Tariffs Are Taxes—And the Bill Lands at Home

Input

Modified

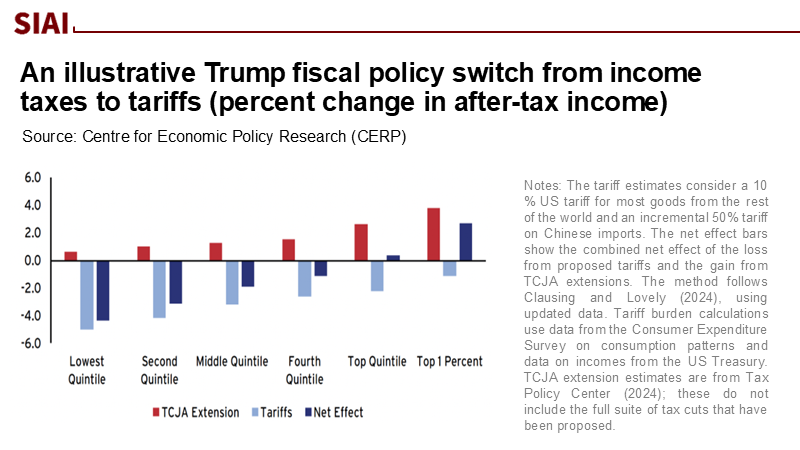

Tariffs act as hidden taxes, falling mainly on U.S. firms and households The burden is regressive, shrinking lower-income purchasing power the most Education budgets face rising costs while revenues lag

The most critical number in today’s tariff debate is not the headline rate splashed across press releases, but 0.4—the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of how much this year’s tariff wave is likely to add to annual inflation in 2025 and again in 2026. That looks small until we translate it: for a median household, 0.4 percentage points is roughly a week of after-tax pay erased without a single line showing up on a paycheck stub. It is also a tax whose burden falls where the evidence says it always has in recent U.S. episodes—here at home. The U.S. International Trade Commission’s post-mortem of the 2018–21 measures found import prices rose one-for-one with tariff rates, meaning U.S. importers (and then their customers) paid nearly the entire levy. Add a new 2025 surge on top of that base, and the arithmetic is plain: the government’s balance sheet may look better, but the household and school balance sheets many readers manage will not.

From Visible Tax Cuts to Hidden Tax Hikes

The current policy pivot substitutes a visible debate over income-tax rates with a quieter shift toward consumption taxes collected at the border. Independent estimates converge on the same order of magnitude. One respected model pegs the 2025 tariff package as an average tax increase of nearly $1,300 per household this year, while academic budget labs estimate short-run price-level effects in the 1.8–2.3% range depending on the exact mix and timing of measures. Those figures come from standard pass-through assumptions, not exotic theory: when the border tax goes up, so do landed costs; when inventories roll off, checkout prices follow. For an education system already squeezed by wage catch-up, utilities, and insurance premiums, that is not an abstraction. It means device carts, science lab kits, cafeteria inputs, school buses, and roof repairs cost more before a single new program is approved.

Distribution matters as much as size. Tariffs are regressive because they fall on goods consumed across the income distribution—clothing, footwear, household staples—rather than on concentrated capital income. Even if the headline goal is fiscal consolidation, border taxes worsen the ratio of tax paid to income at the bottom. That trade-off is not conjecture: the same budget scorekeepers who note tariff revenue gains also warn that the boost to receipts comes with slower growth, higher prices, and lower real incomes, especially in the near term. Suppose the policy intent was to restore balance by taxing domestic high earners more. In that case, the practical effect of relying on tariffs is the opposite: a broad-based levy that touches the checkout line long before it touches capital gains. For education administrators and state finance directors, this is the operational definition of a squeeze: revenues lift modestly; input costs lift faster.

The sectoral channels make the point concrete. Where schools build, renovate, or expand, steel and aluminum costs loom large; the trade commission’s technical appendices document near-complete pass-through on these metals when tariffs rose last cycle. When schools procure technology, the policy design—raising rates on electronics, batteries, and semiconductors in 2024–25—directly impacts device and component budgets. A district refreshing 1,500 Chromebooks or outfitting a new STEM lab cannot shop its way around an economy-wide border tax; it can only defer purchases, reduce quantity or quality, or ask taxpayers for more. Those are policy choices hiding in procurement spreadsheets. They are also the kinds of second-order impacts that do not show up in simple “Made here” talking points.

Who Pays, Precisely? Evidence From Pass-Through and Early-2025 Data

If there is one empirical regularity in the modern tariff literature, it is incidence. Studies of the 2018–19 measures—using border microdata and scanner-level retail prices—found near-full pass-through to U.S. import prices and, depending on the category, partial to substantial pass-through to retail prices. One influential estimate projected that the monthly cost to U.S. consumers and importing firms would reach billions of dollars by late 2018 alone, with domestic producers in tariff-protected sectors raising their own prices under the umbrella. The trade commission’s 2023 synthesis landed at almost the same place: roughly 1% price increase for each 1% tariff, on average, across key programs. Method note: these results are identified by comparing price changes for tariffed vs. untariffed HS lines before and after policy moves, controlling for time and product fixed effects. This conservative approach tends to minimize the likelihood of finding significant effects.

The early tape of 2025 looks consistent with that history. As inventories accumulated during the pre-tariff lull cleared, retailers began to telegraph price increases on everyday items—from canned goods to hardware—explicitly citing import costs and new duties. Macro prints, too, are starting to show import-price-led pressure in core inflation gauges even as overall demand cools, a pattern consistent with cost-push rather than overheating. None of this says every cent is passed through instantly; it says the direction is up, and the stickiness is asymmetric when input costs rise faster than they fall. Education budgets will feel that asymmetry as fall procurement meets winter price sheets.

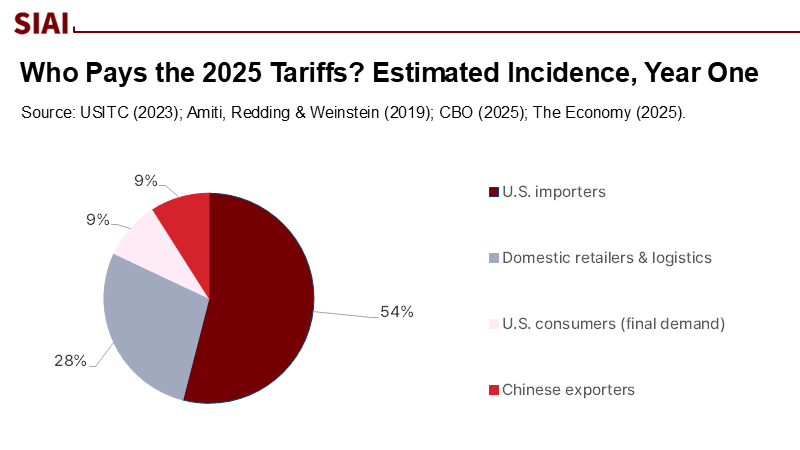

International burden-sharing is often misunderstood. New reporting this week, synthesizing sell-side estimates and supply-chain interviews, suggests Chinese exporters are currently shouldering roughly 9% of the latest tariff costs, with U.S. importers bearing more than half and final consumers another 8–10%—the rest absorbed in thinner margins along the U.S. retail and logistics chain. That is consistent with the earlier research consensus that large-country tariffs did not significantly depress foreign export prices in practice. The details track the real economy: Multinationals pushed for supplier burden sharing, but suppliers resisted. As a result, some production was migrated to third countries for final assembly, and a significant portion of the tax still ended up on U.S. ledgers. Schools, in turn, buy the same desks, tablets, and HVAC components that households do. If we insist on treating tariffs as a free lunch, our procurement officers will keep proving otherwise.

The policy landscape compounds these pressures. Last year’s rate hikes on strategic inputs—EV-related batteries, solar modules, and semiconductors—were justified as industrial policy. This year’s broader additions add a fiscal-balance logic. Combine the two, and you have an instrument calibrated for revenue and political signaling, rather than cost minimization for downstream users, such as districts and universities. Revenue projections for a universal tariff or China-specific surcharges are large on paper, but those dollars are not frictionless. They are collected via markups in construction bids, cafeteria contracts, and IT procurement, and then partially recycled through higher state and local appropriations or higher tuition. It is, in effect, a round trip through the real economy with leakage.

Policy Choices That Protect Learners Without Pretending Tariffs Are Free

If we accept that tariffs function as taxes—and that most of the burden is domestic in the short run—then the policy problem is to neutralize the harm where it is most regressive while preserving room for narrowly tailored strategic trade actions. First, set explicit sunset and review clauses on broad-based measures, with automatic ratchets down absent a documented market-power or national-security finding. Second, treat the revenue honestly: a share should be earmarked to offset higher prices for public-interest purchasers. In K-12 and higher education, that means a tariff offset formula tied to procurement baskets with high import content—devices, lab equipment, cafeteria staples, bus parts—and delivered automatically through Title I, IDEA, and Pell adjustments rather than ad-hoc grants. This is not a special-pleading carve-out; it is standard tax-incidence hygiene. The same budget analysts who track receipts also account for the losses in real purchasing power. The point of policy is to see both columns.

Third, prefer narrow, time-bound safeguards and remedies over across-the-board rates. If the aim is to deter dumping or subsidized capacity in a specific sector, use the statutes designed for that job and pair them with procurement and standards policies that accelerate domestic substitution—buy-down vouchers for approved, interoperable devices; open-architecture science kits; building codes that reduce steel intensity. Where the goal is revenue, say so, and then design the revenue instrument with distribution in mind—a modest surcharge on high-income capital income raises money with less damage to the school-lunch line than a 15% duty on apparel. For administrators, the practical guidance is immediate: revisit three-year procurement calendars, insert tariff pass-through clauses and transparent price-adjustment schedules in contracts, pre-qualify multiple vendors in tariff-sensitive categories to preserve competition, and build a contingency line item keyed to a published tariff index so boards are not forced into mid-year cuts.

Finally, there are costs we have not priced here because they unfold off-budget—lost diplomatic leverage, retaliation risks that squeeze export-exposed regional economies, and the chilling effect of policy volatility on private investment. These externalities are real, even if they resist simple scoring. They matter for education because state budgets are cyclical; when regional exports slow, local revenues soften, and the first casualties are capital plans and hiring lines. The immediate job, then, is twofold: discipline tariff policy to minimize avoidable domestic harm, and firewall essential learning services from the inflation it does create. We can do both if we stop pretending tariffs are pain-free and start governing them like the taxes they are.

The argument can be stated in one line: the 2025 tariff wave is best understood as the most significant general-consumption tax increase in a generation, and its burden is falling primarily on U.S. firms and families rather than foreign producers. The cross-checks—trade-commission pass-through estimates, household-level cost models, and the first price moves from retailers—are all pointing in the same direction. Suppose the political promise was to restore balance by taxing at the top. In that case, the policy reality is a broad-based levy that quietly drains purchasing power from classrooms, cafeterias, and campus maintenance. We do not need to litigate every strategic aim to fix that mismatch. We need sunsets, offsets, and specificity: sunset broad tariffs unless renewed on evidence; offset the regressivity where public missions are at stake; and shift from sweeping rates to targeted remedies when market power—not revenue—drives action. The number that opened this essay—0.4—deserves to close it as a warning: left unmanaged, incremental adds up. The correct course of action now is to govern tariffs as taxes, prioritize protecting learners, and make fiscal honesty a feature, not an afterthought.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Amiti, M., Redding, S. J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2019). The Impact of the 2018 Tariffs on Prices and Welfare. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(4), 187–210. (See also NBER Working Paper No. 25672.)

Congressional Budget Office. (2025a). Budgetary and Economic Effects of Increases in Tariffs Implemented in 2025. Washington, DC.

Congressional Budget Office. (2025b). An Update About CBO’s Projections of the Budgetary and Economic Effects of Tariff Increases. Washington, DC.

Clausing, K. (2025, August 29). The aftermath of tariffs. VoxEU (CEPR).

The Economy. (2025, September 2). Chinese Exporters Shoulder Just 9% of ‘Trump Tariffs,’ Leveraging Supply Chain Dominance to Exert Influence.

Reuters. (2025, August 29). U.S. consumer spending strong in July; core inflation firmer.

Tax Foundation. (2025, April 10). How Much Revenue Can Tariffs Raise? Washington, DC.

Tax Foundation. (2025). The Economic Impact of the Trump Trade War (2025 update). Washington, DC.

U.S. International Trade Commission. (2023, March 15). Press release: Certain effects of Section 232 and 301 tariffs reduced imports; raised prices approximately one-for-one. Washington, DC.

U.S. International Trade Commission. (2023). Economic Impact of Section 232 and 301 Tariffs on U.S. Industries (Pub. 5405). Washington, DC.

White House. (2024, May 14). Fact Sheet: President Biden takes action to protect American workers and businesses from China’s unfair trade practices. Washington, DC.

The Wall Street Journal. (2025, August). Higher Prices Are Coming for Household Staples.

Yale Budget Lab. (2025, April 2). Where We Stand: Fiscal, Economic, and Distributional Effects of All U.S. Tariffs Enacted in 2025 (through April). New Haven, CT.

Yale Budget Lab. (2025, August 7). State of U.S. Tariffs: August 7, 2025. New Haven, CT.

Comment