When Memory Misfires: Why Teaching the Last Crisis Risks Slowing the Next Recovery

Input

Modified

Misapplied memories of past crises distort investor behavior and delay recovery Overshooting stems less from ignorance than from faulty analogies that amplify panic or euphoria Policy should focus on structural safeguards and qualified capital, not generic history lessons

In March 2023, depositors withdrew $42 billion from Silicon Valley Bank in a single business day—more than double the amount that caused Washington Mutual's collapse in 2008, but occurring within just one trading session instead of over sixteen days. Regulators identify a new trio of factors contributing to this: uninsured, interconnected deposits; social media that accelerates the spread of rumors; and "always-on" digital platforms that allow fear to translate immediately into actions. The Financial Stability Board's 2024 review cautioned that technology and online frameworks can amplify the speed of bank runs, surpassing the assumptions built into traditional liquidity regulations. Responding to a contemporary crisis as if it were 2008—characterized by mortgage defaults and long lines at bank branches—fails to understand the situation accurately. The issue isn't a lack of historical knowledge; it's the inappropriate history that leads to misguided reflexes. When policymakers, businesses, and households cling to past comparisons, they risk exacerbating the excessive reactions that delay recovery. Memory does not serve as a protective barrier. If mishandled, it becomes a catalyst for problems.

From "Fixing Memory" to "Fixing the Analogy": Reframing the Policy Problem

The familiar prescription after turmoil is to remind investors what happened last time—an earnest attempt to correct biased beliefs by teaching the past. But the empirical puzzle of 2023–2024 is that many actors did remember; they remembered the wrong crisis. Balance-sheet losses and interest-rate risk mattered, yet the fastest runs clustered where business model narratives and network structure made panic more contagious, even when the balance-sheet red flags were not the largest. A 2025 Chicago Fed analysis argues that focusing solely on unrealized losses and uninsured deposits misses the reason why certain banks unraveled while others with similar metrics did not: investors mapped 2008-style fragilities onto institutions whose real vulnerability was a brittle model combined with hyper-mobile funding. In financial markets, memory travels as an analogy, and analogies can be misleading. The policy task, then, is not to saturate retail and professional investors with more history, but to curate which historical patterns apply to today's regime and which do not—especially in markets with lower collective financial literacy where analogies are more likely to be taken literally.

How Memory Distorts Prices and Flows

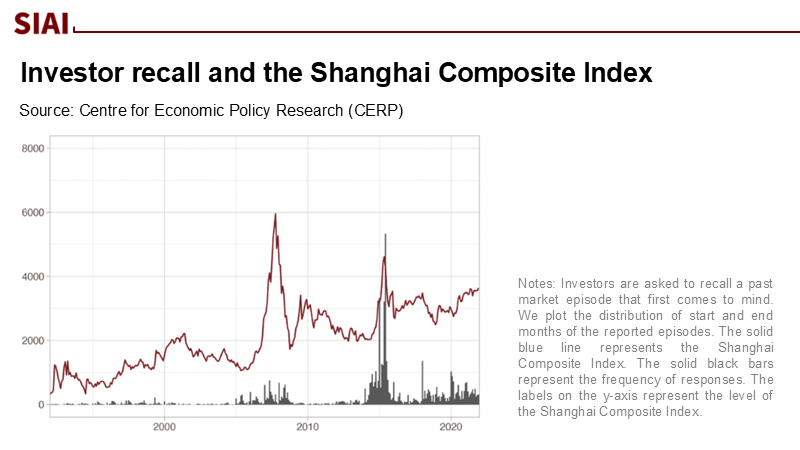

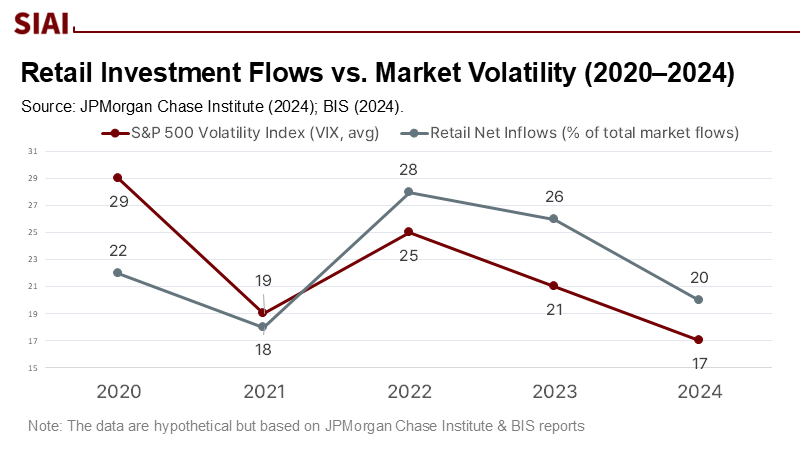

Recent research indicates that memory influences attention and trading intensity in ways that impact prices. A 2025 Review of Financial Studies article demonstrates how "memory-induced attention" distorts valuations around scheduled information events; when an outcome resembles a salient past, investors overweight it and underreact elsewhere. Complementary evidence from 2024 suggests that market memory triggers advance reactions and retail herding, priming preemptive buying when recent episodes are perceived as similar, regardless of fundamentals. At the household level, large-scale transaction data from 2008 to 2024 suggest that returns and volatility explain up to 40% of the swings in retail investment transfers, with the most pronounced chasing behavior among lower-income and younger investors. This is not a story of ignorance corrected by a pamphlet. It is a story of pattern-matching gone awry, with flow dynamics strong enough to amplify cycles. If many investors "buy the dip" because 2020's V-shaped recovery is top of mind, they can contribute to overheated rebounds; if they "sell the rumor" because 2008 is the only mental model, they can deepen drawdowns—each case lengthening the path back to equilibrium.

Overshooting Is the Macroeconomic Signature of Misremembered Crises

Overshooting is not merely poetic shorthand; it is a persistent macro pattern. Classic crisis playbooks document how panic dynamics push prices and quantities beyond what fundamentals justify, delaying stabilization. What's new is the tempo: the 2023 turmoil revealed that mobile, uninsured deposits, and social media coordination can convert small narrative sparks into outsized moves. Official post-mortems—from the Federal Reserve's 2023 SVB review to the FSB's 2024 assessments—concur that technology accelerates the speed of runs. Add to this: if the dominant analogy in investors' minds is 2008's slow-motion credit collapse, then a rates-driven duration shock can be misinterpreted as a solvency crisis, prompting procyclical deleveraging and precautionary hoarding that overshoots. Conversely, if memories fixate on 2020's rapid rebound, aggressive 'buy-the-dip' behavior can compress risk premia too quickly, fueling a snapback that outpaces earnings repair and invites a second correction. Both pathways are memory-consistent and recovery-distorting. The point is not that education is useless; it is that generic history education, unsupported by structural safeguards, may harden the wrong reflex. What's needed is a more nuanced approach to historical education, one that doesn't just teach the past, but also guides investors in applying historical patterns to today's regime.

A Better Toolkit: Structural "Memory Guards" Over Mass Memory Training

Suppose we accept that analogy-driven memory, not just information gaps, drives collective behavior. In that case, the policy emphasis should shift from the government 'teaching' investors the lessons of the last crisis to engineering the decision environment so that misapplied memories do less damage. First, liquidity regulation and stress testing should internalize the run dynamics of networked, uninsured funding by utilizing entity-level metrics, faster reporting, and communication protocols that assume real-time propagation rather than overnight processing. Second, portfolio plumbing can harden against retail herding: dynamic margining that leans against one-sided retail leverage in single-name equities; time-based order throttles for retail flows into thinly traded instruments during volatility spikes; and defaults that channel small savers toward diversified, low-turnover vehicles, leaving high-beta, complex strategies to genuinely qualified investors and institutions. Third, disclosures should undergo 'analogy audits': prospectuses, stress-test summaries, and supervisory communications that explain not merely risks, but which past episodes are valid comparators and which are not, using simple matrices that contrast 2008 (credit-led), 2020 (pandemic policy-shock), and 2023 (duration and network-run) regimes. The introduction of 'analogy audits' in disclosures can help investors make more informed decisions based on valid comparators, reducing the risk of misapplied memories causing damage.

Anticipating the Critiques—and Why They Fall Short

Critics will argue that this program is elitist, as it privileges institutions by nudging retail investors out of complex exposures. But the core of democratized finance is outcomes, not the freedom to be first in line to a stampede. The memory literature suggests that even sophisticated actors over-weight salient wins and under-weight losses; education alone cannot deprogram that tendency at scale, especially under stress. Moreover, evidence from 2023 shows that the structure of funding and customer networks—not just financial literacy—predicted run dynamics; in such an environment, how flows can move matters more than who moves them. Others will argue that reminding investors of objective history is itself stabilizing. Sometimes. Yet when the analogy is wrong, reminders entrench it: "last time policy cut rates—so this time, buy every dip," or "last time losses were credit—so this time, sell at any rumor of losses." A more honest approach is to make comparability explicit in official communications and product design, so that memory is guided toward the right precedent rather than blunted by generic exhortations to "remember the past."

Putting Qualified Capital in the Lead Without Closing the Door

The practical upshot is to sequence who sets the initial terms of recovery. In periods where collective financial knowledge is thin and narrative contagion is thick, design the system so valuation anchors come first from capital that can absorb noise and wait—pension funds, diversified insurers, large asset managers running benchmarked mandates—not from levered or concentrated retail flows primed by recent memories. This is not a ban; it is a throttle. As liquidity normalizes and prices reconnect to cash-flow data rather than analogies, constraints relax. Think of it as air traffic control for capital: staggered entry reduces the risk of collisions. The point is emphatically not to nationalize memory or to have the government dictate a single narrative. It is to ensure that when millions of individual memories pull against fundamentals, market microstructure and supervisory design dampen rather than magnify the error. Done well, recoveries are faster, drawdowns shallower, and the system less hostage to the last crisis investors happen to remember most vividly.

Stop Training for the Last Fire Drill

The bank runs of 2023 did not occur because individuals forgot about the events of 2008. They transpired, in part, because many people remembered 2008 too literally, failing to recognize how much technology had transformed the triggers and pace of the market. The outcome was a classic overreaction in a modern context—swift, interconnected, and performative. If we continue to address memory bias by imparting more lessons from past crises, we will be better prepared for the wrong type of emergency. A more effective approach is to align structures with reality: liquidity regulations that consider "real-time" crises; communication that clarifies the similarities between different episodes; and market frameworks that allow qualified, patient capital to establish initial indicators as sentiment shifts. This is not an argument against education; instead, it opposes miseducation. History still serves as an instructor. However, in finance, the educator must first determine which class we are attending. If we select the incorrect class, memory turns into a danger instead of a guide. If we choose the right one, recovery speeds up because we cease to repeat the past and instead focus on addressing the present.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements (BIS). (2024). Annual Economic Report 2024. Basel: BIS.

Caglio, C., Dlugosz, J., & Rezende, M. (2024). Flight to Safety in the Regional Bank Stress of 2023. AEA 2025 Program Paper (December 19, 2024).

Charles, C. (2025). Memory Moves Markets. Review of Financial Studies, 38(6), 1641–1684.

Federal Reserve Board. (2023). Review of the Federal Reserve's Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank (April 28, 2023). Washington, D.C.

Financial Stability Board (FSB). (2024a). Depositor Behaviour and Interest Rate and Liquidity Risks in the Financial System: Lessons from the March 2023 Banking Turmoil (Press release & report, October 23, 2024). Basel: FSB.

Financial Stability Board (FSB). (2024b). FSB 2024 Annual Report. Basel: FSB.

JPMorgan Chase Institute. (2024). Returns-chasing and Dip-buying among Retail Investors. October 1, 2024.

Kelly, S. (2025). Rushing to Judgment and the Banking Crisis of 2023. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Working Paper 2025-04.

Li, C., Sun, Q., & Wang, T. (2023). Retail investor attention and equity mispricing. Journal of Financial Markets, 68, 100811.

Sun, X., et al. (2024). Market memory, advance reaction, and retail investor herding. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 84, 102240.

U.S. Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). (2024). 2024 Annual Report. Washington, D.C.

U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (Michael J. Hsu, Acting Comptroller). (2024). Remarks quoted in GARP: "The Run on SVB: How Much Did Technology Have to Do With It?" March 15, 2024.

Comment