Aging into Abundance: Asia's New-Home Bias and the Coming Economics of Emptiness

Input

Modified

Aging turns housing scarcity into surplus New-build bias sidelines older homes and erodes value A 'refurbish-first' policy can turn empty properties into affordable assets

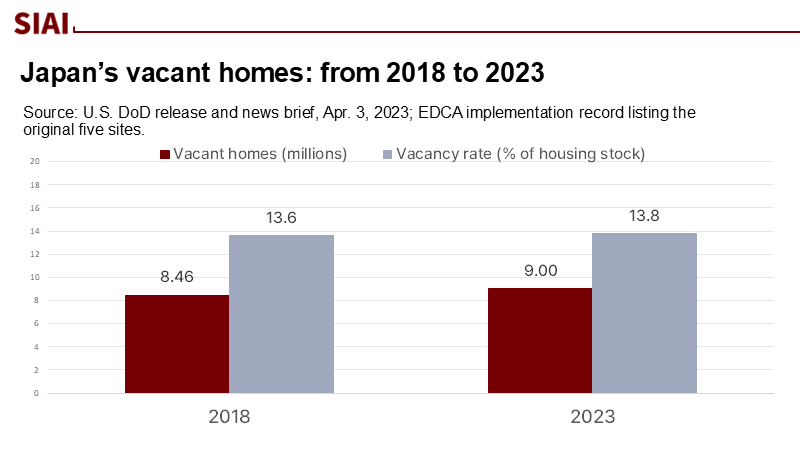

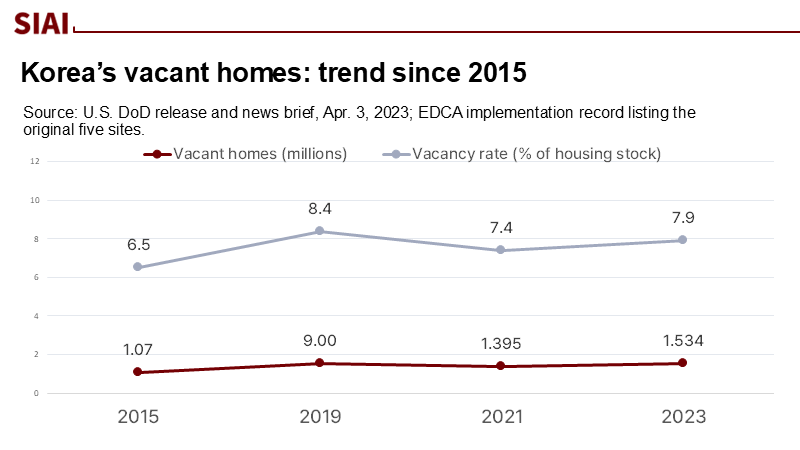

For the first time in living memory, the central problem of housing in parts of Asia is not scarcity but surplus. This shift is a result of complex cultural and market changes that are important for us to understand. Japan's 2023 Housing and Land Survey counted roughly 9.0 million vacant homes, equivalent to 13.8% of the stock—approximately one in seven dwellings remaining unused. That headline number is lower than some earlier doomsday forecasts, but it remains historically high and continues to rise as the population ages and household sizes shrink. South Korea is on a similar trajectory: by the end of 2023, approximately 1.53 million homes were unoccupied nationwide, representing a 44% increase since 2015. Read together, these figures signal a structural shift: in aging societies, housing is becoming abundant in the wrong places and at the wrong times. If the supply of older, unwanted homes continues to expand while buyers concentrate demand on ever newer buildings, the long-run price expectations that once anchored residential markets will weaken. That has profound implications not only for Asia but for Western Europe, where a cultural premium on longevity has long underpinned values. The policy challenge now is not simply to build more, but to re-value and reuse what we already have—before "abundance" curdles into blight.

Aging Societies, Accelerating Vacancies

The core of the problem is demographic arithmetic. Japan remains the world's leading example of rapid population aging, with policymakers and researchers often treating it as a harbinger state —a country that meets social and economic challenges before others, offering lessons—good and bad—for followers. The vacant-home rate, although not as catastrophic as some predicted a decade ago, remains at 13.8% and is concentrated in regions experiencing depopulation. Authorities have not stood still: since 2014, the Act on Special Measures Against Vacant Houses empowered local governments to intervene in dangerous properties, while a recent reform push tightened inheritance registration, enabled forfeiture of burdensome assets, and nudged owners toward sale or demolition—all designed to keep empty buildings from sliding into long-term limbo. These measures likely helped keep vacancy below dire projections, but they have not reversed the structural tide of aging and migration from rural to urban cores.

South Korea's pattern is younger but rhymes. By 2023, the country had recorded 1.534 million vacant dwellings, representing a 5.7% increase from the previous year and a 43.6% increase since 2015. The demographic backdrop is stark: the aging index has climbed rapidly (171.0 older adults per 100 children in 2023), and one-person households continue to rise—both trends that increase the number of housing "slots" relative to people. Vacant homes cluster in shrinking towns where jobs and services have thinned, intensifying a spatial mismatch between where empty units are and where households actually want to live. The policy conversation in Seoul has begun to echo Tokyo's—mapping inventories of vacant homes, considering targeted demolition, and exploring conversions—but the social preference that drives buyers toward new-build apartments remains powerful, which limits how much of the backlog can be absorbed without a cultural and regulatory reset.

Europe sits at a different cultural angle but faces converging pressures. Spain reported 3.8 million empty homes in the 2021 census—approximately 14% of the stock, rising to one-third in rural municipalities with fewer than 1,000 residents—an imbalance exacerbated by tourist demand in major cities. Italy combines one of the OECD's oldest housing stocks (with an average age of 47 years) with large pools of unoccupied dwellings in regions experiencing depopulation. Yet Europe also holds a strong norm that older buildings accrue value through durability, provenance, and craft—a norm reinforced by the EU's Renovation Wave and the 2024 Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), which together aim to upgrade 35 million buildings by 2030. The question is whether demographic headwinds will, over time, erode even Europe's longevity premium in the same way they have nudged Asia toward a bias for newness.

The New-Build Preference—and the Price of Disposability

The most crucial behavioral shift is not simply that some homes sit empty; it is that buyers discount older structures much more steeply than before. Nowhere is this clearer than in Japan's long-standing "scrap-and-build" culture. For decades, detached houses were understood to depreciate toward near-zero within 20–30 years, with land retaining most of the resale value; this made new construction the aspirational choice and "used houses" the market's residual. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle: the more people anticipate rapid depreciation, the more they prefer new builds, which further depresses the resale market for older stock and increases the likelihood that empty homes remain vacant. The losses are not abstract. A recent estimate indicated that nearby land values have plummeted by billions due to clusters of vacant houses, a localized negative externality that compounds across regions.

Korea is not Japan, but its apartment-centered urbanism increasingly channels a similar logic. In Seoul and other metropolitan areas, homeowners in aging complexes often rely on reconstruction, aligning politics and finance around the promise of a future "new" tower on the same site. Construction majors report receiving trillions of won in annual reconstruction orders, and the cultural history of the ap'at'ŭ danji explains how the very form has come to symbolize upward mobility and institutional trust. Even without a formal rule that structures lose value to zero, market attention gravitates to age, spec, seismic, and energy codes, as well as amenities—tilting relative prices toward new supply and away from over-30-year-old stock. This is not irrational; buyers are pricing real utility and risk. However, it penalizes longevity, and when overlaid on population decline outside core metros, leaves a growing ring of unloved, under-maintained buildings that face rising odds of demolition or abandonment.

If households believe that today's new build will be tomorrow's write-off, then "housing" increasingly behaves like durable consumption rather than long-lived capital. That reclassification matters. It changes mortgage horizons, shifts renovation calculus, and erodes the expectation that a home's structure will preserve value across generations. In aging Asia, the implicit discount rate on old buildings is rising; in parts of Europe, a different tradition still assigns positive option value to age because it can be upgraded into efficiency, comfort, and heritage tourism under the EPBD-driven standards. However, even there, patterns of rural depopulation and urban short-term rental concentration echo the Asian experience: an abundance of homes from which people are leaving, and a scarcity of homes where they are arriving. The practical implication for policy is to change the payoff profile of keeping buildings in service—so that, within a decade, a 30-year-old house is not considered almost worthless, but rather as a platform for affordable, low-carbon living.

From Liabilities to Livable Stock: A Refurbishment Playbook

Japan's recent policy experiments offer a template. The Vacant Houses Act shifted the legal balance away from an owner's unlimited right to neglect toward public interest in safety and land use; paired reforms created municipal "akiya banks," tightened inheritance registration, and introduced options to forfeit encumbered properties to the state. This mix of carrots, sticks, and information infrastructure attempts to break the cycle whereby heirs let houses decay because transfer is complicated, demolition is costly, or taxes perversely reward leaving the structure standing. The early result, according to recent analysis, is that vacancy rose more slowly than expected—evidence that rules and visibility can bend a market shaped by demographics. What remains is scaling these tools, especially cadastre modernization and safe demolition standards, to reduce the long tail of derelict assets that drag on neighbors' values and municipal budgets.

The economics of refurbishment are also turning. On the demand side, Europe's Renovation Wave and the 2024 EPBD recast commit member states to double annual renovation rates and target the worst-performing stock first—an industrial policy that treats energy upgrades and indoor-air improvements as public goods with private co-benefits. On the supply side, Japan's home-improvement market—measured at roughly ¥7.36 trillion in 2023 (approximately $52.6 billion USD)—is expanding in areas such as accessibility retrofits, seismic reinforcement, and efficiency upgrades. Europe still renovates far too slowly (~1% of the stock annually, versus around 3% needed by 2030). Still, the policy vector is transparent: reuse outperforms replacement when carbon budgets and municipal upkeep costs are priced correctly.

Education systems have a crucial role in shifting norms and capacity. Universities and vocational colleges can stand up retrofit studios that partner with municipalities to survey, triage, and redesign vacant stock—producing open-source design kits for deep energy retrofits, seismic and universal-design upgrades, and adaptive reuse into teacher housing, student residences, or elder-care co-ops. Teacher-training programs can pilot place-based residencies in refurbished homes in depopulating districts, linking social services, elder outreach, and school staffing into one anchor strategy. Administrators can leverage procurement to favor refurbish-first standards for campus expansions and pre-qualify contractors who meet EPBD-aligned performance criteria. Finally, policymakers can establish vacancy-to-value pipelines—such as registries, one-stop permitting, micro-grants, and financing guarantees—so that households have a predictable, faster path from derelict shell to a dignified dwelling. Transparent estimate: if Japan's vacancy rate rises a modest 0.2 percentage points every five years (the 2018–2023 increment), it would reach ~14.0% by 2030; if the 2025–2035 decade proves more intense as baby-boomers enter late old age, a 0.5-point rise per five years would push vacancy to ~14.8% by 2035. These brackets help determine the size of the workforce and the financing needed for conversion programs.

From Vacancy to Value

The statistic that now frames housing policy in parts of Asia is not "units built" but "units left behind": 13.8% of Japan's homes are vacant, 1.53 million in Korea are empty, Spain counts 3.8 million unused dwellings, and Italy's stock is old and heavily underutilized. As aging deepens and household sizes shrink, abundance arrives unevenly—oversupply of older homes in shrinking places alongside undersupply of new homes in growing ones. Left alone, a new-build bias will continue to siphon demand away from older structures, reinforcing the belief that a house's structural value evaporates within a generation. The strategic response is to change expectations and make reuse easy: embed Japan-style legal tools that prevent vacancy from metastasizing; scale Europe's renovation standards and finance; train a retrofit workforce; and turn universities and school systems into anchor customers for refurbished stock. If we do, "aging into abundance" can be a social dividend—lower housing costs, better energy performance, safer towns—rather than a slow-motion write-off of the built environment. The window is short, but the assets are already there. The task is to re-value them.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Asahi Shimbun. (2024, May 1). Survey: Almost 14% of all homes in Japan found to be vacant.

BPIE. (2024). EU roadmap for uptake of iBRoad2EPC schemes.

Business Insider. (2024, June 18). Japan's glut of abandoned homes … property market bleed billions.

European Commission. (2024). Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) — revised 2024.

European Commission. (2020–). Renovation Wave — renovate 35 million buildings by 2030.

Knight Frank. (2025, Jan. 22). Spain's proposed non-EU buyer restrictions explained (citing INE 2021 census).

Korea Herald. (2025, Mar. 5). Number of abandoned homes reaches 1.53 m in 2023.

Maeil Business (English). (2025, Jul. 30). Growth rate of houses in Seoul declines; apartments dominate.

Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (Japan). (2014–2024). Vacant Houses Act and follow-on measures (summarized in EAF).

Nippon.com. (2024, May 20). Number of Vacant Homes in Japan Reaches Record 9 Million.

OECD. (2025). Housing in Italy through the telescope …

Patience Realty (citing Yano Research Institute). (2024, Sep. 5). Japan 2023 home-renovation market growth.

Statistics Bureau of Japan. (2024). 2023 Housing and Land Survey (Basic Tabulation).

The Guardian. (2017, Nov. 16). Raze, rebuild, repeat: Japan's reusable housing revolution.

ULI Asia Pacific. (2024). Home Attainability Index.

Comment