Who Pays the Tariff Is Changing, and U.S. Households Are Next

Input

Modified

Importers paid first; households pay next Diversified supply chains raise prices and cut choice Use narrow, time-bound tariffs with pro-trade fixes to limit welfare loss

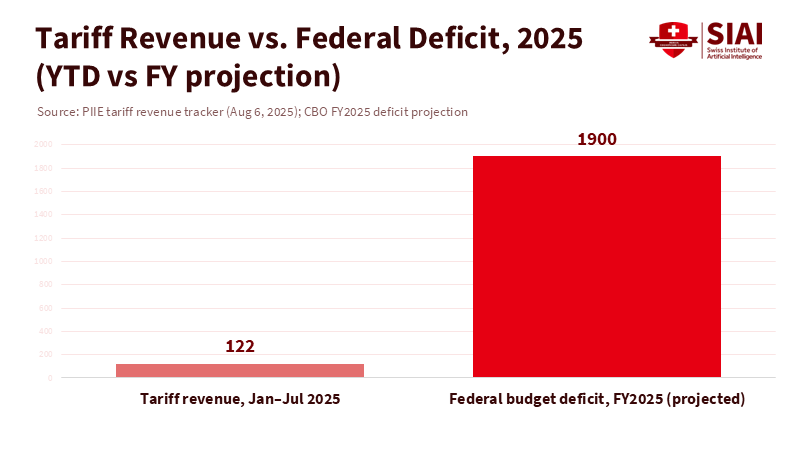

There is one statistic that should guide discussions about who pays the tariff. As of July 2025, the U.S. government had collected around $122 billion in tariff revenue. This amount covers only about 6.5% of the projected federal deficit. While this small fiscal impact might not grab headlines, it suggests who really pays the tariffs. U.S. firms and consumers are facing costs at the border and in stores. Early evidence this year shows many importers have absorbed the initial costs, tightening their margins to keep prices from rising sharply. However, as foreign producers move away from a volatile U.S. market and as sourcing shifts to more expensive suppliers, the burden is likely to fall increasingly on consumers. This means U.S. households will see higher prices, fewer choices, and a growing risk of persistent inflation that can impact budgets even before official statistics reflect it.

Who pays the tariff today, and why that's changing

The early data for 2025 do not suggest that foreign exporters are absorbing most of the tariff. Through July, analysts tracking customs payments report that U.S. businesses have shouldered most of the tariff costs, lowering their markups to keep customers. This mirrors findings from the 2018–2019 trade war, where tariffs mainly affected domestic importers and consumers instead of foreign sellers. In other words, while the importer gets the bill, the economic cost is shared between the firm and the household, with limited contribution from the foreign producer unless they cut prices to maintain their market share in the U.S. The immediate effect in 2025 has been to soften, not eliminate, price increases—especially for items where retailers face intense competition and cannot afford price jumps mid-season. This is just a temporary calm before a larger wave of changes. As inventories deplete and contracts renew, importers will try to build back their margins. The key question is not whether price increases will happen, but when they will occur.

We can already observe the shift in supply chains that will place costs on households. U.S. ocean imports from China dropped by 28.3% year-over-year in June 2025, reducing China's share of U.S. containerized imports to 28.8% from nearly 40% in mid-2024. Buyers have turned to Southeast Asia—Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand—to keep goods available. This diversification has a cost. Fragmented supply chains lead to smaller production runs, more complex logistics, and less negotiating power with any single supplier. The outcome is higher costs that ultimately show up in retail prices. This aligns with longer-term trends: when tariffs rise, buyers often switch suppliers rather than pressing foreign prices downward, and those switching costs are reflected in consumer prices. This transformation turns a border tax into a tax on households.

Who pays the tariff when supply chains shift

Tariffs not only increase prices; they also reshape networks. This reshaping is evident in both official and research data. A Federal Reserve Bank report comparing 2024 to May 2025 highlights significant declines in import shares from high-tariff countries, including China, along with increases from Vietnam and the European Union. A recent study on trade rerouting finds that Vietnam's surge in exports to the U.S. includes a notable share of goods with Chinese inputs and ownership. Nearshoring to Mexico has similarly contributed to this shift. In 2023, Mexico surpassed China as the top U.S. supplier of goods and has maintained that status, capturing some of the market China lost. Each of these changes results in increased costs, including longer transport routes for components, duplicated compliance and testing, and the need to onboard new suppliers, all of which reduce economies of scale. Over time, these costs will be reflected in retail prices. This transition signals a change in who pays the tariff from mostly businesses to increasingly households.

Policy dynamics amplify the pressure. In 2025, tariff rates on some Chinese goods were dramatically increased, reaching triple digits for targeted categories, compounding earlier Section 301 actions. The immediate effect was not a straightforward price spike; instead, it created chaos. Importers hurried to place orders to avoid deadlines. Then they scaled back, which added to the monthly volatility in wholesale and producer prices. Prices for steel mill products rose even as overall producer inflation briefly eased this spring. As the year progressed, broader price measures stabilized at modest year-over-year rates. Still, the details painted a concerning picture: goods disinflation became fragile, while supply chain costs simmered beneath the surface. Collectively, these factors indicate a near-term shift in who bears the cost as contracts renew in 2026. Price levels do not need to surge for overall well-being to decline; fewer models and lower quality for the same price also represent hidden taxes.

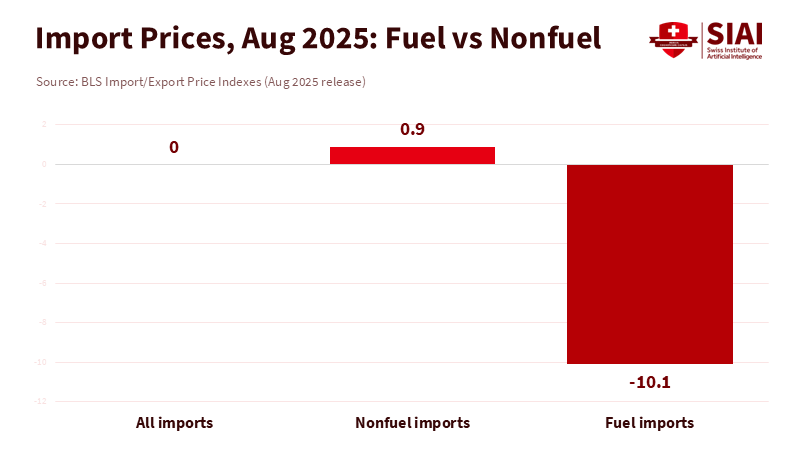

Who pays the tariff in the inflation fight

In August 2025, inflation was at 2.9% year-over-year for the headline CPI and 3.1% for core inflation. While these figures are manageable, they rest on unstable ground. Import prices for energy fell over the year, masking the rising costs of non-energy goods affected by new tariffs. The import price index shows double-digit declines in fuel on a 12-month basis through August, buffering retail gasoline and freight costs. That support is unlikely to last indefinitely. As tariff-driven changes in sourcing become established, retailers will face a straightforward decision: continue compressing margins or raise prices. With wages remaining rigid and financing costs still significant, price increases are becoming more probable. The longer the diversification persists, the more likely it is that households will pay the tariff through higher prices or "shrinkflation," where smaller package sizes disguise real price hikes.

There is also a time element that typical inflation reports overlook. Evidence from early 2019 showed that the full burden of tariffs fell on U.S. importers and consumers, reducing real income by about $1.4 billion each month. Follow-up research found little absorption by foreign producers and more source switching. This mechanism is essential now: if foreign producers will not absorb the tax, and importers can only endure it for a limited time, the eventual transfer of costs to households depends on the timeline. The more the U.S. relies on tariffs as a regular tool, the more supply chains will permanently adapt away from the U.S. market. This solidifies higher prices for goods. Even if headline inflation stays around 3%, a reshaped mix of imports can weaken goods disinflation compared to prior expansions, complicating rate-setting and wage negotiations. This slow-building cost of trade policy does not show up in a single month of CPI but affects grocery bills for years.

Who pays the tariff in the long run: welfare, choice, and growth

The impact on welfare extends beyond just prices. Households lose out when their choices narrow, quality declines, and innovation slows. Tariffs, especially those that vary across categories, create unpredictability in product planning. Firms may delay product launches or reduce options. For example, a smartphone that offered four storage choices may only have two. A furniture line that could have had eight colors might only ship with five. None of this shows up as a rapid price increase, but it still reduces consumer welfare. Research from the last trade war indicated significant shifts in trade without notable price savings for consumers; these costs were passed on to U.S. households through higher effective prices and less variety. The evidence from 2025 suggests we are witnessing a similar trend with a broader range of suppliers. If this pattern continues into 2026, U.S. households will feel the impact through reduced options just as much as through higher prices. That still counts as paying the tariff.

Growth is at risk for another reason: tariffs act like a tax on intermediate inputs. When prices for components increase or when firms must change to new suppliers, productivity suffers. A one percentage-point increase in per-unit costs across a wide range of inputs can determine whether a new product line gets approved or shelved. We saw hints of this issue in mid-2025: producer prices decreased in March for some volatile categories, but materials like steel products rose due to new tariffs, while households' inflation expectations increased. These mixed signals are characteristic of stagflation risks: economic growth slows under the pressure of rising production costs while price relief remains incomplete. A tariff program intended to be temporary but repeatedly extended can embed this risk. Over time, the cost of protection is not only borne by consumers today; it also affects workers who miss out on future productivity gains.

The bill always comes due

We started with a straightforward number—$122 billion in tariff revenue through July 2025—which seems substantial until compared to the deficit and the scale of U.S. consumption. This underscores that the financial benefit of tariffs is limited, while the costs for the private sector accumulate. Initially, the burden appears to fall on U.S. businesses. However, supply chains are not static. As producers withdraw from the U.S. market and buyers shift to more expensive, complex networks, the responsibility for paying the tariff is moving to households. Prices increase slightly. Choices decrease. Quality diminishes at the margins. This does not trigger a headline CPI crisis, yet overall welfare declines just the same. The real question is not whether we can shift the cost to someone else, but whether we are willing to subtly and gradually tax our own consumers.

What should our response be? If tariffs are to be used, they should be narrow, precise, temporary, and linked to specific goals, along with a trusted exit strategy for the markets. Regulators should pair them with faster customs processing, mutual recognition of standards with allies, and support for logistics improvements that lower the non-tariff costs of diversification. Educators and workforce leaders should prepare for a future where jobs related to tradable goods will require more knowledge in supply chains and vendor management than ever before. If we ignore these necessary actions, then in 2026, the answer to who pays the tariff will be the same as it is becoming in late 2025: American households, one receipt at a time.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Amiti, M., Redding, S. J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2019). The Impact of the 2018 Tariffs on Prices and Welfare. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 187–210.

Amiti, M., Redding, S. J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2020). Who's Paying for the U.S. Tariffs? A Longer-Term Perspective. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 110, 541–546.

Associated Press. (2024). Mexico overtakes China as the leading source of U.S. goods imports.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025a). Consumer Price Index Summary—August 2025.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025b). U.S. Import and Export Price Indexes—August 2025.

Census Bureau. (2025). Trade in Goods with China (monthly detail).

China Briefing. (2025). U.S.–China Tariff Rates—What Are They Now?

East Asia Forum. (2025). Who's eating Trump's tariffs?

Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. (2025). Why Predicted and Actual Tariff Rates Diverged in May 2025 (Economic Brief).

Iyoha, E. (2025). Exports in Disguise? Trade Rerouting During the U.S.–China Trade War (Working Paper). Harvard Business School.

Peterson Institute for International Economics. (2025a). Who is paying for Trump's tariffs? So far, it's U.S. businesses (Realtime Economics Blog, September 16).

Peterson Institute for International Economics. (2025b). Trump's tariff revenue tracker: How much is the U.S. collecting? (August 6).

Reuters. (2025a). U.S. ocean imports from China tumbled 28% in June on tariff hikes.

Reuters. (2025b). U.S. producer inflation muted before import tariffs blast (April 11).

tralac. (2025). Who actually pays the tariff? It's complicated! (August 19).

Wall Street Journal. (2025). The U.S. and China are still in a trade war. Here's how much business they do (April).