European scholar networks: how distributed prestige beats brand power in higher education

Input

Modified

European scholar networks lift collaboration and raise median quality U.S. brand hierarchies concentrate prestige, limiting diffusion and equity Fund bridges, reform assessment, and measure diffusion to scale excellence

Europe's strength lies not in a few well-known campuses, but in a network. In 2022, 56% of all EU scientific papers were co-written with international partners, far exceeding the rate in the United States, which was only 40%. This gap reveals how European scholar networks connect different systems into a unified research engine, while a brand-focused model concentrates advantage in a few elite institutions. This isn't just a cultural preference; it's a straightforward way of producing knowledge. More cross-border co-authorship leads to more sharing and resilience within the system. This is also evident in funding. In 2024, the EU increased the portion of its central R&I budget allocated to "widening" countries to 14%, nearly doubling their share from previous frameworks. In the same year, ERC Starting Grants supported 494 early-career researchers across 24 countries. Networks, not brands, are driving progress.

European scholar networks redefine what prestige means

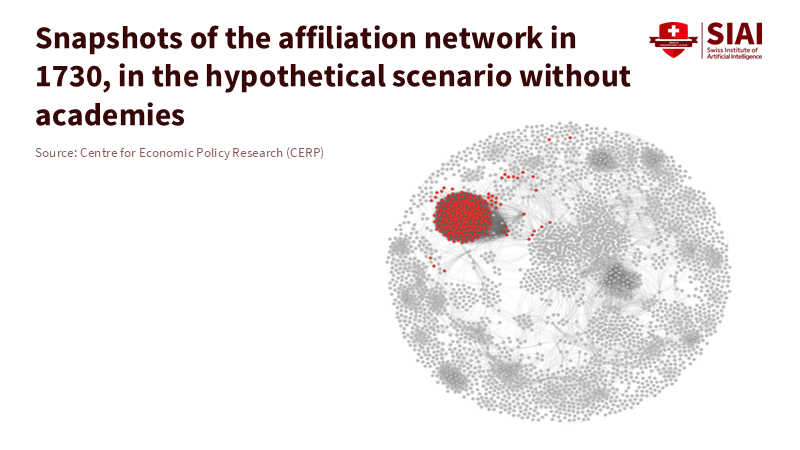

The core idea is straightforward. A network-first system values contribution and connectivity more than campus logos. Europe intentionally created this system through the European Research Area, cross-border funding rules, and open hiring processes. The results are precise in the publication data. The EU ranks second globally in research output and promotes collaboration that rivals or exceeds other major science-producing countries. The United States remains powerful, but its structure differs significantly. Much of its faculty job market follows a prestige hierarchy. Studies of U.S. hiring networks reveal significant disparities in faculty production and placement. One analysis shows that about 80% of tenure-track faculty come from just 20% of universities, with one in eight trained by five schools. That illustrates brand power at work. While it's efficient for maintaining status, it can hinder knowledge diffusion.

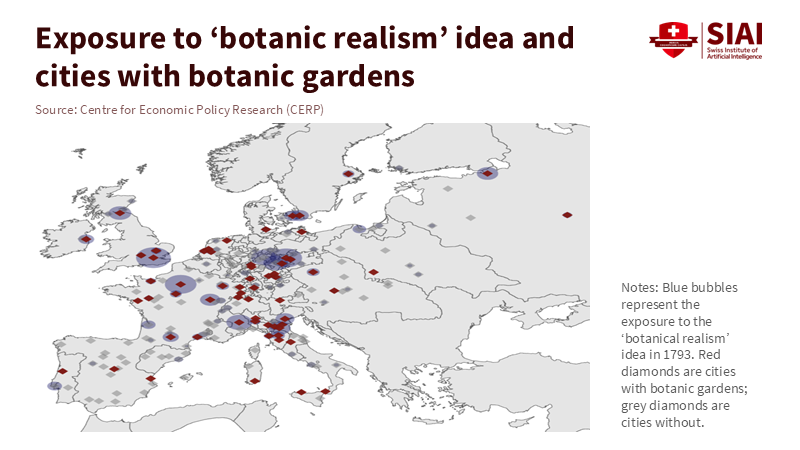

In a networked model, "where you teach" is less important than "what you produce and with whom." In Europe, local hierarchies exist, but the cross-country network softens their impact. The European scholar networks, including ERC teams, Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowships, and Horizon Europe consortia, promote ideas across borders and languages. In 2024, the MSCA Postdoctoral call received 10,360 proposals, and funding is expected for around 1,700 projects—each serving as a connection between institutions. Simultaneously, Europe is increasing the number of active researchers: from 2013 to 2023, EU researcher numbers rose by approximately 45% (FTE). The system is growing without requiring each career to navigate several gates in Cambridge or Palo Alto.

How networks raise the median

The main benefit of European scholar networks is that they elevate the overall standard of education. Collaboration is not just a slogan; it predicts impact. International co-publications receive more citations than domestic ones, and Europe has developed a system to generate them. In 2022, 56% of EU papers were international co-publications, with about 59% of those collaborations occurring within the EU, demonstrating a robust internal market for ideas. Europe also leads in openness: around 80% of EU peer-reviewed papers were open access in 2020, allowing quicker and wider sharing of knowledge. This broad reach is also evident at the institutional level. The EU's 2024 performance report highlights a more even quality distribution across various mid-tier institutions, rather than dominance by a few large ones. This is precisely what you'd expect from a network designed to spread opportunity rather than concentrate it.

Funding patterns support this narrative. The widening agenda increased its budget share to 14% under Horizon Europe, rising from 8% previously. ERC awards also show a wide geographic distribution. The 2024 Starting Grants supported 494 principal investigators across 24 countries. The 2025 Starting Grants again funded over 12% of nearly 4,000 proposals, maintaining women's participation in the low-40s, indicating a healthy supply and broad demand. Advanced Grants in 2025 funded new projects across 23 EU and associated countries, including the UK. Europe is not just giving out small awards; it is establishing labs throughout the region.

Moreover, the network is expanding and becoming more accessible. The EU's reform of research assessment (CoARA) has shifted hundreds of universities and funders away from narrow journal metrics and toward recognition based on contributions. By August 2024, over 700 organizations had signed the agreement. Additionally, associated countries contributed over €4 billion (2021–2024) to Horizon Europe, expanding the network beyond the EU-27. Policy is effectively investing in reducing the benefits of pure branding while increasing the rewards from cross-border collaboration.

Policy design for the next decade

What should governments and universities do to achieve more of the European effect? First, fund networks instead of focusing on logos. Aim for multi-PI grants that require absolute mobility for people and data across borders and sectors. The ERC/MSCA model works well by investing in people and allowing them to choose their partners. The 2024 MSCA call shows significant demand, with 10,360 fellowship proposals for approximately 1,700 positions. Prioritize these connections in expanding regions first. Use Horizon-style teaming and ERA Fellowships to integrate rising universities into top-tier networks within two grant cycles.

Second, measure diffusion, not just high points. Every science ministry should publish an annual "Network Equity" audit: the percentage of national output from cross-border teams, the number of ERC-class awards given outside the top decile of institutions, and the rate at which co-authorship connections spread from established researchers to newcomers. The EU currently tracks international co-publication and shows that it predicts higher citation impact. Allocate budgets based on these indicators. Suppose a university increases its international co-authorship share by 10 percentage points in three years, especially with partners from widening countries. In that case, it should receive a funding bonus.

Third, reduce risks associated with mobility and co-supervision. Europe's free movement of researchers is an asset that should be made more accessible and efficient. Expand easy visa processes and standard IP templates so that small and medium enterprises and public labs can collaborate without excessive legal hurdles—link doctoral funding to joint degrees and co-supervised theses that require at least one semester abroad. Use micro-credentials to acknowledge training in visiting labs, ensuring supervisors value network building in hiring practices. The goal is to make the European scholar networks evident on CVs in ways that surpass simple brand signals.

Fourth, match assessment with networks. CoARA serves this purpose. Funders should make participation optional yet beneficial by providing access to special network calls, simplified paperwork, and quicker grant cycles for participants. As of 2024, most CoARA members are universities, but the coalition now includes funders and ministries as well. Continue to broaden this base so that assessment reforms cannot be manipulated by merely renaming prestige.

Responding to the critics

Two main criticisms arise. The first suggests that network systems diminish peaks and reduce excellence. The second claims that Europe cannot compete with the U.S. in terms of resources and speed. Both points warrant a clear response. Regarding excellence, Europe's publication impact data are precise: international co-publications consistently receive more citations than the average paper, and Europe produces a significant number of them. This isn't dilution; it's leverage. In terms of resources, the EU's R&D spending still lags behind that of the U.S. (about 2.3% of GDP compared to 3.5% in 2021). Yet, Europe remains second in global output. It is expanding its capabilities, with the researcher workforce increasing by approximately 45% over the past decade. The network model appears resource-efficient, producing more scientific output per euro by making spillovers common rather than uncommon.

A sharper response from the U.S. posits that concentration creates world-class universities that serve as global leaders. This is true. However, concentration has drawbacks. U.S. faculty hiring networks exhibit steep prestige hierarchies. Social mobility into elite leadership positions is dominated by "Ivy-Plus" schools, which significantly increase the chances of landing elite jobs and account for large portions of senators, CEOs, and justices. This system has its own efficiencies, expediting coordination through shared backgrounds. It also creates difficult-to-break barriers that can influence which ideas receive funding and education. Europe's distributed model sacrifices some peak performance for a stronger overall system. In an age where scientific challenges are complex and cross-sectoral, this trade-off makes sense.

A final concern is fragmentation within Europe. The Commission's analysis has pointed out collaboration gaps in patents and uneven integration compared to the U.S. This is real, but it is also improving. The budget share for widening initiatives has risen to 14%, associated countries have invested €4 billion into the program, and ERC awards are being distributed across multiple host countries each year. The policy goal should be clear: reduce the number of isolated institutions and increase connections. Encourage patent co-filing and co-ownership across borders by adapting ERC's people-first approach for technology transfer and intellectual property. Continually reform assessment so that collaborative efforts are valued more than vanity metrics.

The most crucial figure in this discussion is simple: 56% of EU papers are written with international partners, compared to 40% in the U.S. This statistic highlights Europe's regular practice of creating scholar networks that facilitate the movement of talent, ideas, and recognition across borders. The outcome is a system that raises the standard of median institutions while also supporting high performers. This approach opens up opportunities, reduces reliance on branding, and turns public investment into knowledge that flows freely. The next decade should reinforce this strategy. Fund connections. Reward teams that welcome new universities: audit diffusion, not just peaks. Continue to reform assessment, so personal contributions and network value outweigh campus reputations. If Europe pursues these goals, it will not only remain competitive but also provide a model for systems seeking excellence and equity without the limitations imposed by brand power. The network will surpass the logo because it scales.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Chetty, R., et al. (2023). Diversifying Society's Leaders? The Determinants and Causal Effects of Admission to Highly Selective Colleges. NBER Working Paper 31492. (See also Opportunity Insights non-technical summary.)

European Commission (2024). Science, Research and Innovation Performance of the EU 2024 (Chapter 3: Scientific knowledge production).

European Commission (2024). Communication on Widening Participation and Spreading Excellence. (Budget share for widening under Horizon Europe.)

European Commission (2025). Horizon Europe association state of play 2021–2024 (Associated countries' €4 billion contribution).

European Research Council (2024). ERC Starting Grants Results 2024 (494 grantees across 24 countries).

European Research Council (2025). ERC Starting Grants Results 2025 (acceptance rate and gender shares).

European Research Council (2025). Advanced Grants Results 2025.

Eurostat (2025). R&D personnel — Statistics Explained (researcher headcount growth 2013–2023).

Larremore Lab et al. (2022). Quantifying hierarchy and dynamics in U.S. faculty hiring and retention. Nature Human Behaviour (and data portal).

Inside Higher Ed (2022). New study finds 80% of faculty trained at 20% of institutions.

National Science Board / NSF (2023). International Collaboration and Citations.

Science|Business (2025). Commission analysis lays bare fragmentation of European innovation.

CoARA / ERA Monitoring (2025). ERA Monitoring 2024,

MSCA (2024). Postdoctoral Fellowships 2024 — call statistics (10,360 proposals; ~1,700 funded).