When Industrial Subsidies in East Asia Hold Back the Best Firms

Input

Modified

Industrial subsidies in East Asia misallocate resources and dampen productivity Cheap credit and opaque, incumbent-favoring programs entrench weak firms Make support transparent, performance-based, and linked to skills and exit

The urgency of the issue is underscored by a stark number. In 2023, governments injected a staggering $108 billion into industrial subsidies for large manufacturers in East Asia. This figure represents a significant 1.3% of firm revenue in the OECD's global sample. The prevalence of below-market loans —the most cost-effective form of funding —nearly doubled since 2020, reaching a substantial $46.7 billion. These funds were heavily concentrated in a few sectors and countries, signaling an urgent need for reform.

Meanwhile, productivity growth in East Asia has relied more on firms maximizing their assets than on effective competition favoring stronger producers. This isn't just a minor accounting detail. It shows that industrial subsidies in East Asia are encouraging the wrong competitive priorities: favoring scale over efficiency and connections over innovation. The consequence is slower technology adoption, less progress towards leading firms, and a gradual decline in areas where the region once excelled.

Reframing the problem: industrial subsidies in East Asia and misallocation

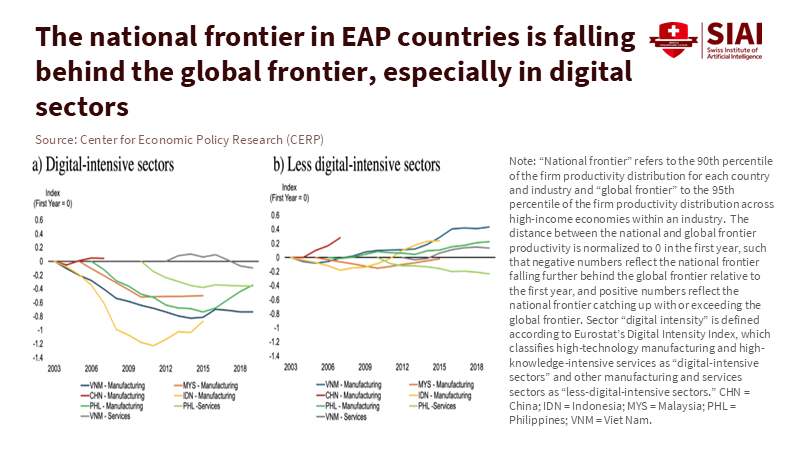

To understand why top firms are falling behind, we need to change our focus from "how much support" to "how support influences allocation." Throughout the region, the gap between national leaders and the world's best firms has grown, especially in digital manufacturing. Between 2005 and 2015, productivity at the global frontier of digital manufacturing surged by 76%, while the frontier in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Viet Nam increased by only about one-third during the same period. This gap didn't result from a lack of capital or talent. It stemmed from incentives that reduced the drive to shift market share and resources to the most efficient producers. When industrial subsidies in East Asia favor established companies, they reduce the cost of maintaining size rather than improving quality.

The micro evidence clearly shows the costs of misallocation. New research focuses on Southeast Asia and highlights significant potential gains from better allocation—over 80% for Indonesia and 20-30% for Malaysia and Viet Nam—even after correcting for measurement errors that may exaggerate the problem. These losses do not come from a single cause. They result from various factors, including subsidized credit, regulatory exemptions, and unclear procurement processes that direct resources to less efficient firms. In China, rigorous econometric analysis of industry-level policy changes shows that specific industrial policies increased revenue productivity variation within supported industries, a clear sign of misallocation. This shift shows how industrial subsidies in East Asia can change from a means of acceleration to a hindrance.

What the numbers show: industrial subsidies in East Asia and firm dynamics

The subsidy landscape is now significant enough to influence market structure. The OECD’s firm-level MAGIC database reveals that industrial subsidies are at their highest since the global financial crisis, averaging 1.3% of revenue in 2023 among covered firms, with sharp concentration in solar, semiconductors, aluminum, shipbuilding, and steel. Support is 4 to 8 times higher for firms in China than for their counterparts elsewhere. The fastest growth since 2020 has been in below-market loans, which tend to reduce market discipline. In summary, industrial subsidies in East Asia often protect balance sheets rather than promote productivity.

Zooming in reveals the imbalance more clearly. Among the world’s largest manufacturers, about half received subsidies in most observed years, with a median annual subsidy of around 0.6-0.7% of revenue. However, some outliers exceed 15%, mainly among Chinese companies and state enterprises. These outliers are significant for competition because even small, recurring advantages can distort tenders, discourage entry, and slow the spread of technology. The same OECD data links subsidies to sustained market-share increases for firms based in China, reinforcing the idea that allocation—not just total investment—has changed. Combined with the World Bank’s finding that East Asia’s productivity growth relies little on resource shifts between firms, a clear pattern emerges: industrial subsidies in East Asia stabilize existing players rather than support the ones we need.

Transparency is not just a point of discussion; it is a vital necessity. The WTO’s latest review stated that it could not obtain a “clear picture” of China’s industrial support across sectors such as EVs, semiconductors, steel, and shipbuilding, leading to a lack of accountability and effective program design. Independent studies indicate that more than 99% of listed Chinese firms reported receiving direct subsidies in 2022, often stacking multiple forms of support such as grants, tax breaks, and low-interest loans. In this context, even well-meaning programs risk becoming ineffective and dulling competitive pressure. The lesson from industrial subsidies in East Asia is not that support should stop; instead, it underscores the essential need for relatively transparent and comparable reporting to link funding to measurable outcomes.

The mechanism: how industrial subsidies in East Asia distort credit, competition, and skills

The main channel through which industrial subsidies in East Asia distort credit is by creating 'soft budget constraints'. When subsidized loans shield weak firms from the actual cost of risk, they create soft budget constraints. The IMF’s new cross-country database highlights the rise of “zombie” firms—businesses that cannot meet debt payments from profits yet continue operating due to cheap or directed credit. These zombie firms, often referred to as 'zombie companies', are typically characterized by their inability to cover debt service costs with current earnings and continue to operate due to the availability of cheap credit. They lower productivity in their sectors, crowd out investment from healthier competitors, and tie up valuable workers and equipment in low-return activities. This issue is a genuine concern in East Asia. The same OECD data shows a surge in below-market loans since 2020, especially where state-influenced banks implement industrial policies. If unaddressed, this situation can turn industrial subsidies in East Asia into a fixed burden on leading firms.

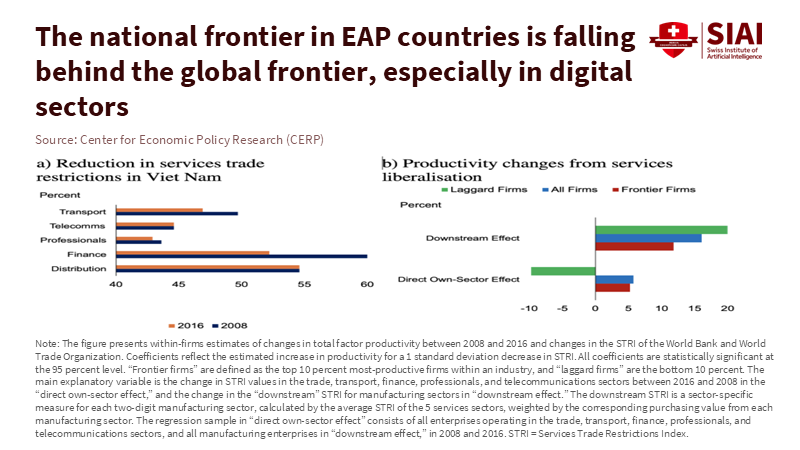

A second factor is favorable treatment for state-owned enterprises (SOEs). When SOEs have easier access to land, credit, or contracts, they can maintain size even when their productivity is low. Research focused on Vietnam finds that favored credit for SOEs significantly contributes to 'capital misallocation'. This term refers to the inefficient allocation of investment funds, often due to government policies or market distortions, resulting in lower productivity and economic growth. Broader regional diagnostics reveal a decline in investment efficiency despite substantial overall investment. The effect on private leading firms is apparent: they face fewer incentives to innovate, slower adoption of digital tools, and limited benefits from entering value chains. This is why the World Bank’s latest regional analysis highlights that East Asia's productivity challenge lies less in raising the average and more in allowing the best firms to advance, which requires competitive pressure and the freedom to grow. Subsidies that tie firms to outdated resource mixes hinder this goal. Industrial subsidies in East Asia must be modified to reward progress, not just size.

Finally, there is a twist regarding human capital. Support systems that favor incumbents also under-invest in management quality and skills. This happens because survival relies less on process improvement and more on meeting eligibility criteria. The result is slower technology adoption at the forefront and reduced spillover effects from foreign investors to local suppliers. The solution isn't more spending in the same format. It is reallocating public support away from general cost relief and toward building capabilities that enhance competition. By doing this, industrial subsidies in East Asia can increase returns to improving management, data systems, and worker skills, with the region’s strongest firms benefiting most.

Fixing the mix: making industrial subsidies in East Asia work like productivity policy

The aim isn't to eliminate support, but to change how it is used. First, ensure transparency is mandatory. Governments and significant recipients should publish a unified registry of all grants, tax breaks, concessional loans, and guarantees, including firm-level identifiers and expiration dates. The OECD calls for better disclosure; the region should push for more by linking disbursements to public dashboards. Transparency serves as a policy tool. It enables finance ministries to eliminate programs that cannot demonstrate impact. It provides regulators with a clear overview of where industrial subsidies in East Asia might distort markets.

Second, shift from direct aid to competitive practices. Replace open-ended financial assistance with time-limited, performance-based support. Transform below-market loans into income-contingent innovation credits that decrease as firms achieve their operational targets—such as exporting at market prices, achieving energy-efficiency goals, or moving up the value chain. Projects should be assessed with independent scoring that prioritizes productivity-related factors: total factor productivity growth, quality-adjusted output per worker, and the spread of digital tools. This aligns industrial subsidies in East Asia with actions that create positive spillovers and reduce the risk of zombies by tying funding to goals rather than survival.

Third, improve resource allocation through strict rules, not random solutions. Strengthen bankruptcy and exit processes so chronically unprofitable firms cannot rely on subsidized credit. Prevent recipients from using aid to acquire struggling competitors unless the buyer can prove operational upgrades. In regions where SOEs have a significant presence, ensure fair competition: borrowing costs should reflect actual expenses, procurement must be transparent, and support should have strict end dates. If state banks provide policy lending, apply independent risk models, and publish details of the implicit interest rate differences, the OECD notes, then place a cap on these rates. This approach would bring industrial subsidies in East Asia back to a level that promotes rather than hinders private investment.

Fourth, link public funding to building capabilities. The World Bank's regional analysis indicates that productivity rises when firms blend competition with skills and digital resources. Allocate a fixed portion of any industry program for management training, data adoption, and supplier development with quantifiable learning goals. For educators and administrators, this is a vital connection. Universities and technical institutes can co-create micro-credentials in operations, data analysis, and quality management that are recognized in subsidy assessments. Ministries can include procurement training—understanding how to bid, comply, and report—into adult education programs for SMEs. Boards can require management quality audits before receiving support. When industrial subsidies in East Asia prioritize skills alongside capacity, the benefits grow.

There is also a practical path for schools and systems. Focus on industry-related capstone projects in factory analytics, lean production, and energy optimization; connect them to local supplier improvement initiatives to enhance learning through real projects. Create regional centers of excellence where faculty, students, and companies can test new process technologies on shared lines. For policy schools, instruct on program evaluation and cost-effectiveness using data from the subsidy registry, and publish yearly “allocation reports” that assess whether public support is directing resources toward more productive firms. These steps may seem technical, but they are crucial to ensuring that industrial subsidies in East Asia support the region’s best producers rather than merely shielding the average ones.

We started with one number: $108 billion in industrial subsidies and a rise in below-market loans. These figures do not indicate whether public support should cease; they remind us that how we design support—and the data we gather about it—determines whether funding drives change or stagnation. Currently, the structure of industrial subsidies in East Asia is too focused on productivity. It stabilizes established firms, limits reallocation, and slows progress. The solution is attainable. Prioritize transparency—link support to measurable gains that enhance total factor productivity and digital tool adoption. Strengthen exit criteria to create space for new, improved firms. And direct a meaningful portion of every program toward developing management and worker skills. By taking these steps, the following significant figure we highlight will not be the total of subsidies, but the extent of the productivity gains they help achieve.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Chen, G. (2022). Policy and misallocation: Evidence from Chinese firm-level industrial policies. European Economic Review, 149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2022.104195.

International Monetary Fund. (2023). The Rise of the Walking Dead: Zombie Firms Around the World (WP/23/125). Washington, DC: IMF.

International Monetary Fund. (2025). Regional Economic Outlook: Asia and Pacific, October 2025—Chapter on Investment Efficiency and Capital Allocation. Washington, DC: IMF.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2025a). How governments back the largest manufacturing firms: Insights from the OECD MAGIC database (OECD Trade Policy Paper No. 289). Paris: OECD Publishing.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2025b). The state of play of industrial subsidies as of 2023. Paris: OECD Publishing.

World Bank. (2020). de Nicola, F., Nguyen, H., & Loayza, N. Productivity Loss and Misallocation of Resources in Southeast Asia (Policy Research Working Paper 9483). Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. (2025). Firm Foundations of Growth: Productivity and Technology in East Asia and Pacific (overview and book materials). Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Trade Organization (as covered by Reuters). (2024, July 17). China’s industrial support programmes lack transparency, WTO says.