Two Storm Tracks: China's Disinflationary Trade Shock and America's Financial Shock

Input

Modified

China drives disinflation through trade, while U.S. markets export financial shocks Japan and Korea feel both pressures Clear separation of channels guides better policy

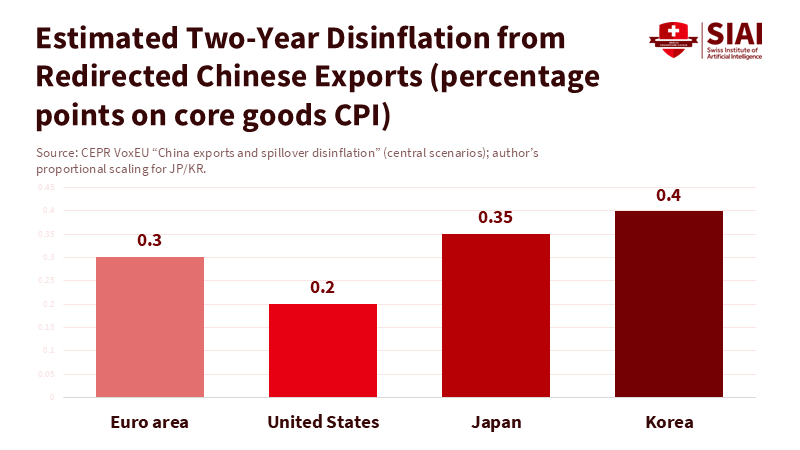

In 2025, model-based scenarios suggest that redirected Chinese exports could lower euro-area core inflation by approximately 0.3 percentage points over two years. A separate analysis estimates that the near-term disinflationary effect for major economies will be approximately 20 basis points, even in the absence of any policy changes. These forecasts are not extreme; instead, they represent likely outcomes based on recent trade patterns. For Japan and Korea, whose exports closely align with those of China, the impact on the business cycle is more significant than for many other countries. At the same time, U.S. financial conditions tighten in waves that quickly affect Asian equity, credit, and exchange-rate markets. This creates a dual impact: a Chinese trade-price trend that puts pressure on the domestic industry, and a U.S. financial conditions trend that alters the cost of capital—addressing these issues as a single matter results in ineffective responses. Recognizing both storm tracks highlights the importance of clear communication, which is essential for understanding and implementing targeted measures that can enhance resilience.

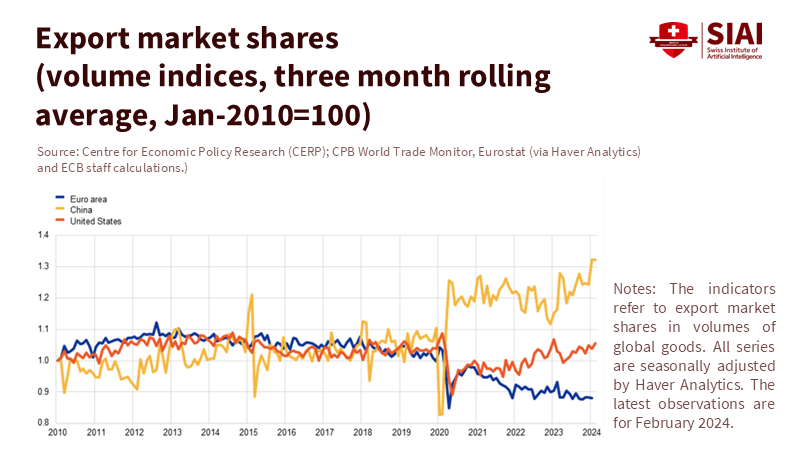

How China exports disinflation—and rivalry

China's export activities create a disinflationary price trend in global goods markets. When tensions between the U.S. and China lead to a shift in shipments to other markets, core inflation in the euro area can decrease by about 0.3 percentage points over two years. This decrease has a significant impact on the technology and housing sectors. A separate analysis predicts that by 2025, the effect on both the U.S. and the euro area could be nearly 20 basis points if monetary policy remains unchanged. The primary driver of this change is on the supply side, as an increase in goods at lower prices occurs. The broader impact stems from demand-side pressures, which lead to lower profit margins and delayed investments in competing sectors. This change in the business cycle is especially noticeable in Japan and Korea, as they directly compete with China in the machinery, electronics, and transport equipment industries.. It is influencing order books, utilization rates, and wage-setting practices in these countries.

The trade overlap is evident in bilateral flows. In mid-2025, China's exports to Japan and Japan's exports to China remained in the tens of billions of dollars each month, despite fluctuations due to changes in currency and tariffs. These are not minor connections; they are essential parts of the industrial framework. When Chinese goods are redirected to markets where Japanese and Korean firms operate, they encounter prices set by the global marginal supplier, which refers to the supplier with the lowest cost of production and therefore sets the market price. The domestic effect resembles a competitiveness shock, characterized by weaker pricing power, thinner margins, and delayed investment plans. This stems from the business cycle, not a financial shock.

Japan's recent data highlight this pressure. Manufacturing PMIs fell below 50 in mid-2025 due to declining export orders, and official reports noted weakness in steel and autos. Meanwhile, GDP growth in 2024 was nearly flat, indicating how swings in international demand can overshadow domestic growth. Korea experienced a similar trend: downgraded growth forecasts for 2025 at around 1% and a contrast between strong housing prices in Seoul and weaker conditions elsewhere. Monetary policy cannot shield vulnerable sectors from tariffs; it can only provide temporary relief. Fundamental changes must come from industrial adjustments, such as diversifying export markets, and education policies that facilitate reallocation, including retraining programs for workers in declining sectors.

When the United States sneezes: financial spillovers to Japan and Korea

The other storm track involves global risk prices. U.S. financial conditions—a combination of rates, credit spreads, equity valuations, and the dollar—tightened sharply from late February 2025, reflecting lower growth expectations and uncertainty around tariffs. This tightening quickly affects Asia through capital flows and asset prices. Studies on return spillovers reveal that the U.S. market strongly influences equity returns in the Asia-Pacific region. For Japan and Korea, which have open economies and active equity and foreign exchange markets, the effects are swift: higher risk premiums, weaker currencies, and more expensive external financing. This represents a financial-cycle spillover, distinct from the trade-price spillover from China.

Frequency-domain neutral-rate estimates provide additional insight: the financial factor's influence on policy-rate changes is most prominent in the U.S. and significant for China. At the same time, Japan and Korea's sensitivities vary by frequency—the business cycle, which refers to the fluctuations in economic activity over time, in Japan, and the financial cycle in Korea. The 'neutral rate' refers to the interest rate that neither stimulates nor restricts economic growth, and its stabilization is crucial for managing the financial cycle. This means that a U.S.' risk-price' shock impacts both the business and economic cycles abroad, but not in the same way. For East Asia, this has clear implications: when conditions on Wall Street fluctuate, the neutral rate that stabilizes the financial cycle can shift even if local economic factors remain unchanged. Therefore, mimicking the Fed's actions is not always necessary or sufficient; the key is understanding how U.S. conditions impact local economies.

This is where education and industrial policy become essential. Financial spillovers change the investment hurdles that firms, universities, and research institutions face. A sudden increase in credit spreads can halt collaborative R&D and apprenticeship programs when sectors need to adjust. If ministries and university boards view these initiatives as optional, they will be the first to face cuts. A more innovative approach treats these as stabilizers in challenging times: continue funding skill pipelines during periods of widening spreads and declining export orders. This helps workers transition into areas where domestic value can still grow—such as power electronics, precision machinery, and green components. The benefit is not just social; it serves as a safeguard for competitiveness.

Policy alignment for two spillovers

Separating the two shocks clarifies which tools to use. The disinflation from China requires targeted education and industrial policies, such as standards, procurement, and export finance, that help local firms advance in the value chain. In contrast, the U.S. financial spillover necessitates emergency credit lines and liquidity support to prevent viable firms from failing to meet interest coverage during temporary market stress. Both scenarios require macroprudential measures to avoid excessive borrowing from exacerbating volatility, even as rates adjust in response to local conditions. One shock affects margins while the other changes discount rates. Confusing the two can lead to the wrong responses at least half the time.

What does "alignment" look like in practice? First, create a simple spillover map that distinguishes between trade-price effects and risk-price effects, pairing each with corresponding policy responses. Next, establish automatic stabilizers in education budgets: if export orders in vulnerable sectors drop by a specified percentage, apprenticeship opportunities and mid-career upskilling vouchers should automatically increase for a determined period, funded by a stabilization account. Third, establish "conversion tracks" in technical universities to allow displaced workers to earn micro-credentials within a year by recognizing prior learning. Fourth, ensure public R&D financiers maintain funding levels even when financial conditions tighten, even if project-level discount rates rise, to avoid starving the pipeline precisely when private capital withdraws. These are not extraordinary programs; they are cost-effective insurance. For example, if a 0.3-point drop in sectoral inflation correlates with a 1–2% revenue decline, a 12-month 20% increase in affected programs typically covers half the investment gap.

Lastly, coordinate macro policies considering the two-storm perspective. Suppose China's business-cycle impact is dominant and domestic inflation is decreasing. In that case, rate cuts can boost demand—paired with tighter macroprudential measures in overheated property markets to prevent financial-cycle slippage. If the U.S. financial shock is more significant, prioritize liquidity support, FX swap lines, and targeted credit guarantees while ensuring policy rates align with domestic inflation trends. Throughout this process, communicate clearly about which shock is most pressing and which tools are being implemented. Markets prefer clarity over confusion.

Japan and Korea are facing two external pressures that move in different directions and at different speeds. China spreads disinflation through goods markets; the United States spreads volatility through financial markets. One pulls prices down in sectors where these economies compete directly; the other raises discount rates and tightens financing conditions, even when local economic fundamentals remain stable. The mistake is treating both as a single "global shock" that can be addressed with one tool. The solution is to differentiate the channels, match instruments to their effects, and secure education and retraining budgets as stabilizers for tradable industries. This way, when the subsequent 0.3-point price decrease occurs, or the next tightening of U.S. financial conditions sends ripples across the Pacific, schools won't suspend new student cohorts, firms won't cancel apprenticeships, and labs won't halt projects. Two storm tracks, one coherent strategy, and reduced wasted time.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2025). R in East Asia: business, financial cycles, and spillovers.* BIS Working Paper No. 1285.

Dieppe, A., Frankovic, I., & Liu, M. (2024). "China exports and spillover disinflation: Three scenarios." VoxEU/CEPR.

ECB (2025). "US financial conditions and their link to economic activity." Economic Bulletin, Box article.

Hollywood with Chinese Characteristics - Modern Diplomacy.

OEC (2025). "China and Japan trade profile," and "Japan and China trade profile." Observatory of Economic Complexity.

Reuters (2025). "Japan's factory activity shrinks on falling export orders, PMI shows," and "Japan Jan–March crude steel output forecast to fall 2.4% y/y—METI."

SECO (2025). Economic Report 2025: Japan. Embassy of Switzerland in Japan.

Tran, M. P. B., et al. (2023). "Market return spillover from the US to the Asia-Pacific." Pacific-Basin Finance Journal (open-access version).

VoxEU/CEPR (2025). "The Great Wall of Chinese goods: The effect of tariff-induced re-routing on euro-area consumer prices." VoxEU Column.