Schooling for the Era of AI Video Actors

Published

Modified

AI video actors are moving from demo to real production and education They cut costs for routine content but raise rights, ethics, and disclosure duties Schools must teach rights-aware workflows, when to use AI actors, and where only humans should lead

One number shows how quickly things are changing: OpenAI’s new Sora app reached one million downloads in less than five days. This is the fastest launch for a consumer AI video tool so far. It provides professional-quality generative video to anyone with a phone. Users can also “cast” themselves into scenes with a cameo feature and share the results online. The message is clear. As creation becomes as easy as a tap, production models change, and the demand for some types of on-screen work shifts. AI video actors are not just science fiction or a niche market. They are a reality that impacts distribution, raises legal questions, sees market adoption, and has simultaneous implications for classrooms. Education systems that still view this as a future issue will struggle to prepare students for the jobs—and the challenges—emerging around synthetic performance.

AI video actors are now a production reality

Studios and streaming services have begun testing generative video in real productions. Netflix revealed its first use of generative AI effects in El Eternauta this summer, presenting it as a way to support creators, not just save money. At the same time, the public debut of a completely synthetic “actress,” Tilly Norwood, prompted backlash from the industry and a response from unions. The common theme is evident: AI video actors are becoming part of the workflow and are already a topic of public debate. A central talent agency has noted that tools like Sora present new risks to creator rights. Schools that train performers, editors, and producers must treat these facts as a starting point.

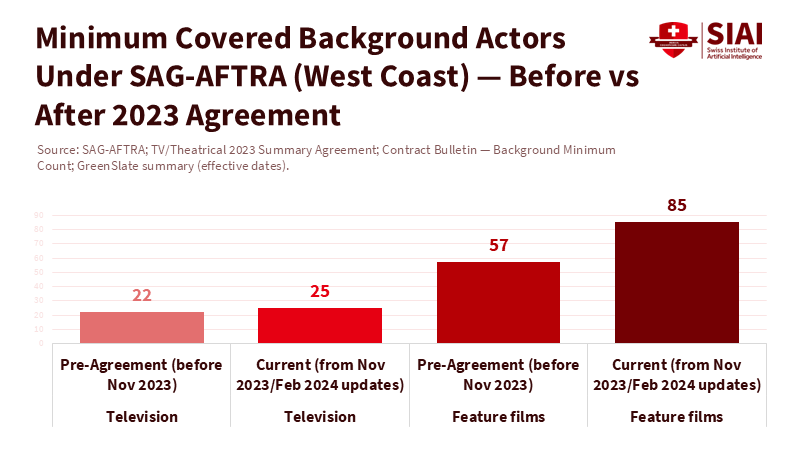

The rules are changing, too. The 2023 SAG-AFTRA TV/Theatrical agreement recognizes two essential categories for classrooms and on-set work: “digital replicas” of real performers and “synthetic performers” that look human but are not based on any specific person. The contract requires notice, consent, and payment when creating and reusing digital replicas, and it establishes limits on the number of human background actors that must be hired before using synthetic substitutes. Educators should teach these definitions and rights alongside acting technique or VFX. This knowledge is essential for employability.

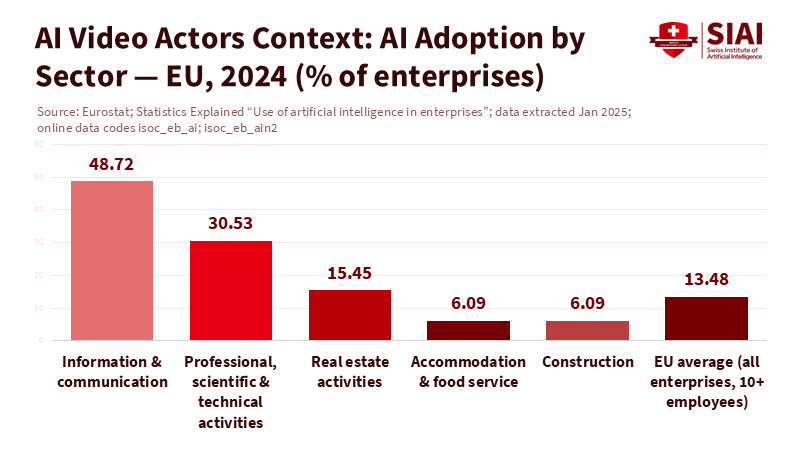

Another baseline is capability. OpenAI’s latest model focuses on more physical realism, synchronized dialogue, and tighter control. These features, combined with a popular social app, reduce the time and effort previously needed for decent composites and crowd scenes. The initial impact will be felt in low-budget advertising, industrial training, and background performance—exactly where new graduates often start. AI video actors make these processes smoother, so curricula must shift toward teaching skills that match this trend: directing generative models, navigating the prompt-to-performance workflow, understanding rights-aware postproduction, and making editorial decisions about what should not be automated.

What AI video actors mean for learning and work

The evidence shows that the education landscape has moved from hype to tangible signals. A recent study in Nature found that an AI tutor led to greater learning gains than a typical in-class active-learning scenario while using less time. Similarly, research comparing human-made and AI-generated teaching videos demonstrates that synthetic instruction can deliver similar or even better learning outcomes under specific design conditions. Another peer-reviewed study indicated higher retention with AI-generated instructional videos, although the ability to transfer knowledge remained similar to human-recorded material. The key takeaway is not that AI will replace teachers. AI video actors can effectively deliver instruction when the teaching methods and transparency are solid.

This shift matters for training in creative industries. If synthetic presenters can handle standard modules—like safety briefings, software onboarding, and compliance training—then human talent can focus on high-touch coaching, feedback, and narrative development. This reflects the current challenges faced by film and media programs. They need to prepare students to lead hybrid teams where AI video actors perform repetitive takes, while humans handle scenes requiring timing, improvisation, and empathy. The learning aim for students should be about judgment, not just skills: knowing when to cast a synthetic stand-in, how to direct it, and when a human presence is necessary because the audience will notice and care.

The overall school system also needs a proactive approach. UNESCO’s guidelines advocate for a human-centered approach and call for strong policies before tools become widespread, while OECD reports indicate that deepfakes are already negatively affecting students and teachers. If AI video actors become commonplace in entertainment and education, then media and AI literacy must be integrated into the curriculum. Students should practice detection skills while also learning about ethics: consent, context, and the differences between parody, instruction, and deception. These topics are not just theoretical discussions; they are practical decisions in classrooms, campus studios, and corporate training settings.

Building responsible pipelines for AI video actors

Education and policy need a common framework: transparency, consent, compensation, and control. The union contract establishes this framework for productions, and schools can adopt similar practices. Require performers to sign clear likeness licenses during student shoots. Log prompts and assets for every synthetic clip. Teach revenue sharing when likeness or voice models add value to a project. This is not merely an ethical matter; it is a standard practice that transitions smoothly into the industry. It also addresses the concerns raised by major Hollywood agencies about creator rights in the age of Sora.

Institutions should also create “do-not-clone” registries based on app platform norms. OpenAI has introduced features allowing rights holders to restrict use and manage how their likeness appears on the platform. Schools can adopt similar measures with campus-level registries and honor codes. Simultaneously, educators should teach technical controls for safer synthesis: watermarking, content credentials, and verification workflows that track media from creation to final product. In the short term, these steps will be more effective in reducing harm than waiting for slow-moving regulations, while providing students with practical experience in compliance.

K-12 schools and universities should integrate this with media literacy goals. Use synthetic clips to conduct live evaluations: What giveaways hint at AI video actors? What disclosures seem adequate? At what point does it become unethical? UNESCO and OECD frameworks can support such initiatives. The goal is not to turn everyone into filmmakers but to equip the next generation of citizens and professionals to discern intent and consent when any face on a screen might be a model, a remix, or a real person.

Where humans still lead—and how schools should teach it

There is no substantial evidence that AI video actors can fully replace human performers in complex drama. In fact, learners often find human feedback more beneficial than AI feedback when it comes to nuances and relationships. Several reviews emphasize that good design, not novelty, is what drives impact. This should inform the curriculum. Programs should restrict the use of synthetic tools to areas where they help with repetition and scale, while focusing on live direction, teamwork, and the ethics of representation in high-stakes storytelling. We need to maintain the emphasis on human strengths: meaning, memory, and trust.

Film and media schools can implement these changes within a year. First, introduce a “Synthetic Performance” series that combines acting classes with generative video labs. Students will learn to co-direct AI video actors, set prompts for pacing and eye lines, and blend scenes with human actors. Second, require a rights and safety practicum covering likeness licensing, storage, watermarking, and on-set transparency. Third, update capstone projects to include one that demonstrates restraint: a scenario where the team opts not to use AI because a human moment carries greater weight. Finally, invite unions, studios, and AI companies to participate in critique days so that graduates can enter the market familiar with its changing norms. This approach keeps programs focused on artistry while ensuring industry relevance.

The million-download week was not just a fluke. It marked the beginning of a significant shift. AI video actors will not eliminate the craft of acting or the role of teachers. However, they will streamline many types of production and learning, potentially changing jobs, finances, and practices unless schools take proactive steps. The correct response is not to resist or yield. Instead, it's to innovate. Educators can create courses that provide students with necessary control tools—rights-aware workflows, prompt-to-performance direction, and clear standards for disclosure. Administrators can develop policies that reflect union protections and platform regulations. Policymakers can encourage trustworthy media, not just punishments for misuse. If we do this, we can teach the next generation to collaborate with AI video actors where appropriate while recognizing when a human touch is essential. The tools are here. We should respond with thoughtful judgment.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Authors Guild. (2024). SAG-AFTRA agreement establishes important AI safeguards.

Deadline. (2023). Full SAG-AFTRA deal summary released: Read it here.

Guardian. (2025, Jul. 18). Netflix uses generative AI in one of its shows for first time.

Guardian. (2025, Oct. 1). Tilly Norwood: how scared should we be of the viral AI ‘actor’?

Hollywood Reporter. (2024, Apr. 10). How SAG-AFTRA’s AI road map works in practice.

Hollywood Reporter. (2025, Sep. 29). Creator of AI actress Tilly Norwood responds to backlash.

Loeb & Loeb. (2023). Artificial intelligence terms of SAG-AFTRA TV/Theatrical contract (summary).

Nature (Scientific Reports). (2025). AI tutoring outperforms in-class active learning.

OpenAI. (2024, Dec. 9). Sora is here.

OpenAI. (2025, Sep. 30). Sora 2 is here.

OpenAI Help Center. (2025, Oct. 2). Getting started with the Sora app.

Perkins Coie. (2024). Generative AI in movies and TV: How the 2023 SAG-AFTRA and WGA contracts address generative AI.

Reuters. (2025, Oct. 1). OpenAI launches new AI video app spun from copyrighted content.

Reuters. (2025, Oct. 9). CAA says OpenAI’s Sora poses risk to creators’ rights.

Reuters. (2025, Oct. 2). Hollywood performers union condemns AI-generated “actress”.

SAG-AFTRA. (2023). TV/Theatrical 2023 summary agreement (AI and digital replicas).

Scientific American. (2025, Oct.). OpenAI’s new Sora app lets users generate AI videos—and star in them.

UNESCO. (2023, updated 2025). Guidance for generative AI in education and research.

UNESCO. (2025, Oct. 1). Deepfakes and the crisis of knowing.

Verge, The. (2025, Oct.). Sora hits one million downloads in less than five days.

Wiley (BJET). (2024). Assessing student perceptions and use of instructor versus AI feedback.

MDPI Education. (2025). From recorded to AI-generated instructional videos: Effects on retention and transfer.

Computers & Education. (2025). Comparing human-made and AI-generated teaching videos.