors at 50% in 2025).

White House. (2025, April 2). Fact sheet: President Donald J. Trump declares national emergency… Announces a universal 10% reciprocal tariff baseline with effective dates.

White House. (2025, July 31). Executive action: Further modifying the reciprocal tariff rates. Details trading-partner-specific adjustments and ongoing authority under IEEPA.

Comment