Magnanimity Works: Why Education Diplomacy, Not Coercion, Is China’s Credible Path to Taiwan

Input

Modified

Coercion hardens Taiwan’s views; education diplomacy builds trust Extend China’s regional magnanimity to Taiwan with visas, credit recognition, scholarships, and joint labs Protect academic freedom, track mobility and co-production, and scale successes to shift opinion

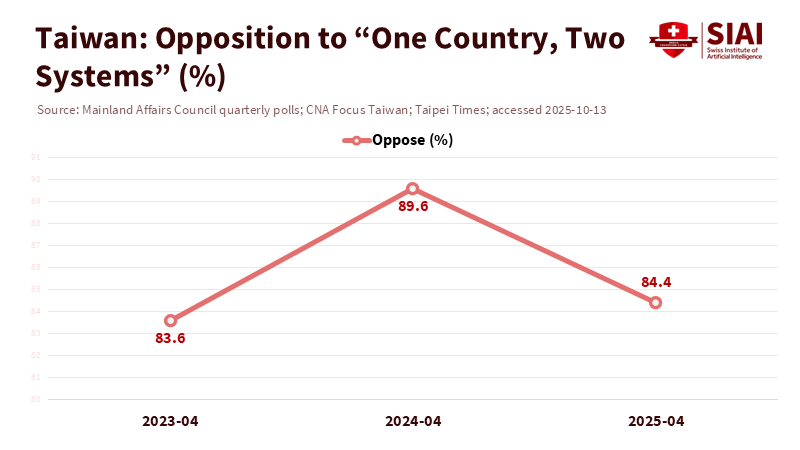

One statistic should stop every strategist in their tracks. In April 2025, 84.4 percent of people in Taiwan rejected “one country, two systems.” That level of resistance has barely changed for years. It is a strong stance in public opinion. Strong opinions do not change with louder threats or bigger military drills. They change through trust, contact, and the slow process of shifting incentives. Education diplomacy is the only tool that can alter attitudes on a large scale without backlash. It is also the only tool Beijing has effectively used with others. China lifted wine tariffs on Australia and restored some goodwill; it signed visa-free agreements with neighbors to ease tensions. Yet, toward Taiwan, the tone remains harsh and the restrictions severe. The difference is striking. If Beijing wants genuine support rather than just media attention—and if Taipei wants engagement without losing autonomy—the next phase must focus on education diplomacy: visas, campuses, labs, and student exchanges, governed by clear guidelines.

From coercion to consequences: the limits of force

Coercion is clear. It also fails to achieve its goals. Beijing’s rhetoric toward Taipei has remained aggressive. As recently as October 2025, China’s foreign ministry criticized Taiwan’s elected leadership using harsh language and portrayed the cross-strait issue as an internal matter. This language shows determination but does not influence voters who care about safety, dignity, and daily travel. It fuels worries and reinforces the belief that dialogue is impossible. In short, it strengthens the existing situation. Meanwhile, Taiwan’s leaders continue to enhance air-defense plans and increase defense spending, a logical response to ongoing military pressure. Coercion leads to counter-coercion and deepens the mistrust.

Public sentiment confirms this trap. The percentage of people in Taiwan who oppose “one country, two systems” has remained in the mid-80s for three consecutive years. Identity trends also work against Beijing’s goals: surveys show a long-term rise in the number of residents who identify exclusively as Taiwanese. When people have strong views, more threats do not change them; they make them firmer. This is why the status quo continues to win elections in Taiwan and why defense budgets continue to rise. Threats may change behavior slightly (like in procurement or training), but they do not change minds.

Coercion also limits the channels that shape long-term attitudes—like travel and education. Since 2019, individual travel from the mainland to Taiwan has been suspended; tour groups have not fully recovered since the pandemic. At times, Taipei has warned its citizens against traveling to the mainland for safety reasons. The outcome is less contact, fewer shared spaces, fewer joint projects, and fewer opportunities for people to build trust. When contact decreases, rumors increase. That creates fertile ground for misinformation and poor conditions for any future political settlement.

Beijing’s “friendly neighborhood” shift—except for Taiwan

Here lies the puzzle. In the region, Beijing has shown that taking a friendlier approach works. With Australia, China rolled back punitive trade barriers. Barley tariffs were removed in 2023. Wine tariffs—previously as high as 218 percent—were lifted in March 2024. Dialogue resumed. Exports started to pick up. The overall tone improved. These are significant steps. They illustrate how economic generosity can undermine aggressive narratives abroad and create opportunities for cooperation.

A similar softening is evident in mobility in parts of Southeast Asia. China and Thailand made mutual visa-free travel permanent as of March 1, 2024. China also expanded visa-free policies for a growing number of countries as part of a broader “friendly neighborhood” initiative. Travel fosters exposure. Exposure fosters empathy. These moves were not just symbolic; they increased the flow of people and showed that China can take practical steps when the benefits are clear. In April 2025, official media described Xi’s Southeast Asia trip as a renewed commitment to “friendship, sincerity, mutual benefit, and inclusiveness” in neighborhood diplomacy.

But toward Taiwan, benefits rarely come without associated threats. Beijing has hosted hundreds of business events aimed at the Taiwanese sectors. Yet, it has paired this friendliness with military drills and harsh messaging. The mixed signals weaken the benefits of engagement. Businesses may attend trade fairs, but the public senses the underlying tension. In a democracy, public opinion is the key factor that matters most for any major cross-strait project. Suppose the “friendly neighborhood” approach works with Canberra and Bangkok. In that case, it makes sense to try a clearer version with Taipei, especially in the one area where results can come quickly and last: education.

Education diplomacy as the key to change in cross-strait relations

Education diplomacy is not just a catchphrase. It encompasses a range of policies that reduce barriers for study, research, and training, supported by enforceable safeguards. It has three advantages in the context of Taiwan. First, it expands without using force. Second, it changes the nature of contact to include younger, undecided groups. Third, it fosters cooperation in areas like science, health, design, and business, where collaboration is mutually beneficial.

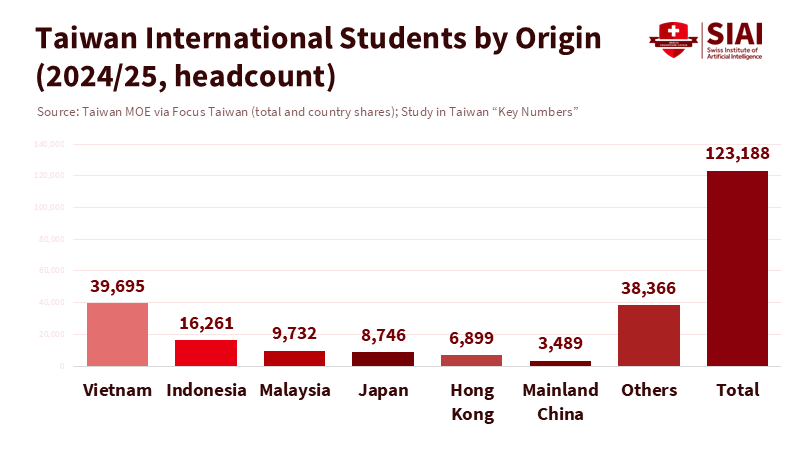

The starting point is weak but not nonexistent. The number of mainland students in Taiwan and Taiwanese students in the mainland dropped sharply during the pandemic and amidst political tensions. By 2024/25, Taiwan hosted about 123,000 international degree students from various countries, but only a small number came from the mainland (approximately 3,500), down from previous highs. Exchange programs are less common than before. Tourism has not returned to previous levels, despite some reopening in specific corridors like the “mini-three links” ferries that connect Kinmen to Xiamen, which saw over one million passenger trips in 2024. This corridor is a ready-made bridge for short courses, joint labs, and internship opportunities.

Now, imagine a targeted pivot based on five clear changes. First, mutual multi-entry education visas are valid for the duration of a degree or research contract, with 90-day visa-free entry for accredited academic events. Second, reciprocal recognition of credits and qualifications in Fujian and Taiwan, based on the PRC’s 2023 Fujian integration blueprint but implemented through a bilateral agreement that guarantees academic freedom and prohibits political vetting. Third, joint scholarship programs—let’s say 1,000 awards each year for STEM, health, and education majors—co-funded by governments and industries. Fourth, a cross-strait PhD cotutelle program for jointly supervised and archived theses. Fifth, a neutral arbitration panel for academic disputes, led by international deans, to keep politics out of lab management. None of this requires Taiwan to concede on sovereignty, and none of it prevents Beijing from stating its claims. It simply asks that both sides prioritize learning over posturing.

There is precedent. Beijing has launched a 50,000 Students initiative to attract American learners back after years of declining exchanges. The same principle applies across the Strait: if personal connections can stabilize relations with a competitor, they can also soften perceptions with a neighbor. In Southeast Asia, Beijing used visa waivers to ease tensions; the educational equivalent is to remove paperwork barriers for labs and classrooms. Applied to Kinmen and Xiamen, education diplomacy could transform a ferry route that currently serves short trips into a channel for semester-long placements and industry apprenticeships in fields like semiconductors, batteries, and health tech.

Risks, safeguards, and how to track progress

The key concern is security. The public in Taiwan perceives a persistent risk of CCP infiltration, and recent issues with IDs and travel warnings have kept worries at the forefront. Beijing also faces trust issues tied to human rights that could affect education: exit bans and arbitrary travel controls on the mainland are legitimate worries for any student or scholar. Education diplomacy will fail if students do not feel safe. It will fail if freedom of speech is restricted or content is filtered. The solution lies in governance, not disengagement.

Safeguards should be clear and mutual. Freedom of speech and research at host institutions must be included in exchange agreements. Academic content should be made available online in advance, with syllabi and datasets mirrored on servers in both regions. Students must maintain their legal rights in their home country. There should be no political loyalty tests, no vetting of family backgrounds, and no repercussions for attending lectures or publishing findings that some officials might not like. A bilateral hotline managed by ombuds offices in each education ministry should handle complaints, with specific time frames for investigations. This strategy does not depend on trust; it creates it through reliable processes.

What does success look like? Three clear indicators. First, mobility. Monitor year-one changes in the number of students traveling both ways, semester exchanges, and short courses. Taiwan already tracks international students carefully; creating a cross-strait dashboard would be straightforward. Second, co-production. Count co-authored papers in applied fields, joint patents, and cross-registered startups—third, attitudes. Monitor quarterly indicators from the MAC regarding perceived friendliness and “one country, two systems,” as well as the percentage of young people who view cross-strait interactions as opportunities rather than risks. Even small changes count. An increase of just five percentage points in perceived friendliness among 18- to 29-year-olds is a significant achievement.

Education diplomacy also provides both sides a way to deal with structural shocks. Taiwan’s export share to China and Hong Kong fell to a 23-year low of 31.7 percent in 2024 as supply chains shifted. That trend is unlikely to change soon. Creating human-capital connections can help maintain economic benefits without relying on fragile trade flows. It can also change the narrative from focusing on warships to centering on grants and graduates.

Expecting resistance. Some may argue that Beijing already employs “carrots”—subsidies for Taiwanese businesses, job fairs, and Fujian incentives—and that these have not changed opinions. That is true. But those “carrots” are combined with sticks, and they often favor the elite. Education diplomacy may involve smaller monetary investments but has a broader social impact. It targets students, teachers, nurses, programmers, and school leaders—the same networks that shape norms. Others may warn that any deepening of ties could lead to manipulation. That risk is real; this is why the model relies on clear rules, transparency, and the option to suspend programs if terms are broken. Finally, some may claim that deterrence, rather than dialogue, maintains peace. Deterrence is necessary, but so is the social foundation that reduces the likelihood of miscalculations. One does not replace the other; they support one another.

A practical beginning. Start where the politics are simplest: short, skill-based programs that provide clear public benefits. Training for nursing in aging societies, battery safety for greener transport, and AI safety in education are good examples of areas of focus. Set a first-year target of 1,000 two-way student-months through the Kinmen-Xiamen corridor, using transparent selection and public course materials. Link each small program to tangible results: a certification, an open-source tool, or a small dataset. In year two, expand to degree-level cotutelle trials in fields where both sides already excel. Keep discussions of defense and sovereignty off the table; let outcomes, not symbolism, drive the agenda.

Why now? Beijing has already shown, through its relationships with Australia and parts of Southeast Asia, that generosity can break cycles of tension and create space for interests. It has a ready policy framework in the Fujian integration blueprint, which can be reshaped into a rules-first approach focused on education with Taiwan. Taipei can utilize education diplomacy to define the terms of contact instead of yielding control, maintaining autonomy while reaping the rewards of engagement. When choosing between risk with no learning and learning with safeguards, responsible leaders should opt for the latter.

In conclusion, the 84.4 percent figure does not negate engagement; it serves as a guide for it. It indicates that political solutions framed as absorption will not succeed. It also shows that people are open to safety, dignity, and opportunities. Education diplomacy offers a practical path that meets these needs. Beijing can continue to assert its strength with military displays and press releases, or it can demonstrate confidence by opening up classrooms. Taipei can keep viewing contact as a risk to minimize, or it can design contact to spread skills and reduce anxiety. The region has shown that generosity can stimulate markets and repair relationships. Applying the same strategy cleanly and consistently to Taiwan may not resolve the final status. But it will foster the only currency that matters in a democracy: trust. Start with visas, credits, and scholarships. Measure outcomes. Expand what works. The wall of public opinion will not crumble overnight. Still, it will shift one group at a time—if classrooms replace crises as the central focus of cross-strait relations.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

ABC News (Australia). (2024, March 28). China’s government officially abolishes heavy tariffs on Australian wine.

AmCham China. (2024, November). One Year into the “50,000 Students” Initiative.

Beijing Municipal Government. (2024, March 1). Visa-Free Travel Between China and Thailand Starts.

Chicago Council on Global Affairs. (2024, December 2). Americans and Taiwanese Favor the Status Quo.

China Briefing. (2023, August 4). China Removes Barley Tariffs on Australia.

Fujian Provincial Government / China Daily. (2025, June 18). Fujian recognized as beacon for cross-Strait integration.

Human Rights Watch. (2025, February 17). China: Right to Leave Country Further Restricted.

ICEF Monitor. (2025, April 2). Taiwan is close to reaching its pre-pandemic benchmark for international enrolment.

Lowy Institute. (2025, May 12). China’s “friendly neighbourhood diplomacy” has consequences for Australia.

Ministry of Finance (Taiwan). (2025, January 16 & February 25). 2024 External Trade Report / Statistical Bulletin: Export share to Mainland China & Hong Kong at 31.7%.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (PRC). (2025, October 10). Spokesperson’s Remarks (Regular Press Conference).

Reuters. (2024, March 28–April 1). China lifts tariffs on Australian wine. Reuters. (2025, April 22). China ramps up business charm offensive toward Taiwan alongside political pressure.

State Council of the PRC (Xinhua). (2025, April 15). Neighborhood diplomacy takes center stage as Xi begins visit to Southeast Asia.

Study in Taiwan (Taiwan MOE). (2025, Feb.). Key Numbers: International Students 2024/25 (Mainland China ~3,489).

Taipei Times / CNA. (2025, Apr. 25–26). Huge majority in Taiwan reject “one country, two systems” (84.4%).

Taiwan Ministry of Culture and Tourism Administration (Tourism Bureau). (2024). Visitor Statistical Analysis (Mainland share, 2024).

Wine Australia / Australian Government DFAT. (2024, March 28–Apr.). Removal of duties on Australian wine and WTO notification.

Xinhua / State Council Information Office; CPC Central Committee & State Council. (2023, Sept. 12–28). Fujian Demonstration Zone for Cross-Strait Integrated Development.

AP News. (2024, June 27). Taiwan warns against travel to China after legal threats.

AP News. (2025, October 10). Taiwan’s president pledges to build air defense system.