No Deal, New Playbook: Why the EU-China Trade Deal Stalled and What Comes Next

Input

Modified

The EU can afford to wait, but China cannot German auto troubles have hardened Europe’s stance Europe now builds leverage through new trade routes and partners

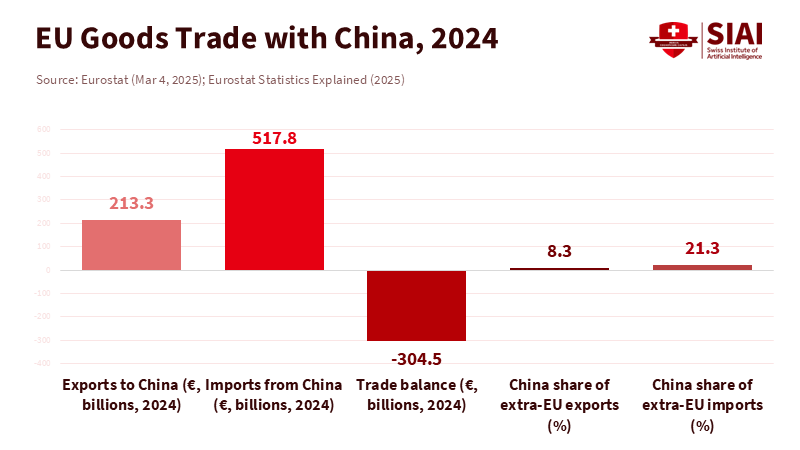

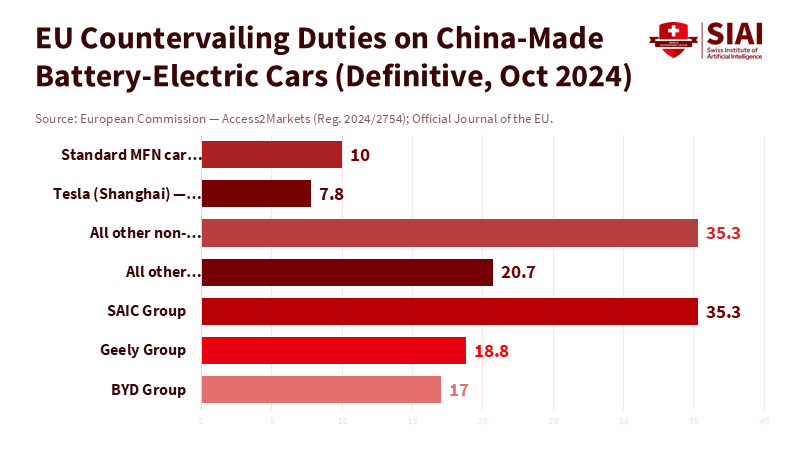

In 2024, the European Union ran a €304.5 billion goods deficit with China. Only 8.3% of exports from the EU went to China. This imbalance shaped the negotiations this year. Europe could wait; Beijing could not. Two more facts are essential. First, Brussels imposed five-year countervailing duties on Chinese battery-electric cars: 17.0% for BYD, 18.8% for Geely, and up to 35.3% for SAIC, in addition to a standard EU car tariff of 10%. Second, Washington established a 10% global baseline tariff in April 2025, with higher reciprocal rates on several countries later that summer. In this context, July’s EU-China summit in Beijing produced some symbolism but no breakthroughs. The stalled EU-China trade deal is not a failure in negotiation; it reflects a shift in leverage. Europe’s options outside a negotiated agreement have improved, while China faces mounting pressures at home and abroad. In this new situation, “no deal yet” is a strategy, not a sign of passivity.

The EU-China trade deal that never was

The EU-China trade deal that never materialized, despite the significant efforts and discussions, stands as a testament to the complexity and challenges of the negotiations. The Jul 24, 2025, summit, which marked 50 years of diplomatic relations, lasted just one day and ended without promises to open markets. Leaders exchanged predictable remarks: the EU called for “rebalancing” after its record deficit, while China requested “proper handling of frictions.” The negotiating landscape changed significantly, with Reuters reporting a tense atmosphere, while official EU statements remained neutral, and Chinese comments emphasized practicality. Talks about replacing tariffs with a price-undertaking system—minimum prices and volume commitments by exporters—were raised in the spring and discussed through the summer. However, they never matured into a political agreement. This is significant. Price undertakings are complex and challenging to monitor across many models and brands. They also invite immediate comparisons from other partners, especially the United States. Beijing found that a low-cost reset—some rhetoric along with limited incentives—would not convince Brussels in 2025.

Economic issues amplified the political landscape. Eurostat data showed that the EU’s deficit with China remained around €300 billion in 2024, while the share of EU exports to China stayed small. This left European leaders less vulnerable to the costs of delay than many expected. At the same time, global tariffs from Washington—implemented in April and adjusted in July—dampened the benefits of any quick EU-China tariff agreement: even if Brussels reached a side deal, exporters still faced US barriers that influenced their investment plans. Beijing’s main request at the summit was explicit: lift or replace EV duties. Brussels’ core message was equally clear: rebalancing with enforceable safeguards. Those goals were incompatible that day. There will be more discussions; the reasoning that led to no deal will still be relevant when they meet again.

Germany’s auto shock and the bloc’s narrow room

It might seem that Berlin would always try to find a middle ground. This time, that was not the case. Germany opposed additional EV duties in 2024 and sought a political solution in 2025. However, the EU still imposed final countervailing duties, and the market shifted anyway. BYD has now entered the EU’s monthly sales rankings and has sometimes outsold Tesla. Chinese brands roughly doubled their share in the EU this year, while Europe’s traditional carmakers struggled. Domestically, Germany’s auto suppliers face weak demand and tight margins. Internationally, Volkswagen’s sales in China fell in 2024 and continued to decline into 2025, even though its BEV share increased in Europe. The German industry still employs about 750,000 people. Still, its influence over EU trade defense is limited when the rest of the bloc views the situation as one of structural subsidies and overcapacity. Berlin can slow down discussions, but it cannot veto the inevitable changes.

The outcome is a tight space for compromise. Price undertakings or hybrid quota-price systems may protect specific German models produced in China or safeguard joint-venture interests. However, they cannot appear as hidden subsidies that compromise the EU’s legal arguments. Nor can they undermine the credibility of broader risk-reduction measures now inherent in EU policy, from anti-subsidy investigations in several sectors to digital enforcement against rapidly expanding platforms. Here, the politics of the single market are crucial: any concession framed as a one-time favor for cars invites similar demands in solar, wind, medical devices, and more. Industrial policy and trade defense have merged. This makes a headline “deal” harder to announce and easier to implement through small, incremental steps.

For education leaders, this situation is not abstract. Automotive and battery supply chains are being rebuilt within Europe. New programs in mechatronics, power electronics, industrial software, and materials science represent the future of labor policy. German and Central European universities can respond quickly by offering 6–12-month stackable modules that retrain combustion-engine specialists in electric powertrains, battery management systems, and thermal management. They can also form applied research consortia with Mittelstand suppliers focused on low-cost LFP chemistries, and create joint testbeds with EU original equipment manufacturers for vehicle-to-grid protocols. If the EU-China trade deal is delayed, skills policy becomes essential to keep plants and communities surviving long enough to benefit from the next wave of investment.

From China-first to periphery-first: Europe’s alternative lanes

One lesson from 2025 is that a “China-first” path doesn’t open up the entire landscape. Brussels is now pursuing a periphery-first strategy. The Middle Corridor—Trans-Caspian routes connecting EU markets to Central Asia and western China without relying on Russia—is moving from idea to reality. This year, the EU set aside €3 billion for this corridor under the Global Gateway initiative, in addition to the €10 billion pledged in 2024. The EU's unwavering commitment to this initiative reassures stakeholders about its proactive approach. The EU also hosted a summit in Luxembourg with Central Asian, Caucasus, and Black Sea partners to coordinate permits, ports, and rail connections. These initiatives may not dominate news headlines, but they serve as fundamental safeguards. Even limited success shifts bargaining power: more reliable east-west transit that avoids Russia and reduces single-route dependence increases Europe’s patience with the stalemate in negotiations with Beijing.

Southeast Asia is another area of focus. The EU already has modern free trade agreements with Singapore and Vietnam. In 2024-2025, it resumed or sped up negotiations with the Philippines and Thailand and has indicated a path toward agreements with Malaysia. Trade commissioner Maroš Šefčovič has described these as key steps toward deeper EU-ASEAN relationships. None of this replaces China, but it strengthens Europe’s position. As access to other markets progresses, the cost of delaying an EU-China trade deal decreases. This reality was evident in the choreography of the July summit as much as in any official statements.

For universities and vocational systems, the periphery-first approach means that mobility and research connections should align with this policy. Consider dual-degree programs with engineering schools in Thailand and the Philippines focused on port logistics, grid integration, and customs technology; faculty exchanges on battery recycling with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan; EU-funded micro-credentials in customs digitization for corridor authorities; and internships for European students in ASEAN supply chain companies that will support EU plants. This should be combined with targeted instruction in languages and trade law. The talent trained today will operate the infrastructure that will provide leverage in the future.

What a workable bargain would require

If a deal is to be reached in 2026, three elements will be necessary. First, there must be verifiable safeguards. A credible price-undertaking model for electric vehicles would require transparent minimum prices and clear product definitions, along with rigorous monitoring to prevent circumvention and model variations. European analysts have pointed out that the Commission is cautious about enforceability, and for good reason. Without precise commitments, there will be leakage. Second, there needs to be reciprocal agreements across sectors. Beijing will want relief on electric vehicles; Brussels will seek progress on access to public procurement, data governance, and export controls affecting European products. The issue of rare-earth, where China’s export rules have strained EU supply chains, will also be on the table. Third, the EU must protect itself from US pressures. Any concession from the EU to China that appears overly generous will be evaluated against Washington’s tariff stance. Both China and Europe are aware of this, which raises the standard for a “big” deal until the US tariff environment stabilizes.

There is a narrow path forward. It involves step-by-step agreements that Europe can defend as consistent with WTO rules and that China can view as a way to maintain dignity. One possible sequence could involve trading a limited, time-bound price-undertaking for electric vehicles in exchange for concrete steps from the EU regarding procurement and data localization, along with a corridor package in Central Asia that Beijing could accept. Another option is to pair tariff freezes with expedited EU access to ASEAN markets that help diversify rather than entirely separate supply chains. Most importantly, the sequence should be structured to endure US disruptions—global baseline tariffs, reciprocal adjustments, or Section 301 revisions. If those tensions escalate, “no deal yet” continues to seem reasonable. If they diminish, a technical resolution could be promoted as a significant agreement.

For education policymakers, the focus should be on investing in flexibility. Fund programs that offer adaptable skills across various supply routes—maritime logistics and rail operations in the Middle Corridor, compliance and product testing for ASEAN components, and after-sales services, diagnostics, and grid management for electric vehicles within the EU. Create small, modular programs that can be shifted as regulations change. Keep the industry engaged through cooperative placements that can turn into jobs as new plants launch. Do not wait for the EU-China trade deal to clarify the outcome. Train the workforce that makes any outcome feasible.

One statistic should guide our thinking: in 2024, the EU exported just 8.3% of its extra-EU goods to China while importing more than double that share from China, resulting in a €304.5 billion deficit. These figures explain why an EU-China trade deal did not materialize this summer and why it might not happen soon. Europe can accept a holding pattern while it strengthens trade defenses, redirects infrastructure through Central Asia, and expands partnerships in Asia beyond China. China can also delay, but at increasing costs: EV duties are fixed, US tariffs have reset the global standards, and European politics now reward apparent “risk reduction.” The innovative approach is not to pursue a superficial agreement but to build leverage—skills, routes, and enforceable rules—so that when a deal is reached, it is solid. For educators and administrators, this means taking immediate action on programs that support the transition Europe has already chosen. For policymakers, it means using the absence of a deal as a strategy, not a source of anxiety. The next summit should validate this approach or improve it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Al Jazeera. (2025, Jul 24). China’s Xi calls for pragmatism at summit with EU in uncertain times.

Bloomberg. (2025, Jul 31). Chinese EVs recover in Europe to pre-tariff market share level.

Council of the European Union. (2025, Jul 24). 25th EU–China summit—EU press release.

European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA). (2025, Sept 24). Economic and market report: Global and EU auto industry—H1 2025.

European Commission (Access2Markets). (2024, Dec 12). EU Commission imposes countervailing duties on imports of BEVs from China (Reg. 2024/2754).

European Council on Foreign Relations. (2024, Oct 9). Divided we stand: The EU votes on Chinese EV tariffs.

Eurostat. (2025, Mar 4). Slight decline in imports and exports from China in 2024 (EU–China deficit €304.5bn; China share of EU exports 8.3%).

Eurostat. (2024/2025). China–EU international trade in goods statistics (8.3% share of extra-EU exports).

GMF (German Marshall Fund). (2025, Jul 22). Diplomacy in an age of disruption: The EU–China summit.

JATO. (2025, Jun 24). Chinese automakers double European market share in May (5.9%).

MERICS. (2025, Feb 20). China bets on a low-cost reset with Europe + EU–China trade tensions.

Pekingnology. (2025, Oct 19). Explainer: EU’s technical difficulties with EV price undertakings.

Politico. (2025, Jul 31). Trump issues order imposing new global tariff rates effective Aug 7.

Reuters. (2024, Oct 3). Germany to vote against EU tariffs on Chinese EVs, sources say.

Reuters. (2025, Jun 27). Exclusive: Beijing ties cognac deal to EV tariff talks with Europe.

Reuters. (2025, Sept 25). BYD outsells Tesla in EU for second month.

Reuters. (2025, Jul 24). China’s Xi calls for proper handling of frictions at tense summit with EU officials.

RFE/RL. (2025, Oct 20). EU readies new trade routes—and a challenge to Beijing and Moscow—at Luxembourg summit (Global Gateway; €3bn + €10bn for Middle Corridor).

U.S. White House. (2025, Apr 2). Fact sheet: President Donald J. Trump declares national emergency; imposes 10% baseline global tariff.

White & Case. (2025, Apr 4). President Trump orders 10% global tariff and higher reciprocal tariffs.

Volkswagen Group. (2025, Oct 10). Global deliveries update; BEV gains in Europe; China decline.

VDA—German Association of the Automotive Industry. (2025, Oct 5). Survey: investment activity constrained; weak EU demand.

VDA—German Association of the Automotive Industry. (2024). Workforce developments (≈773k employed).

Washington Post. (2025, Jul 24). Rebalancing relationship with China ‘essential,’ EU president says.