Let’s Stop Pretending: The EU Needs an EU Federal Tax or It Should Drop the Federal Act

Input

Modified

The EU can’t act like a federation with a 1–1.5% GNI budget A modest EU federal tax with conditional budgeting would fund shared projects and defuse North–South distributional fights Pair ETS/CBAM/CORE revenues with strict caps and transparency to build consent and repay common debt

The European Union’s central budget is small. In 2024, U.S. federal spending was 23.4% of GDP. In contrast, Europe’s long-term budget for 2021 to 2027 is just 1.14% of EU GNI. Even with the recovery fund, the combined total averages about 1.54% during that period. The significant difference is noticeable. A “federal” center that spends one-twentieth of what its counterpart does cannot be expected to stabilize, insure, or strategically guide a €16-trillion economy. This gap explains the chaos during every crisis, from pandemics to wars: Europe talks big but acts small. The outcome is a cycle of temporary fixes, national vetoes, and disputes over distribution that leave everyone unhappy. If we want a center that can truly make decisions—and face the consequences—the EU needs an EU federal tax. Without it, “federal” ambitions will remain just for show, while member states continue to control the narrative.

EU Federal Tax: The Missing Piece

The issue is not about ideology; it is about numbers. Today’s EU “own resources” mainly come from national contributions. In 2025, around 65% came from GNI-based transfers, 16% from VAT, and a small portion from genuinely independent sources like customs and the plastics levy. The center’s budget acts mainly as a clearinghouse for funds raised by the states. This is why each attempt to increase spending leads to arguments over “who pays” and “who benefits.” The setup is not made to foster agreement on discretionary fiscal policy; it aims to maintain national control. The center can coordinate, but it cannot lead.

The pandemic-era exception, NextGenerationEU, showed both the potential and the limits. Europe managed to raise about €800 billion in the markets and recycle that money into national plans. This helped dampen the impact and provided time. However, it was designed to be temporary and financed through debt, which still requires a steady revenue base to be repaid over decades. We see a similar pattern with the Ukraine Facility, a €50-billion, multi-year program that needed another last-minute deal. Each initiative is helpful in the short term, but they all follow the same pattern of negotiation. A sustainable federal-style capacity requires a federal-style revenue source. This means a modest, rule-based EU federal tax with clear limits, independent management, and oversight from Parliament.

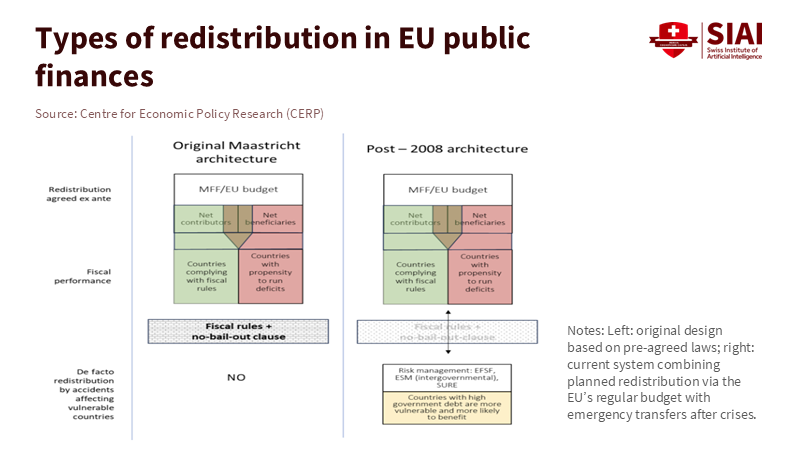

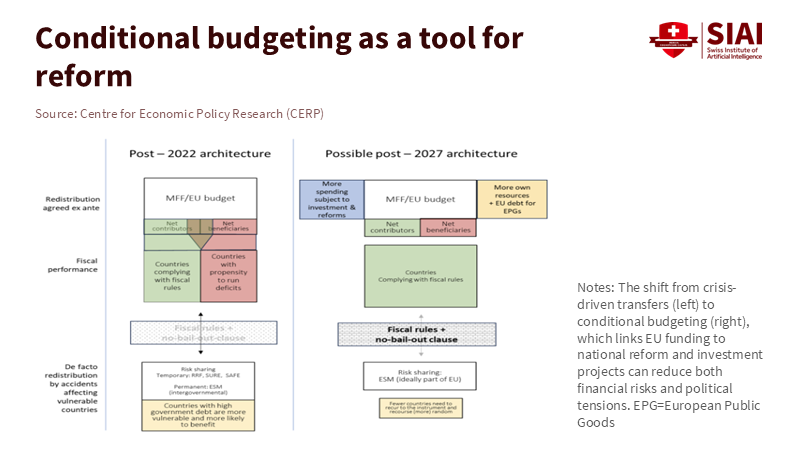

Conditional Budgeting Can Align Incentives

The biggest political issue is not technical design; it is trust. Countries worry that centralized spending will become long-term transfers, and they have good reason for this concern. A credible solution is conditional budgeting: tie any EU-level spending supported by an EU federal tax to clear performance rules and time-sensitive goals. Recent studies suggest that linking spending to measurable targets—such as public goods provision, progress in decarbonization, and supply chain resilience—can transform redistribution from an open checkbook into a contract. This approach prevents the shift into everlasting entitlement while maintaining risk-sharing. It is the only way to bring together both net contributors and net recipients in a diverse Union.

The logic applies to current disputes. Imagine the center funding a German manufacturing revival after an energy crisis. Italian automakers would question why Berlin receives the boost when Turin faces similar challenges. Consider expanding solar energy in the Mediterranean to take advantage of sunlight. Northern governments would want to know what benefits their workers and companies would get in return. Conditional budgeting addresses these concerns by linking EU funds to EU goals—like reducing emissions, integrating energy grids, building cross-border training programs, and establishing procurement rules that distribute contracts throughout the single market. This shifts the focus of negotiation from “who” to “what”: if a project meets agreed metrics, it qualifies for funding. If it doesn’t, it waits. This is how federations gain consent while accommodating diversity. The alternative is ongoing haggling that jeopardizes strategic projects whenever circumstances change.

What a Small, Rules-Based EU Federal Tax Could Fund

Scale is important. The EU’s long-term budget allocates about 30% to cohesion and a similar amount to agriculture. Those categories are not going away. However, they cannot alone fund new public goods such as grid connections, defense mobility, dual-use research and development, and industrial decarbonization. A modest EU federal tax of around 0.5% to 1.0% of EU GNI could double or nearly triple the center’s discretionary budget compared to the 2021 to 2027 baseline. While this is still far less than U.S. federal spending, it would provide enough room to support multi-year programs without constant brinkmanship. Adding a rule that any temporary crisis funding expires unless reauthorized by Parliament and Council would help control fiscal growth.

Europe has already taken steps toward new own resources. The Commission has proposed revenue from the Emissions Trading System (ETS) and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which could yield about €9.6 billion and €1.4 billion annually, respectively. While these figures help, they do not create a federal-scale capacity. A broader solution could be CORE, the proposed “Corporate Resource for Europe.” Under CORE, huge companies benefiting most from the single market would contribute a modest, graduated lump sum, capped per company, generating estimated revenues of about €6.8 billion per year, according to the Commission. While some criticize this idea, it points in the right direction: link revenue to benefits at the EU level and keep rates low, bases broad, and administration centralized. Combining ETS, CBAM, and CORE under a conditional, time-limited spending rule improves the political situation.

A Credible Path to Consent and Control

Two objections come up frequently. First, some suggest that an EU federal tax threatens sovereignty. In reality, sovereignty diminishes when the center must improvise in every crisis. The Ukraine Facility, for instance, required significant political effort to secure €50 billion in multi-year support. Proposals to utilize frozen Russian assets and create guarantees outside national budgets reinforce the argument: when revenue is uncertain, the need for legal creativity increases, and trust decreases. A small, well-defined EU tax with strict limits and democratic oversight is less intrusive than ongoing, ad-hoc agreements. It reduces the chances of emergency shortcuts while allowing for national fiscal space for domestic priorities.

Second, critics contend that a federal tax would create permanent winners and losers. While this risk exists, it can be mitigated with a well-designed spending rule. Conditional budgeting should ensure that programs fund EU public goods with cross-border benefits, establish clear geographic distribution guidelines, and promptly publish contract winners. Suppose solar projects are concentrated in the south. In that case, grid upgrades and training contracts can be allocated to the north to balance benefits. If a German, French, or Italian industry cluster receives support for a transition, supplier development and apprenticeship programs can be extended across European value chains. In simple terms, we replace opaque negotiations with transparent formulas that distribute opportunities.

The timing is right. Germany’s industrial slowdown has highlighted the vulnerability of Europe’s manufacturing base. Automotive production has fluctuated dramatically, with sharp declines recorded throughout 2024 and again in mid-2025. Countries relying on this value chain—such as Italy, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia—suffer when demand weakens or costs rise. The policy choice is clear: either fragmented national aid packages try to address issues, or the center supports common transitions with conditions that safeguard the single market. If we opt for the latter, a dedicated EU federal tax will shift from being a theory to a necessity.

The Prize and the Guardrails

The design needs to be purposefully simple. Begin with a low rate and a narrow base. Restrict the EU federal tax to a few distinctly European bases—such as carbon, concentrated market profits, and the largest beneficiaries of the single market—so that national tax authorities are not heavily impacted. Set an annual cap as a percentage of GNI. Grant the European Parliament binding authority over usage and public disclosure. Ensure that any multi-year program includes evaluations tied to funding renewals. Finally, maintain the “automaticity” that has proven effective: when a crisis occurs, pre-existing agreements should release EU funds to support cross-border demand and then wind down.

There is also the issue of scale in relation to debt. NextGenerationEU demonstrated that collective borrowing is both feasible and beneficial, but debt needs a revenue source. ETS, CBAM, and CORE could collectively cover a noticeable portion of repayments. Still, their expected revenue is insufficient to support a strategic agenda by itself. Policymakers should consider these as a foundational layer. Beyond that, a small GNI-linked EU federal tax can fill the gaps and fund programs that meet conditionality requirements. This is not an unlimited mandate; it is a restricted one. It provides the Commission and Parliament with the tools to act while compelling them to demonstrate value to voters each year.

Finally, we must address the political mindset. As long as national roles are viewed as the pinnacle of power, positions at the European level will be seen as detours rather than goals. This perspective undermines the case for central authority and supports the idea that Brussels should only coordinate. The solution is not just about talking; it is about results. If the center can fund projects that provide households and businesses with better connections, improved training, safer digital systems, and lower energy costs, its authority will grow. This is how federations develop: one realized project at a time, funded by clear, shared revenue.

Pay for the Europe We Say We Are

Europe often acts like a federation in crises and a confederation during calm periods. This pattern is not sustainable. The next decade will be tumultuous: decarbonization, defense, artificial intelligence, enlargement, and an accelerating global economy that won't slow down for our discussions. A center that constantly needs to beg for funds during crises and seeks consent for every program cannot lead effectively. The numbers outlined earlier tell the story. The U.S. federal government spends over 20% of GDP, whereas the EU’s central budget represents a fraction of that, with much of it funneled through national budgets. Europe cannot simply adopt another country’s model, but it can aim for coherence. A modest EU federal tax, along with conditional budgeting and strict limits, would allow the Union to operate effectively without becoming a transfer union. It would replace improvisation with rules, leverage the single market for joint projects, and reduce the discord that currently accompanies major decisions. If Europe desires a federal-style outcome, it must accept a federal-style input: a small, visible, democratically managed tax. Pay for the Europe we claim to be, or be truthful about what we are not.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bipartisan Policy Center. (2025). Visualizing CBO’s Budget and Economic Outlook.

CBO (Congressional Budget Office). (2025). The Federal Budget in Fiscal Year 2024: An Infographic and Monthly Budget Review.

CEPR VoxEU. (2025, October 15). Conditional budgeting: Striking a balance in EU economic governance.

Consilium of the European Union. (2025). Financing the EU budget—Own resources.

European Commission. (2025). EU budget 2028–2034: New own resources (ETS, CBAM) — expected revenues.

European Commission. (2025). Recovery plan for Europe (NextGenerationEU).

European Commission. (2025). The Ukraine Facility.

European Parliament Research Service. (2025). Budgetary Outlook for the European Union 2025.

KPMG. (2025, July 16). EC proposal for a system of EU own resources.

LSE EUROPP. (2025, August 28). The Commission’s foray into corporate taxation – a CORE problem for the EU budget?

Reuters. (2025, October 8). German industrial output falls; auto production drops sharply.

Tax Foundation. (2025, July 18). The EU Budget’s CORE Is Rotten.