From Search Engines to Schools: Eigenvector Centrality in Education

Input

Modified

Learning spreads through educator networks Eigenvector centrality pinpoints the hubs to seed first Targeting those hubs speeds recovery systemwide

Seventy percent of 10-year-olds in low- and middle-income countries still cannot read a simple passage with understanding. This number should influence every education policy decision we make. It shows us that time, reach, and sharing knowledge are essential. Money only helps when it quickly moves skills along the paths where teachers influence each other. We see the same lesson in wealthier systems. Between 2018 and 2022, average performance across the OECD dropped by almost 15 points in mathematics and 10 points in reading, marking the steepest decline on record. These losses are widespread, affecting many different schooling models. The pattern reveals challenges in how methods spread within actual school networks. Some teachers are in influential positions, while others are on the edges, hard to reach and easy to overlook. Eigenvector centrality in education highlights this structure. It considers who your neighbors are, not just how many, and turns a static staff list into a map for sharing practices.

Why eigenvector centrality in education changes priorities

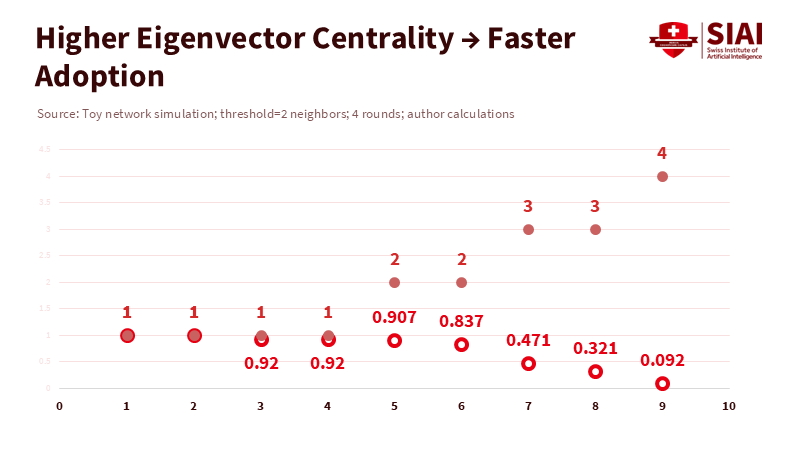

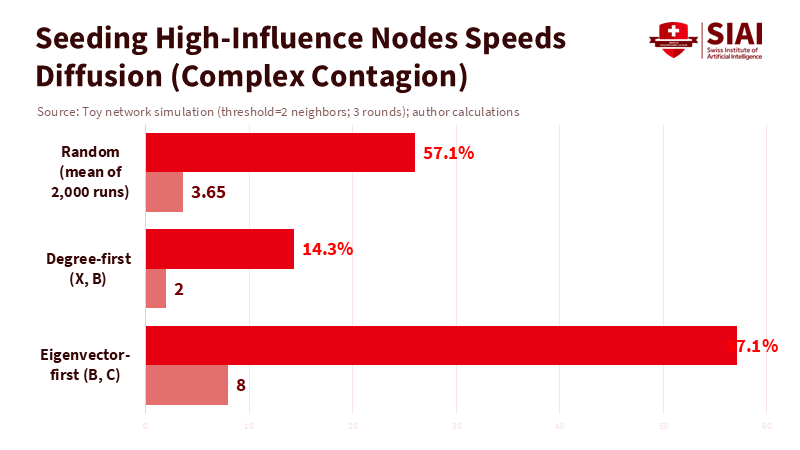

We need a clear rule that directs limited support to the people and places where it will have the most significant impact. Eigenvector centrality provides this rule in a form that leaders can use without needing to be mathematicians. The idea is straightforward. A node is influential if it connects to other influential nodes. In schools, a mentor who is linked to other mentors shares practices faster than one who is mainly connected to isolated teachers. This logic reflects what we already sense in staffrooms and professional development days, where experienced teachers often lead discussions and share best practices. It also scales, as the same principle applies to school-to-school connections across a district. The math behind this idea is simple and aligns with how influence builds in real work. Suppose we initiate change at the center of the network rather than at the edges. In that case, each hour of coaching becomes more effective. If we maintain the links between clusters, each new initiative will progress faster than the last. When the goal is to address learning loss quickly, this leverage is crucial.

How the score is computed:

$$

A\mathbf{x}=\lambda\mathbf{x}

$$

This equation shows that a node's score increases when it connects to other nodes with high scores. We use it to allocate help, not to judge people. In directed networks, such as when curriculum leaders distribute materials, a PageRank-style variant includes a 'random jump' and direction. However, for most reciprocal staff collaboration, the basic eigenvector model is sufficient to guide initial actions. The real test is not how elegant the model is; it's whether the ranking helps a team efficiently share tools and practices across classrooms. The goal here is to take a clear, structural view of where influence lies, then direct limited time and funds to those key positions first.

A centrality-first approach is vital due to the pressing need. PISA 2022 indicates an unprecedented decline in performance across OECD systems. On average, math scores dropped nearly 15 points, and reading scores fell by 10 points since 2018. The shock is significant, but the deeper risk is stagnation. If we try to recover through generic rollouts, we will waste time. Meanwhile, the world faces a severe teacher shortage. By 2030, systems will need about 44 million additional teachers to achieve universal primary and secondary education. This reality makes leveraging diffusion essential. We cannot simply hire our way out of this problem. We must also ensure each hour of expert practice extends as far as possible. Eigenvector centrality in education achieves this by identifying where influence builds and by highlighting the bridges we need to create.

What the recent evidence shows—and how to interpret it

The strongest reason to trust a network perspective is that it explains fundamental differences in outcomes. Studies in 2024–2025 show that centrality measures related to "who influences whom"—including eigenvector centrality—predict achievement better than just counting activities or connections. In one peer collaboration study, higher eigenvector centrality identified students who acted as sources of information; this measure correlated with achievement even after adjusting for other traits. Reviews of online and hybrid courses support this finding. Learners connected with central peers adopt tools more quickly, seek help sooner, and achieve compounded gains over time. Teacher collaboration work in schools shows a similar trend: practices introduced by central staff spread to other classrooms faster than those initiated at the edges. These findings are not mystical. They reflect exposure, timely feedback, and social proof that flow along actual connections. Centrality makes these ties visible and provides leaders with a systematic way to leverage them.

However, using centrality effectively also requires clear boundaries. First, centrality is about structure, not morality. A fantastic teacher may be marginal if scheduling isolates their subject team or if travel times hinder cross-school collaboration. Use the map as a routing guide, not a ranking system. Second, match the measure to the situation. When influence is truly directional—for example, with curriculum teams distributing materials—a PageRank style with a damping factor is more appropriate. When collaboration is mutual, such as co-planning, mentoring, and lesson study, the classic eigenvector centrality is the proper tool. Third, validate the ranking against essential outcomes. If the model suggests certain staff or schools should be early adopters, check whether screening tools, item banks, or formative practices appear there first. If the predictions and actual uptake differ, look for missing connections instead of blaming individuals. Often, the network is inaccurately measured because a key forum, chat channel, or cross-school meeting wasn't included in the data.

Context also plays a role in equity. Central hubs can widen gaps if they primarily share resources within strong clusters. This represents a design issue, not a reason to discard the approach. Use the map to fund bridges that connect various clusters. Align or stagger schedules so different subjects can meet. Rotate lesson-study leaders to connect weaker and stronger teams. Provide travel funding for rural departments to meet in person once a term. Establish light but ongoing cross-school networks that maintain connections to the core. When the next initiative is introduced, these links will support its success. Over time, the network retains the lessons learned. Improvements to structure deliver lasting benefits because each new tool starts from a stronger foundation.

All of this goes beyond mere technique. It transforms a widespread crisis into manageable work. Look at the initial numbers again. Nearly 70 percent of 10-year-olds in poorer countries cannot read a simple text. OECD systems experienced record declines in math and reading between 2018 and 2022. The teacher gap is significant. This combination can lead to hopelessness if we think about the parts rather than the connections. A centrality-first policy breaks the problem into manageable steps. Map the connections. Seed the core. Support the bridges. Track the spread. Repeat. None of these steps requires a national overhaul of the curriculum. Each action builds up if taken with intention.

A practical playbook for eigenvector centrality in education

Start with a clear goal: spread reliable practices faster than confusion spreads. Begin small if necessary. Most systems already have enough data to create an applicable network without new software. Timetables show co-teaching. Professional development rosters reveal who collaborates. Mentoring records indicate who supports whom, while platform logs track who shares resources and how often they are reused. Combine two or three of these data points to create a straightforward staff collaboration graph at the school and cluster levels. Calculate eigenvector centrality in education using a standard tool. Share the results with leaders as maps, not scoreboards. The objective is to provide direct support. Use individual scores sparingly and only within small planning teams. When trust is limited, aggregate data to the team level and allow heads to identify early adopters based on visible patterns.

Next, seed the core. Distribute early versions of screeners, rubrics, and lesson exemplars to teachers and schools located near the center of the map. Give them time to adjust, brief coaching, and two short check-ins. Keep the requests focused. The aim is to establish a working practice within a few weeks, rather than conducting an extended pilot. Meanwhile, support the bridges. Create a standing cross-school forum for each subject with protected time. Align professional development days across feeder schools so teams can meet. Fund travel for rural departments to connect in person once a term. These may not sound exciting, but they fix the essential workings. When these connections improve, every new initiative encounters less resistance.

Track the spread of practices, not just the delivery of materials. Choose two adoption indicators that are easy to record and difficult to manipulate. For example, determine if a class used a new screener by a certain week and if a team pulled items from a shared resource bank into a unit plan. Monitor how long it takes these indicators to reach each department after the first seeds are planted. Chart the spread over several weeks. If adoption stalls at the edges, consult the map for missing connections and address them. If adoption surges across the network, lean into it. Update the list of early adopters for the next term. This process is quick and straightforward. It keeps the work honest without overwhelming teachers with paperwork.

Connect the network plan to staffing. The world will need about 44 million additional teachers by 2030. This demand will challenge budgets and stretch recruitment efforts. In this context, the best way to support student learning is to maximize the impact of each hour of expert practice. A centrality-first approach helps leaders decide where to place coaches, which schools to stabilize as training centers, and which mentors to empower as early champions of change. This doesn't replace investments in pay, professional development, and working conditions. Instead, it complements them by ensuring each additional euro spent on training reaches the most influential parts of the network first. It also minimizes waste by preventing rollouts that lead to dead ends.

Finally, plan for resilience. Networks evolve when people change jobs, schedules fluctuate, or new tools arrive. Incorporate a quarterly update of the map. Use rolling timeframes to ensure no unusual terms dominate the data. When a central teacher moves to a new school, rebuild that connection. If a bridge collapses due to a dormant forum, re-establish the forum and ensure time is allocated for it. Maintain strict privacy and clarity in communication: focus on what is central to facilitate help. It doesn't evaluate. Over time, staff will recognize that being central increases their chances of receiving early tools and extra support, not additional scrutiny. This cultural shift reduces the burden of each new rollout. It also fosters a habit where teams start to consider, before each new initiative, where the network suggests they begin. This instinct marks a system that learns from its own structure.

From crisis to spread

We are confronting record losses in skills and a teacher shortage that will take years to address. We cannot wait for circumstances to improve on their own. We can choose a quicker path by focusing on how practices spread. Eigenvector centrality in education gives us a straightforward method to achieve this. It identifies where a unit of coaching or a better assessment will have the most impact. It also determines which connections to build so that resources do not stagnate. The policy approach is tangible and repeatable. Map the collaboration using the data you already possess. Seed the core initially. Support the bridges. Measure the spread, not just the inputs. Then repeat these actions. The potential for equity is real. When we improve bridges and direct support through the core, classrooms that are difficult to reach will no longer be at the back of the line. The efficiency benefits are also substantial. When influence builds, modest resources can transform entire systems.

Reflect on the initial numbers once more. Learning poverty is still nearly 70 percent for 10-year-olds in poorer countries. OECD systems faced significant drops in math and reading scores between 2018 and 2022. These facts are alarming, but they do not determine our fate. The following two school years can be different if we treat the staff network as essential infrastructure rather than just background noise. This requires resisting the temptation to spread effort too thinly. It means investing in the nodes that drive the network. It means considering bridges as community resources. Most importantly, it means consistently following a simple process: Map. Seed. Support. Measure. Repeat. The calculations are straightforward. What truly matters is developing that habit. If we cultivate it now, recovery will happen sooner, and the benefits will endure when the next challenge arises.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

OECD. (2023, December 5). Decline in educational performance only partly attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic (PISA 2022 press release).

OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education.

Teacher Task Force & UNESCO. (2024). Global Report on Teachers.

World Bank; UNESCO; UNICEF; FCDO; USAID; Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (2022, June 23). 70% of 10-Year-Olds now in learning poverty, unable to read and understand a simple text (press release).

Pesovski, I., et al. (2025). Predicting student achievement through peer network analysis for timely personalization via generative AI. Computers & Education: Artificial Intelligence