The Suffocation of “Efficiency”: What Germany’s Red Tape Teaches Education Reform

Input

Modified

Germany’s reputation for efficiency hides massive losses from excessive bureaucracy Evidence from trains, bakeries, and schools shows that cutting redundant processes boosts performance and retention. Education systems can reclaim thousands of teacher-hours by pruning forms and trusting professionals

A single number should concentrate the mind: €146 billion. That is the ifo Institute’s upper-bound estimate of the annual output Germany forfeits to bureaucracy—lost hours, delayed permits, duplicated reporting, compliance rituals that rarely change a decision. It is more than most European education budgets combined, and it sits at the heart of a nation long mythologized for punctuality and order. If a system with Germany’s reputation can bleed that much capacity through paperwork, the warning is universal: process has outgrown performance. Education, a sector that often mirrors the administrative habits of its host state, should treat this as a mirror. Forms do not equal safety. Checklists do not equal quality. Control does not equal competence. The policy task is not anarchic deregulation; it is precision regulation—fewer, testable rules; digital plumbing that actually works; and discretion where the work is done. The dividend is time, retention, and better outcomes.

Excessive Bureaucracy Is Not Discipline—It Is Friction

Reputation and reality have parted ways. In 2024, only 62.5% of Germany’s long-distance trains met Deutsche Bahn’s six-minute on-time standard, the worst result in decades—a highly legible sign that coordination and maintenance have been crowded out by complexity. Euro 2024 showcased the contrast: the tournament venues functioned; the rail backbone wobbled. Germany’s transport minister publicly conceded that the system “fell short” of expectations amid widely reported delays. When the country that coined the term Gründlichkeit struggles to move people on schedule, the problem is not a lack of effort; it is friction. Education systems operate in the same weather: delayed school repairs, stalled reimbursements, identity checks that cannot communicate with one another, and portals that require schools to re-enter data the state already holds.

The broader digital state tells a similar story. In the eGovernment Benchmark 2024, the leaders are Malta and Estonia, followed by Luxembourg and Iceland—small states that have built “once-only” data flows and pre-filled forms into the architecture of their public services. Germany’s progress is real yet uneven, and where portability and pre-filling lag, citizens and institutions pay in time. The point of education is simple: when platforms remember people, compliance stops devouring instruction. When they do not, administrators become clerks with classrooms attached to them.

Bureaucracy’s defenders are not entirely wrong: rules prevent tail risks and protect equity. But the economics of rule accumulation turn sharply negative when obligations multiply faster than benefits. In March 2025, German executives told Reuters that new investment would underperform unless red tape is cut alongside spending—a sentiment echoed by the government’s own Bureaucracy Relief Act IV (BEG IV), which shortens retention periods and nudges digitization. If firms drop automation projects because compliance wipes out the case for change, schools will do the same with promising learning tools. That is not prudence; it is a misallocation of attention.

From Trains to Bakeries: What the Data Actually Shows

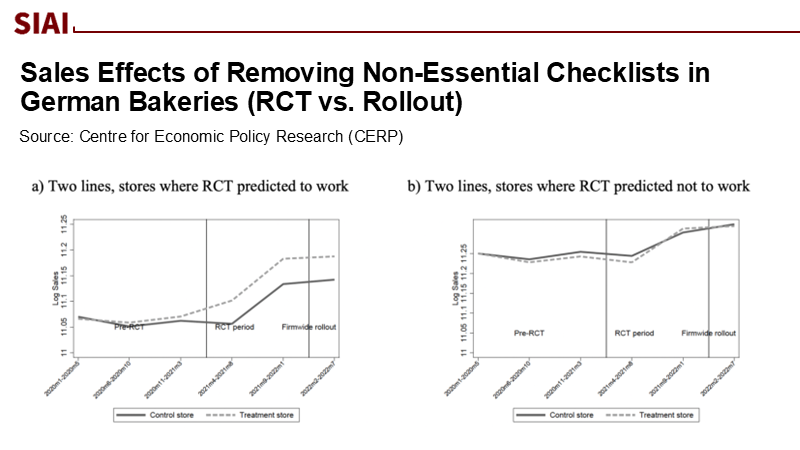

Macro-signals can be dismissed as “too complicated.” Micro-evidence is harder to wave away. A recent randomized controlled trial in a German bakery chain removed two time-consuming, non-essential checklists in half the stores. The result: sales rose by 2.7%, customer ratings improved, and manager turnover fell—with no uptick in measurable problems. The mechanism matters: skilled staff resented bureaucratic steps that neither improved product quality nor changed any decision. When those steps disappeared, effort shifted to the work that counts. Translate that to schools and colleges, and the analogy is direct. If a form does not alter a judgment or prevent a material risk, it is a candidate for retirement or one-click automation.

There is a physical corollary to administrative waste: heat literally vented to the sky. Industrial “bread factories” that install oven waste-heat recovery routinely report double-digit energy savings; one bread-pan line retrofit documented around 20% lower energy use after re-engineering the thermal envelope and recovering exhaust heat. Peer-reviewed work from 2023–2024 details practical recovery schemes and credible paybacks for commercial bakeries. None of this is glamorous. It is incremental housekeeping in which capacity appears the moment waste is removed. In education, classroom hours and budget headroom are thermal energy by another name. When we stop venting them up the compliance chimney, we regain the power to tutor, plan, and support.

Pull back to the state. By late 2024, the ifo estimate put the macroeconomic drag of bureaucracy at up to €146 billion annually; by mid-2025, the political and business consensus had converged on the need for measurable simplification, not cosmetic digitization. The eGovernment Benchmark tells us what to measure: online availability, pre-filled forms, cross-border identity, and back-end interoperability. When those indices move, user time falls. And when user time falls, frontline staff stay. Retention is an outcome of respect; nothing communicates respect like a portal that does not make you retype your name.

Education’s Red-Tape Dividend: A Practical Agenda

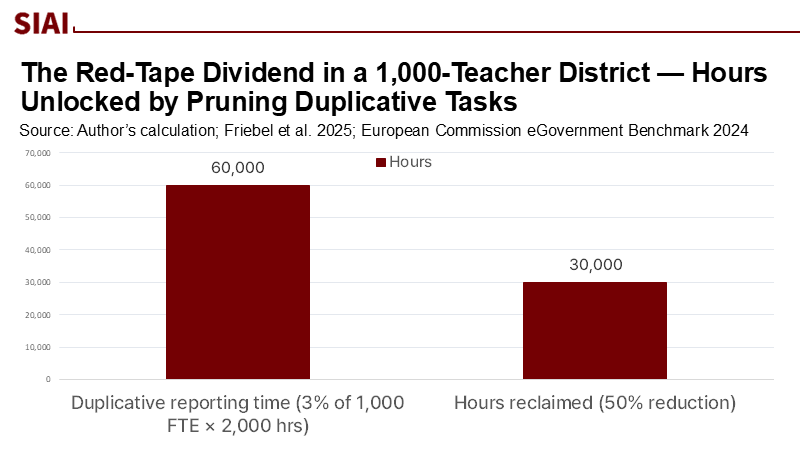

Start with a conservative thought experiment. Suppose teachers and school leaders spend 3% of working time on duplicative reporting—double entry, uploads to multiple portals, forms that ask for data the state already has. In a district with 1,000 full-time educators working 2,000 hours a year, that is 60,000 hours of compliance. Reclaiming even half yields 30,000 hours—roughly 18 full-time equivalents—available for small-group instruction, student feedback, or mentoring. Method note: hours = FTEs × annual hours × burden share × reclamation rate = 1,000 × 2,000 × 0.03 × 0.5 = 30,000. The salary money already exists; the dividend materializes when we eliminate work that does not need to be done.

Next, replace blanket checklists with risk-weighted controls. The bakery RCT worked because the removed checklists were non-essential. Aviation and surgery keep theirs; schools should keep robust safeguarding, finance, and equity controls. But lesson-template mandates, attendance justifications already captured by the student-information system, or procurement paperwork for trivial items are ripe for elimination or automation. The test is practical: if a form does not change a decision pathway or avert a significant, named risk, it should be retired, consolidated, or pre-filled. Pilot “checklist amnesties” across a randomized set of schools for one term, then track error rates, teacher satisfaction, and student outcomes. That is how you learn which controls are actually doing work.

Then make “once-only” a rule with teeth. The EU’s once-only principle says citizens and firms should provide data just once; the government should re-use it across agencies. Education systems can adopt the same stance immediately: a single sign-on that pre-fills HR, payroll, and student data; a ban on any department requesting information that the state already holds; and a quarterly dashboard showing the percentage of forms pre-filled and the number retired. Tie leadership bonuses to those metrics. If national reform stalls, consider implementing it at the district or university level and publish the resulting time savings. Policy that is not measured is poetry.

Fourth, institutionalize pruning. Bureaucracy accretes because there is no routine for subtraction. Borrow from capital budgeting: every new compliance obligation should carry a sunset clause, plus a standing “repeal-two” rule for process additions above a low threshold. Where legal constraints prevent repeal, require consolidation, and pre-filling. Crucially, treat removal itself as a reportable performance metric: departments should publish how many forms they deleted, how many fields they pre-filled, and the measured time-to-completion for the top ten tasks. After a year, roll the results into funding formulas.

Fifth, fund plumbing, not dashboards. The eGovernment Benchmark’s most useful finding for education is pedestrian but decisive: pre-filled forms and mobile-ready portals reduce friction; flashy analytics do not compensate for broken identity and messy data. Negotiate procurement contracts that penalize any vendor demanding manual re-entry of state-held data. Require live service-level agreements for uptime and form-completion times. The goal is quiet competence, not a new visualization layer on top of a clunky process.

Sixth, flatten HR and empower “cells.” Thin, cellular structures—small units with clear missions and high autonomy—cut the need for upstream micromanagement. In schools, that means departmental teams with delegated budgets, short escalation paths, and transparent service commitments from central offices. Germany’s business community is asking for the same in the macro-economy: invest, yes, but cut the procedural drag that nullifies the investment case. Education should take the lead: align compliance with outcomes, publish the non-negotiables, and stop issuing one-size-fits-all process memos. Measure outputs; let leaders choose inputs.

Finally, harvest the energy analogy. Treat teacher time like kilowatt-hours. The industrial bakery literature indicates that there is money on the table when you stop wasting usable heat. The school-system version is all the micro-process waste we normalized during the past decade of “platformization.” A focused process audit—ten forms, one term—will usually find two or three that deliver near-zero marginal value. Remove them and the capacity appears—as surely as heat exchangers trim a bakery’s gas bill. Document the gain in hours, and roll it forward.

Suppose Germany loses €146 billion a year due to friction. In that case, the world’s school systems are almost certainly burning a comparable share of their human capital on rituals that do not protect, inform, or improve. The last year has stripped away the romance around “German efficiency.” Fans at Euro 2024 learned that trains and schedules do not obey stereotypes; executives have told ministers that forms and inspections will deter investment unless they are streamlined; the rail statistics have embarrassed a national icon. None of this indicts German workers or administrators. It suggests that more process means more safety. In education, the cost is paid in attention: fewer minutes for explanation, fewer loops of feedback, fewer conversations with families. The path out is also clear. Audit the top ten forms. Run a randomized checklist amnesty. Wire identity and data so the system remembers people. Set public targets for pre-filled forms and retired paperwork. Publish the hours you give back. Then spend them where they matter most: tutoring, planning, mentorship, and time for teachers to be professionals. Efficiency is not the enemy of rigor; excessive bureaucracy is. Our call to action is practical and measurable: prune, pre-fill, pilot, and trust—and count the hours you win back.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Capgemini; European Commission DG CONNECT. (2024). eGovernment Benchmark 2024 Insight Report.

European Commission. (2024). Digital Decade: eGovernment Benchmark 2024.

Friebel, G., Heinz, M., Hoffman, M., Kretschmer, T., & Zubanov, N. (2025). “Detecting potentially harmful workplace practice.” VoxEU/CEPR column.

Friebel, G., Heinz, M., Hoffman, M., Kretschmer, T., & Zubanov, N. (2025). Is This Really Kneaded? Identifying and Eliminating Potentially Harmful Forms of Workplace Control. CEPR Discussion Paper DP20517; NBER Working Paper 34122.

ifo Institute. (2024). “Bureaucracy in Germany costs up to €146 billion a year in lost output.” Press release.

RailTech. (2025, Jan 8). “DB posts worst long-distance delay figures in decades.”

Reuters. (2024, Jul 12). “German railways fell short during Euro tournament, transport minister says.”

Reuters. (2025, Mar 10). “Forms, inspections, reports: German businesses beg for bureaucracy relief.”

Ríos-Fernández, J. C., et al. (2024). “Residual energy use and energy-efficiency improvement of bakery ovens.” Heliyon.

Spooner Food Equipment. (n.d.). “Spooner bakes up 20% energy saving—12,000 loaves/hour bread pan oven (case study).”

TwoBirds (Bird & Bird LLP). (2025). “Germany: Bureaucracy Relief Act IV (BEG IV).”

Comment