Priced for Perfection: What AI-Era Tech Must Prove to Earn Today's Valuations

Input

Modified

U.S. tech stocks are priced for perfection AI capex and energy needs strain growth assumptions Education policy must enforce cash-first discipline

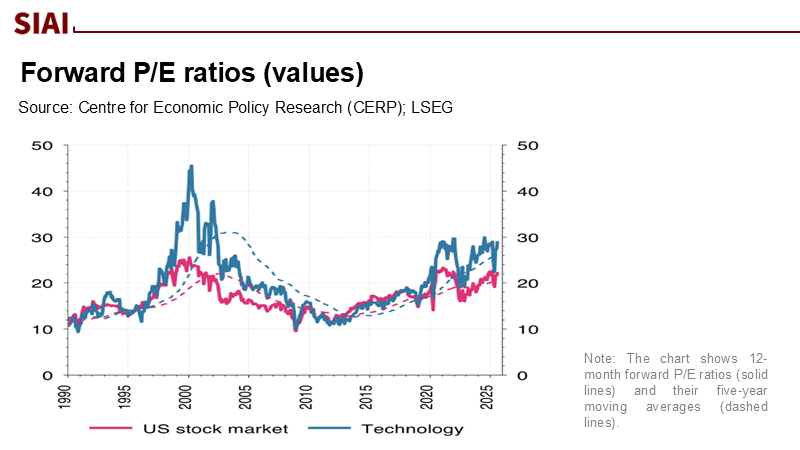

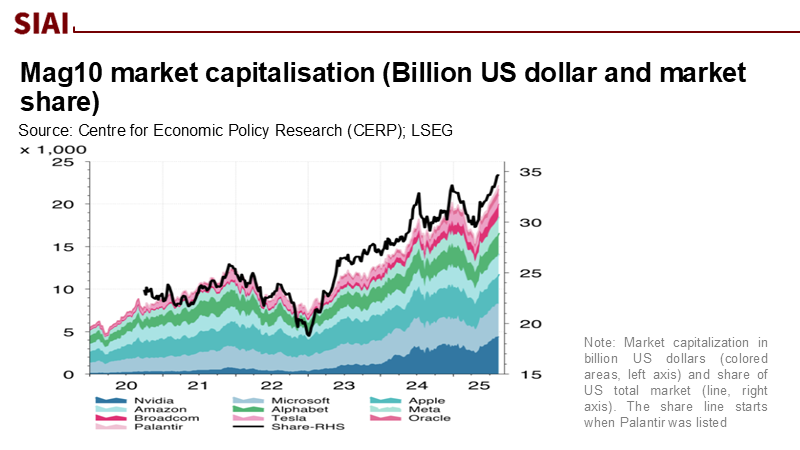

One number frames the entire debate: seven stocks now make up roughly 34% of the S&P 500's market value. When so much capital rides on so few firms, and when those firms are central to an AI story whose costs and cash flows are still shaping up, we are no longer just discussing preferences. We are valuing a single narrative as if it were a fact on a balance sheet. By early September 2025, the S&P 500 traded near a forward P/E of about 22. The Nasdaq-100's forward P/E hovered around 27. That suggests an earnings yield close to or below the 4.1% yield on the 10-year Treasury, which offers little reward unless profits grow quickly and sustainably. Meanwhile, individual AI-exposed stocks carry sky-high multiples: Arm above 200 times trailing earnings and Palantir in the high hundreds—ratios that can shift from promising to stressful when growth slows. This may not be pure bubble territory everywhere, but it certainly points to prices set for perfection, and perfection is a demanding business model.

The ratios say more than we admit

The argument for 'overvaluation' does not rely solely on one measure; instead, the familiar metrics already raise concerns. Index-level forward P/Es remain well above 5- and 10-year averages, even after brief pullbacks. Within tech, many leaders still trade at growth-based premiums that anticipate several years of solid performance. Take Nvidia—the most apparent winner from the AI development trend. It posted 56% year-over-year revenue growth last quarter and still trades around 49 times trailing earnings, while Arm and Palantir are valued two to ten times higher. This disparity reveals two points. First, the market is not naive; it does adjust for substantial fundamentals. Second, beyond the few companies that have achieved operational momentum and actual cash flow, we are paying for potential. The math behind that potential is harsh: if growth falters, duration risk kicks in. However, the growth potential also presents an opportunity for investors to see significant returns, a prospect that should instill optimism and hope.

Part of the issue is conceptual. The PEG ratio, which divides P/E by expected earnings growth, often gets touted as a safety signal when it hovers around 1. However, two pitfalls lie beneath this assumption. The growth used in PEGs is almost always a prediction, and predictions often align with narratives. Additionally, PEGs embed a risky assumption: that earnings growth comes with little extra capital and stable margins. In an AI cycle with immense capital requirements and increasing depreciation, that is a significant leap. A PEG below one based on unrealistic growth is not a bargain; it's a gamble on uncertainty. Note: In this piece, when discussing PEG, we use the traditional formula (P/E ÷ growth). When citing index valuation levels, we refer to forward P/E from FactSet (S&P 500) and MacroMicro (Nasdaq-100) as of early September 2025.

Concentration increases the stakes. As of August, the 'Magnificent Seven' accounted for around 34% of the S&P 500's market cap, an unusual weight for passive investors in pension funds and college endowments. When such concentration meets high multiples, portfolio math stops being diversified; it becomes reliant on a few cash-flow stories. Even industry leaders see the over-exuberance. Sam Altman—who knows the upside—has warned that investors are 'overexcited' and that we may be in a bubble, even while AI spending is climbing. The point is not that AI is insignificant. It's that valuation represents a claim on future cash, not a judgment on technological potential. Diversification is crucial for mitigating risks and maintaining a secure investment portfolio, a strategy that should provide investors with a sense of security and protection.

Cash flow, capex, and the power bill

Valuations represent promises about cash flow, so let's follow the money. The AI expansion has shifted from small-scale tests to industrial-scale infrastructure. Big Tech's AI-related capital expenditures for 2025 are expected to reach the mid-hundreds of billions, with some estimates around $364 billion. Bulls claim this spending is the new foundation of the economy. Yet the same analyses that promote this figure also show emerging signs of fatigue: several analysts now predict a slowdown in capex growth beginning in 2026 as depreciation takes a toll and unit economics face challenges outside the early adopter phase. If the capex wave crests, suppliers downstream—from chips to power systems—must justify their premiums by meeting actual workloads, not just reservations. This is not a sign of doom; it is a normalization of an investment cycle. However, it matters for valuation because the EV/EBITDA metrics often used as cash flow proxies can easily inflate in years of rising spending and then compress harshly when the focus shifts to free cash after capital expenditures (capex).

Energy is the second constraint that strengthens the 'overvaluation' argument. The IEA predicts data-center electricity demand will double to about 945 TWh by 2030, with AI as the main driver. The EIA now expects U.S. electricity sales to grow faster in 2025-2026, specifically noting data centers as a contributing factor. These are realities of the power grid, permitting, and tariffs, not just slides in a presentation. Even if the industry enhances supply with more efficient chips and better scheduling, the timing gap between energy infrastructure and compute procurement can stretch deployment cycles and delay revenue recognition in ways P/E ratios often overlook. Investors can afford to pay up for growth; however, utilities —the companies responsible for providing the necessary energy —cannot create substations based on optimism. For firms valued as if demand is immediate and flexible, delays in energy availability are not just abstract risks—they are real, near-term cash-flow obstacles.

We've already seen how quickly narratives get repriced when cash and capacity clash. Figma launched on July 31 at $33, soared above $100 within days, and then, after its first post-IPO guidance indicated slower growth, fell to the mid-50s to high-60s. No scandal, no fraud—just the harsh math of expectations and time. This example does not highlight a single company; it illustrates a broader trend. In a market where forward multiples assume success on ambitious AI-related plans, earnings seasons become evaluations of whether future cash is arriving as expected. This highlights the importance of exercising caution and adopting prudent evaluation strategies in the face of uncertain growth and high valuations. This necessity should prompt investors to exercise care and caution.

What educators and policymakers should do now

If this seems like just a Wall Street concern, think again. Public universities and school systems are purchasing AI licenses, redesigning curricula, and committing to multi-year vendor contracts with pricing often built on the same ideal curves the market expects. The first policy step is woefully practical: treat AI procurement as an investment through a discounted cash-flow lens. Demand time-bound ROI targets—for instance, saved grading time per course, verified improvements in completion or placement rates, or measured reductions in the backlog of student services—and tie contract renewals to actual results, not vendor promises. This approach is not anti-innovation; it mirrors the discipline that valuation demands from investors. The opportunity cost is significant. When the 10-year U.S. Treasury yields around 4.1%, any spending on ed-tech must meet a high standard to outperform cash equivalents or core infrastructure. In simple terms: if a tool cannot show results that exceed the risk-adjusted alternative, it is not worth the cost.

Second, manage concentration risk in ways index investors cannot. When seven firms represent a third of the benchmark, endowments and public pension funds—often the same entities that support campus capital plans—are effectively tied to one sector's valuation cycle. Boards should stress-test their funding models against a scenario where AI capex growth slows sharply in 2026, tech earnings fall short, and multiples revert to long-term averages. The revenue line on your campus—licensing rebates, gift flows linked to appreciated stock, even extra income from tech conferences—will feel the impact. The strategy here is clear: diversify the sources of cash supporting your digital strategy so a tech correction doesn't lead to teaching cuts.

Third, build capacity for evaluation within departments. The most troubling data point from this summer is not about chips; it is about outcomes. A widely shared analysis linked to MIT suggests that roughly 95% of generative AI trials yield no measurable return for companies. There is debate surrounding methodology and definitions, but the trend is consistent across evaluations: the failure often lies in implementation—specifically, workflows, governance, and incentives—not in model capabilities. For higher education, the lesson is to focus on process redesign and faculty training before rushing into tool adoption. Bring researchers and registrars together. Support method audits that define success metrics in advance. And share negative results. Trials that never reach completion waste time; those that publish their failures help everyone bypass mistakes.

Finally, teach the basics of valuation to those making technology choices today. A dean does not need complex math, but everyone managing public funds should understand the difference between trailing and forward P/E, the hidden assumptions in a PEG, and why EBITDA serves as only a loose proxy for cash when capital expenditure is high. These concepts are not mere financial details. They provide a way to connect a vendor's pitch to next year's budget item. Suppose our institutions can explain to students why a bond yielding 4% is not free money. In that case, we can also teach ourselves why a 27x multiple on promised earnings deserves serious scrutiny about timing, power, and personnel.

The temptation with every technology trend is to make valuation a question of belief. A better approach is less captivating but more robust. Let's start with the concentration that defines today's market, the multiples that represent our collective hopes, and the cash flow that must appear to support both. The S&P 500's forward P/E is near 22, the Nasdaq-100's is near 27, the 10-year yield is around 4%, and the 34% weight of seven stocks together paints a picture of a market that has banked a lot of future expectations. Combine that with the likelihood of AI capital expenditures peaking in 2025-2026 and the real-world constraints of electricity, and the potential for disappointment is clear, even as the technology continues to transform our lives. None of this argues against AI or the companies developing it. It advocates for a cash-focused perspective in classrooms, procurement offices, and policy discussions: specify outcomes, assess risk, understand potential downsides, and renew only what delivers results. If we do this—calmly and consistently—today's "priced for perfection" can become tomorrow's paid-for reality. Anything less may mean our education budgets ultimately support someone else's narrative.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Apple. (2025, Jan 30). Apple reports first quarter results.

Barron's. (2025, Sep 9). An AI spending slowdown would drag down the market: Goldman Sachs. Barron's

Business Insider. (2025, Aug). Tech guru Erik Gordon says investors will 'suffer' far more from the AI boom than the dot-com crash.

FactSet. (2025, Aug 1). S&P 500 earnings season update: forward 12-month P/E.

Figma. (2025, Jul 30). Figma announces pricing of initial public offering.

Fortune. (2025, Aug 19). Wall Street isn't worried about an AI bubble. Sam Altman is.

FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. (2025, Sep). 10-Year Treasury Constant Maturity (DGS10).

IEA. (2025, Apr 10). AI is set to drive surging electricity demand from data centres.

Investopedia. (n.d.). PEG ratio: What it is and how to use it.

Investors Business Daily. (2025, Sep). Figma stock plunges after first earnings report post-IPO.

MacroMicro. (2025, Aug). U.S.—Magnificent Seven share of S&P 500 market cap.

MacroMicro. (2025, Sep). U.S.—Nasdaq-100 Index forward P/E.

NVIDIA. (2025, Aug). Q2 FY2026 results: revenue up 56% YoY.

Reuters. (2025, Jul 31). Figma shares surge 158% in blowout market debut; IPO priced at $33.

U.S. EIA. (2025, Aug 5). U.S. electricity demand to grow faster in 2025–26; data centres cited.

Yahoo Finance. (2025, Aug 1). Big Tech's AI investments set to spike to $364 billion in 2025.

Comment