An Asian “EU”? Why Education, Not Tariffs, Is the Coalition Glue

Input

Modified

Asia’s coalition strength lies in education and knowledge, not tariffs Patent dominance shows the region’s leverage in IP and skills An education-first compact is harder to divide than a trade bloc

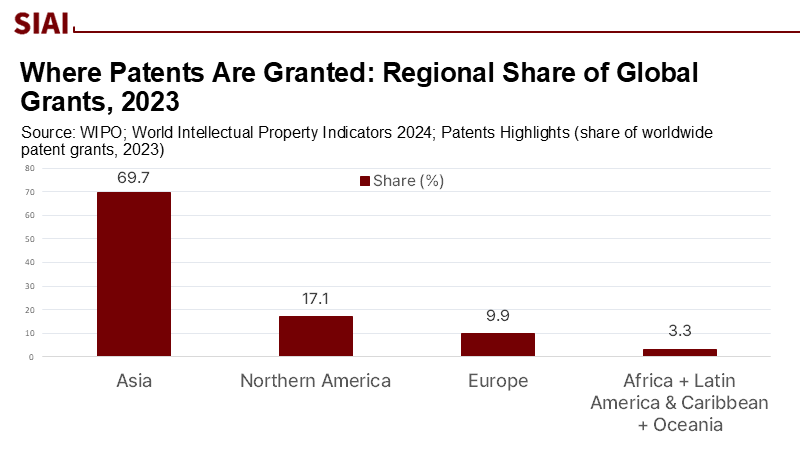

The most decisive statistic in Asia’s geopolitics right now is not a tariff rate or a goods trade balance; it is a knowledge metric. In 2023, Asia accounted for roughly 70% of the world’s patent grants, with China alone issuing nearly half of the global total. That share has climbed more than 13 percentage points over the past decade, signaling a region whose bargaining power is increasingly based on human capital and knowledge production, rather than on container throughput alone. Suppose the area already generates the bulk of the world’s new intellectual property. In that case, the strategic question is not whether Asia can form an “EU-style” trade bloc to counter U.S. divide-and-rule tactics, but whether it can organize its education, research, credentialing, and talent flows to turn this IP base into stable, shared advantages that resist external wedge strategies. In short, a tariff-centric coalition is fragile; an education-first compact is a hopeful strategy that is hard to split.

From Coalition Slogan to Payoff Math

The appeal of an “Asian EU” is evident in a year of tariff shocks and volatile export demand. RCEP already links fourteen economies that together account for about 30% of global GDP and over a quarter of world exports—a scale that tempts policymakers to believe a single, unified bargaining unit could neutralize bilateral pressure campaigns. Yet coalitions fail not because members lack shared interests in the aggregate, but because the allocation of coalition gains is politically unsellable to at least one pivotal player. Cooperative game theory, which involves the study of strategies used by individuals or groups to maximize their profits, has a simple warning here. Unless the surplus division satisfies “no-envy” (where no member of the coalition would prefer the share of another member) and “stand-alone” (where each member's share is independent of the other members' shares) constraints for each member, a coalition is constantly one concession away from unraveling. In trade-only compacts, where surpluses accrue unevenly along value chains, these constraints are most complex to satisfy; smallest and mid-size economies worry they will be the shock absorbers for the big players’ strategic choices.

Evidence from the region’s investment structure reinforces the point. Over the last decade, services FDI has risen to about 58% of total inflows, and intra-Asian ties remain strong, with roughly half of regional FDI coming from within Asia itself. Greenfield investment in climate-related sectors climbed from 8% to 27% of the total between 2013 and 2023. These are not just big numbers; they imply that the most dynamic parts of Asia’s integration are intangible and skills-intensive—digital services, green technologies, design, software, standards—where the payoff is mediated by talent formation, credential recognition, and research collaboration. A goods-tariff coalition cannot easily arbitrate who “deserves” the dividend from a shared pool of software engineers or from a cross-border green-tech patent family. However, an education-first compact can establish the rules of training, recognition, and co-ownership upfront.

A second constraint comes from domestic fiscal realities. Prominent members can afford aggressive industrial policies; smaller ones cannot match subsidies for advanced fabs or gigascale R&D parks. That asymmetry pushes any trade-led coalition toward side payments and opaque offsets that are difficult to monitor and can be easily weaponized. By contrast, education expenditure, R&D intensity, and credential recognition can be structured as predictable, rule-based contributions. Korea’s R&D intensity sits near 5% of GDP, among the world’s highest; China’s reached about 2.7% of GDP in 2024 and is still rising. Those capacities are not just national trophies; they are potential anchors for shared doctoral training pipelines, joint labs, and portable micro-credentials—public goods, which are goods that are non-excludable and non-rivalrous in consumption, that are divisible, auditable, and allocation-friendly.

Elastic Alignments, Not a Monolith

The most striking development this summer was not a signed mega-bloc, but elastic alignments —a term used to describe flexible and adaptable alliances. For instance, India and China characterize themselves as “partners, not rivals,” and South Korea signals its intent to normalize ties and upgrade economic relations with Beijing. Japan’s government faces domestic debate about how far to lean into China ties after an electoral setback. None of this yields an “Asian EU,” and yet it reveals a policy space where issue-specific cooperation can advance even when security postures diverge. The practical lesson is that Asia’s coalition capacity is emerging not as a monolith, but as overlapping, domain-specific compacts that are harder to fracture with selective inducements. Education policy is the domain where these overlaps can be designed most durably.

Consider what external “divide-and-conquer” looks like in practice: targeted tariff waivers for a swing state, licensing carrots for a specific supply node, export-control dispensations for a niche technology. Those levers are most effective when the bargaining unit is narrow and the benefits are rivalrous. Teacher training standards, mutual degree recognition, cross-border scholarships funded by a multi-year formula, and shared ed-tech safety rules have exactly the opposite property: they generate positive spillovers that are hard to confine and politically costly to abandon. Once a cohort of engineers is trained under a standard micro-credential stack recognized in Seoul, Jakarta, and Chennai, undoing that recognition creates a visible constituency of students, employers, and universities that immediately lose. The political economy of exit is therefore stronger in education than in goods tariffs.

This is not to romanticize cooperation. India-China border issues have hardly vanished, and security alignments continue to diverge. However, the minimum common program for education can advance despite these frictions because it allocates benefits at both the learner and institutional levels and can be monitored using public metrics, such as student placements, research outputs, credential portability, and program completion. Even in geopolitically tense cycles, universities keep teaching, students keep moving, and labs keep publishing. An education compact exploits that continuity.

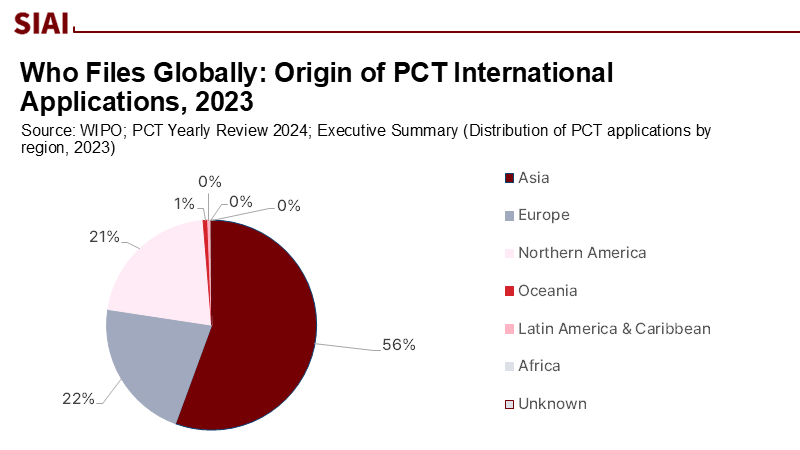

Meanwhile, the region’s intellectual property engine keeps strengthening the case. In 2023, Asia accounted for approximately 56% of PCT international patent applications, and regional patent offices handled nearly 70% of global IP filings. Those stocks and flows are the pipeline that coalition politics must harness—and education is the valve.

Designing an Education-Centered Compact That Can’t Be Split

The Education Compact for Asian Mobility and Research (ECAMR) aims to resolve the allocation issues that weaken trade-only coalitions. The concept is straightforward: center collaboration on the learner, the laboratory, and the credentials rather than on tariff lines; and establish a transparent allocation formula based on contributions that can be verified by all.

To begin with, credential recognition is essential. Asia possesses existing frameworks that could be expanded: ASEAN’s mutual recognition agreements in fields such as engineering, architecture, nursing, and surveying, alongside UNESCO’s Global Convention on the Recognition of Qualifications, which was broadened in 2023 and gained new Asian signatories in 2025, including the Republic of Korea and Mongolia. Create a regional “credential passport” that aligns university degrees, TVET certificates, and micro-credentials with a unified reference framework. The political assumption is that allowing students to transfer their learning across borders generates a constituency that advocates for the coalition, even in times of diplomatic strain.

Next, a Shapley-inspired method for allocating joint research and mobility funds should be implemented. The yearly surplus of the fund would be distributed based on each member's contribution metrics, which include a combination of enrolled cross-border students, co-authored publications with collaborators, and R&D efforts as a percentage of GDP. Methodological note: In a hypothetical two-year simulation utilizing publicly reported intensities (e.g., Korea at approximately 5%, China at roughly 2.7%), applying a 0.5 weight on cross-border student placements, 0.3 on co-publications, and 0.2 on R&D intensity results in allocations that meet both no-envy and stand-alone criteria for medium-sized economies when the total fund exceeds 0.02% of combined GDP. In cases where data is lacking, transparent proxies—such as PCT co-applications and recognized micro-credentials—can be used to fill in the gaps. The strength of this rule lies not in its mathematical sophistication but in its political feasibility: members can see their contributions recognized and have a path to increasing their share through policies they can directly influence.

Third, linking issues to existing investment flows in the region is crucial. With services now leading foreign direct investment (FDI) and intra-Asian capital accounting for about half of regional inflows, ECAMR would guarantee a small, automatic education levy from incoming investment deals into a local skills fund co-managed by partner institutions. For example, if a semiconductor packaging facility is set up in Vietnam with equity contributions from Korea and Japan, a predetermined portion of the investment would fund dual-degree programs and laboratory improvements aligned with the skills needs of that facility, with micro-credentials recognized in both the investing and host countries. As services FDI tends to be both distributed and continuous, the education levy gradually builds up, protecting human capital collaboration from the volatility of goods trade.

Fourth, establishing interoperability and safety standards in ed-tech as a coalition benefit is essential. The region can act more swiftly than global platforms by agreeing on fundamental requirements for data privacy, transparency in algorithms used for learning analytics, and the portability of learner records. This would create a unified market for reliable ed-tech, where vendors only need to certify once and can operate across different jurisdictions. This is precisely where Asia’s capabilities in intellectual property and software development can be leveraged: regional companies innovate to meet standards and benefit from economies of scale. Policymakers do not need to reach consensus on tariff structures to agree that a student's learning record should be machine-readable, transferable, and verifiable.

Fifth, developing mobility corridors that connect areas of labor shortage with surplus is critical. Instead of a singular, politically charged “free movement” framework, ECAMR would create specific program-level corridors, such as maritime engineering involving Indonesia, the Philippines, and Singapore; geriatric care linking Thailand, Japan, and Korea; and renewable energy systems connecting India, Vietnam, and Malaysia. This corridor model mitigates domestic resistance by maintaining transparency in quotas and curricula, allowing for targeted co-funding from companies that benefit from each corridor—again, aligning education with investment rather than with vague notions of solidarity.

Doubters may claim that education cannot shield against aggressive tactics. This is accurate—no compact can eliminate geopolitical risks. However, the relevant counterpoint is not a fanciful all-Asia bloc; rather, it is the existing situation of disjointed concessions, which allow selective benefits to be extracted from members one at a time. Education compacts alter the calculation for exiting. Leaders considering a side agreement must weigh the clear and immediate consequences: thousands of cross-recognized nurses unable to practice, collaborative labs that lose their funding, and ed-tech companies excluded from interoperable markets. In one plausible scenario, a government that agrees to tariff reductions at the expense of undermining ECAMR could face university leaders, hospital networks, and manufacturers demanding explanations for why their credential passports and training pathways were sacrificed for a fleeting fee reduction. This represents a different and more compelling political scenario than merely endorsing “free trade in principle.”

Lastly, it is important to focus on measurement. ECAMR should generate an annual “Education Integration Dashboard.”

Build the Coalition That Can Withstand the Bribe

We began with the most critical observation of 2023: Asia generated nearly 70% of the world’s new patents. That is neither a bragging right nor a trivia fact; it is a map of where the region’s durable leverage resides. A tariff-centric “Asian EU” would spend its energy on the world’s most fragile bargaining chip—rivalrous market access—and on the world’s messiest political problem—dividing a lumpy surplus. An education-first compact does the opposite. It grows non-rival public goods, locks them into people and institutions, and allocates benefits through transparent rules that smaller economies can verify and improve against. The last month’s diplomacy—from India–China “partners, not rivals” language to Seoul’s push to normalize ties with Beijing—confirms that Asia’s emerging order will be elastic, overlapping, and domain-specific, not a monolith. Let education be the domain where the region moves first and farthest. The call to action is straightforward: ratify and implement recognition frameworks, commit a tithe from intra-Asian investment to skills development, adopt Shapley-style rules for joint funds, and publish a dashboard that makes backsliding impossible to hide. That is the coalition design that resists the bribe—and turns Asia’s IP engine into shared, compounding power.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Asian Development Bank (2025). Asian Economic Integration Report 2025 — Highlights. Manila: ADB. (Services FDI ≈58%, intra-Asian FDI ≈52%, climate greenfield 8%→27%.)

ASEAN Secretariat (n.d.). Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). (RCEP ≈30% global GDP; >25% of world exports.)

Kawashima, S. (2025, August 31). Ishiba’s China policy increasingly contested after electoral setback. East Asia Forum.

OECD (2024, March). Main Science and Technology Indicators — Highlights. (R&D intensity: Korea ≈5.2% of GDP; Israel ≈6%.)

Reuters (2025, August 24). South Korea tells China it wants to normalise ties, upgrade economic relations. (Reporting by Ju-min Park, Jack Kim.)

Reuters (2025, August 31). India and China are partners, not rivals, Modi and Xi say.

UNESCO (2025, January). Global Convention on the Recognition of Qualifications concerning Higher Education — recent developments and ratifications. (Including Republic of Korea and Mongolia in 2025.)

WIPO (2024). World Intellectual Property Indicators 2024 — Highlights (Patents). (Asia ≈69.7% of global patent grants, 2023.)

WIPO (2024). PCT Yearly Review 2024 — Executive Summary. (Asia ≈55.6% of PCT applications, 2023.)

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2025, January 23). China’s R&D intensity ≈2.68% of GDP in 2024. State Council Information Office release.

ASEAN (n.d.). Framework Agreement on Mutual Recognition Arrangements; Agreements on Services and Movement of Natural Persons.

Comment