The Political Economy of Masculinity Norms: Why Identity Still Moves Markets and Classrooms

Input

Modified

Masculinity norms shape labour supply, health, and political preferences Germany’s 1940s and Korea’s 2020s show contrasting trajectories Education policy can recalibrate norms and stabilise economies

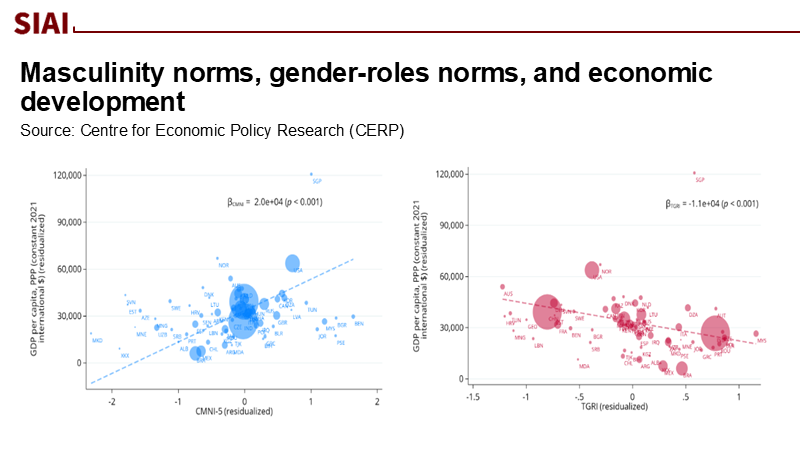

Across 70 countries, a one-standard-deviation rise in men’s adherence to traditional masculinity norms is associated with an 8-percentage-point increase in support for strongman rule, a 4% rise in desired working hours, and measurably worse health behaviours, including higher self-reported risk-taking and lower help-seeking for mental health (new cross-country evidence, 2024–2025). These are not abstract shifts. In late 2024, one of Asia’s most advanced democracies briefly experienced martial law and then an impeachment crisis—a volatile episode that illuminated how quickly political equilibria can bend when identity-charged cues are activated. For educators and policymakers, the point is not to moralize about culture; it is to recognize that norms about manhood are shifting variables with macro-level consequences. Markets price them through labour supply, sectoral risk, and political risk premia. School systems reproduce or redirect them through pedagogy, peer dynamics, and health education. If we want stable democracies and productive, healthy individuals, we must treat masculinity norms as a targetable input in human capital and civic education policy, not a background constant.

The missing variable in human-capital policy

The core reframing is simple: gender norms affecting men—what it means to “be a man,” how to signal status to other men, when to take risks, when to seek help—belong inside the education and human-capital toolkit. The emerging empirical literature shows that masculinity norms carry independent predictive power over and above conventional gender-role attitudes. Using newly harmonized surveys of more than 80,000 men across dozens of countries, researchers measure conformity to norms such as winning, emotional control, risk-taking, dominance, and the primacy of violence. At the individual level, tighter conformity predicts higher desired hours, greater competitiveness, and sectoral sorting into archetypically “male” jobs even when those sectors are shrinking. At the polity level, the same index predicts lower support for democracy and market institutions, and higher support for army rule. The mechanism is not mysterious: in contexts where status is policed through toughness and dominance, admitting uncertainty, switching sectors, or seeking mental-health care carries identity costs. A policy that ignores those costs underperforms.

Two implications follow. First, standard labour-market fixes—reskilling, apprenticeships, career guidance—must be paired with identity-aware design. Programmes that merely offer training leave take-up on the table if the target occupation is coded as “feminine” or low-status; messaging and mentorship must be engineered to recode the move as skilled, challenging, or future-oriented. Second, school-based health and civic curricula must explicitly surface how “don’t show weakness” norms depress help-seeking and raise externalised coping (e.g., alcohol binges), and how peer misperceptions amplify the cycle. Experimental work with adolescents suggests that even light-touch discussions about what peers actually think can halve misperceptions and shift intentions—evidence that the classroom is a viable arena for norm recalibration, not just information delivery.

From militarised masculinity to soft power aesthetics: Germany’s 1940s and Korea’s 2020s

History supplies the cautionary baseline. Interwar and wartime Germany cultivated a state-sponsored ideal of virility—discipline, hardness, contempt for softness—that fused into political liturgy and everyday life. Scholars of that era have long documented how this “modern masculinity” was mobilised to justify violence, suppress dissent, and yoke male status to national destiny. The economic behaviours are legible in retrospect: high tolerance for physical risk, militarised labour mobilisation, and a politics comfortable with hierarchy and command. The point is not to equate then and now, nor to essentialise national character, but to recognise a template: when manhood is performatively tied to dominance, authoritarian preferences gain a cultural runway.

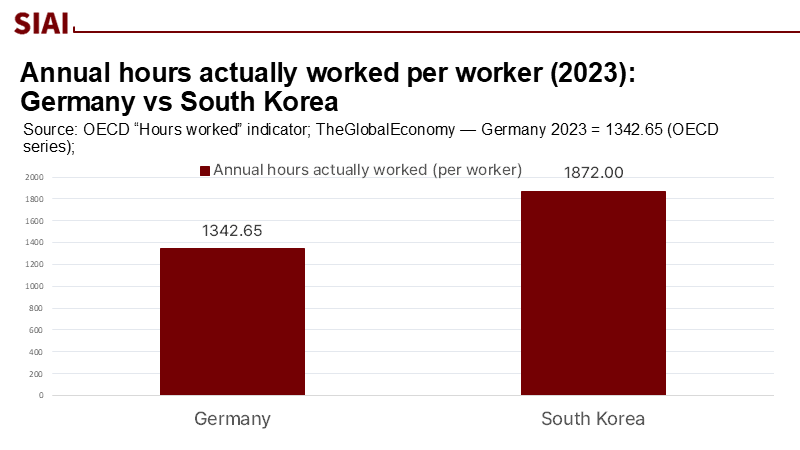

Korea today offers a more ambiguous—and therefore more instructive—contrast. On one track, work intensity is structurally high but falling: average annual hours worked remain well above the OECD mean, yet have declined steadily (Korea c. 1,870 hours in 2023 vs. Germany ~1,343), a sign of gradual recalibration away from the most punishing margins of labour supply. On another track, health behaviours remain concerning and gendered: overall smoking has halved since 2008, but male binge-drinking and male obesity have proved stubborn or risen, particularly in the 20s–40s cohorts. A third track is political: after a brief martial-law decree in December 2024, parliament and the courts reasserted control; by mid-2025, Korea’s democracy indices remained “flawed” but resilient. Layered atop all this is a cultural export of “soft masculinity”—the kkonminam aesthetic of male idols—that decouples male status from brute dominance and broadens acceptable self-presentation. The coexistence of softer aesthetics, persistent high-risk health habits among men, and democratic turbulence underscores the central thesis: masculinity is multidimensional and policy-malleable.

Designing masculinity-savvy education—and why investors should care

If norms shape labour supply, health, and political preferences, then education systems must measure and move them. Start with curricular “masculinity literacy.” In adolescence—the window when status hierarchies harden—students should be taught to recognise how identity costs distort choices: hiding effort to avoid “try-hard” stigma; refusing sectors coded as feminine; equating stoicism with strength. This is not moral instruction; it is choice architecture. Lessons can pair short readings on historical constructions of manhood with local data on health and economic outcomes by gender. A method note: where administrative microdata are not available, schools can run low-burden, anonymous climate surveys using validated short scales (e.g., the CMNI-5 items used internationally), then track shifts semester-to-semester alongside attendance, coursework completion, and counselling uptake.

Next, rebuild help-seeking as a status-consistent act. The same evidence base that links conformity to masculine norms with lower mental-health engagement points to a design fix: message counselling, tutoring, and career-switch services as strategic self-discipline and team reliability, not vulnerability. In practice, that means featuring male alumni (including tradesmen and former athletes) who frame counselling and study skills as performance tools; placing services in settings coded as “doing,” not “waiting” (e.g., integrated within coaching sessions or makerspaces); and training staff to name and neutralise the “show no weakness” script explicitly. A brief method note: track treatment effects via difference-in-differences across cohorts as services are rolled out, using administrative outcomes (credits earned, drop-out, referral completion) while preserving privacy.

Third, recoding sectors, not just skills. Where labour demand requires movement into care, education, or service roles, schools and technical colleges should change the narrative around those jobs. Showcase the precision, teamwork, and risk management inherent in emergency medical care, early-years education, or advanced hospitality; build capstone projects that emphasise logistics, systems thinking, and entrepreneurship within those domains; and align apprenticeship branding with valued masculine scripts like mastery and guardianship. Evidence from cross-country panels suggests that even when men express high competitiveness, they tend to avoid jobs that clash with their identity; rebranding can unlock suppressed supply without coercion.

Fourth, target health behaviours that most throttle male human capital. Korea’s tobacco success shows that norms can move: overall smoking fell to 17.7% by 2022. The more complex problems now sit in alcohol and obesity. High-risk drinking among adult men remains elevated; metabolic syndrome is widespread; obesity among men in their 30s exceeds 50% in some samples. School-to-work transitions are the ideal choke-point: integrate brief alcohol-risk interventions into conscription health checks and university orientations; incorporate strength-and-mobility PE that competes with binge-drinking rituals for male bonding; and create “performance contracts” where cohorts publicly commit to season-long alcohol limits in sports clubs, enforced by peer-agreed incentives rather than top-down punishments.

Fifth, teach political economy as identity economy. A civics unit that names how performative toughness can make emergency powers feel attractive—and how institutions deliberately slow that impulse—equips students to read political theatre without humiliation. Korea’s 2024–2025 crisis can be taught with primary-source timelines, linked to comparative data from democracy indices, to demonstrate how norms and institutions interact under stress. Instructors should require students to write short policy memos on trade-offs in crisis governance, explicitly scoring for the ability to separate identity satisfaction from policy efficacy.

Finally, a note to investors. If masculinity norms shift the distribution of risk appetite, they become a hedging variable. The cross-country evidence associates stronger masculinity norms with both higher individual risk tolerance and illiberal political preferences—a recipe for boom–bust investment climates. In Korea, venture capital flows rebounded in 2024–2025 after contracting in 2022, yet the same period also saw political volatility and a softening of extreme work hours. A pragmatic hedge treats “masculinity intensity” as a factor: in high-intensity locales, favour barbell strategies that overweight regulated defensives (healthcare, utilities) and early-stage options with capped downside; in low-intensity locales where help-seeking and institutional trust improve, expand exposure to human-capital-heavy services. None of this is destiny; it is probability management in a world where identity shifts move both cash flows and constitutions.

One objection is that norms talk pathologise men or stereotype countries. The remedy is measurement and heterogeneity. The best studies show wide within-country dispersion and separate effects of masculinity norms from generic gender attitudes; they also find ambivalence: more hours and competitiveness can be growth-supportive in the short run, even as illiberal preferences raise long-run political risk. Another objection is that structural constraints—such as wages, childcare, and housing—drive behavior far more than norms. True. But the policy choice is not either/or. Germany’s very low annual hours relative to the OECD reflect institutions, tax design, and demographics; yet identity-aware nudges still help men cross sectoral boundaries or use counselling without stigma. A final concern is feasibility: can schools implement such comprehensive scripts? Early adolescent experiments suggest that, indeed, this is the case, through peer-norm correction and by teaching that toughness encompasses care for teammates and oneself. The point is not to engineer character but to widen the menu of dignified male behaviours.

A modest increase in conformity to masculine norms shifts political preferences, labour supply, and health behaviour in measurable ways. In a decade where multiple democracies have flirted with emergency rule, and where post-industrial labour markets demand sectoral pivots, silence about masculinity is a policy choice with costs. We have tools—validated scales to measure norms, classroom protocols to correct misperceptions, identity-aware messaging that recodes help-seeking and sector switches, and capstone projects that align mastery with prosocial goals. We also have comparative guardrails: history’s account of militarised masculinity; Korea’s present blend of softer aesthetics, persistent male health risks, and democratic muscle memory; Germany’s structural hours vs. productivity debate. The call to action is practical: build masculinity literacy into curricula, recode services to fit male identity without pandering to dominance, and evaluate like economists. If we do, we can convert a volatile identity variable into a stable asset—stronger classrooms, steadier labour markets, and democracies less vulnerable to the next “strong man” promise.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Baranov, V., De Haas, R., Grosjean, P., & Matavelli, I. (2024). Masculinity Norms: International Evidence and Implications for Economics, Health, and Politics. Working paper (cross-country evidence).

Baranov, V., De Haas, R., & Grosjean, P. (2023). “Men: Male-biased Sex Ratios and Masculinity Norms—Evidence from Australia’s Colonial Past.” Journal of Economic Growth, 28, 339–396.

Economist Intelligence Unit. (2025). Democracy Index 2024. London: EIU.

Financial Times. (2025). “South Korea’s Real-Life Political Drama” (Rachman Review podcast transcript). FT.com.

Guardian. (2025, Jan. 6). “After a month of political chaos, where does South Korea go now?” The Guardian.

Jung, S. (2010). Korean Masculinities and Transcultural Consumption. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA). (2024, Dec. 23). 2023 KNHANES Key Findings (press release highlights: drinking, physical activity, obesity trends).

Mahalik, J. R., et al. (2003). “Development of the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory.” Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 4(1), 3–25. (Foundational scale referenced by subsequent work.)

Ministry of SMEs and Startups (Republic of Korea). (2025). “Venture Investment Trends: 2024 rebound; Q1 2025 momentum.” MSS press releases.

Mosse, G. L. (1996). The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity. Oxford: OUP. (Historical analysis of militarised masculinity.)

OECD. (2024). Economic Surveys: Korea 2024 (hours-worked trend). Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2025). “Hours worked—Indicator” and data explorer (Germany and Korea, 2023 values). Paris: OECD.

Park, K.-Y., et al. (2024). “Tobacco Control Policies in Korea: 30 Years of Progress and Remaining Challenges.” Journal of Korean Medical Science, 39. (Smoking rate fell to 17.7% in 2022; ~50% decline since 2008.)

Reuters. (2024, Dec. 3). “South Korea Issues Martial Law Decree: Full Text & Timeline.” Reuters.

World Values Survey Association. (2024). WVS Wave 7 Online Analysis Tool (items on “strong leader without parliament” and democratic support).

Yoo, J.-J., et al. (2024). “Trends in Alcohol Use and Alcoholic Liver Disease in South Korea.” BMC Public Health. (High-risk drinking stable overall; age-sex heterogeneity.)

Comment