Not a Cliff, a Slope: Teaching Through a US-China Power Transition

Input

Modified

China’s rise is gradual, not sudden Power shifts depend on capabilities, satisfaction, and institutions Education must adapt with diversification and resilience

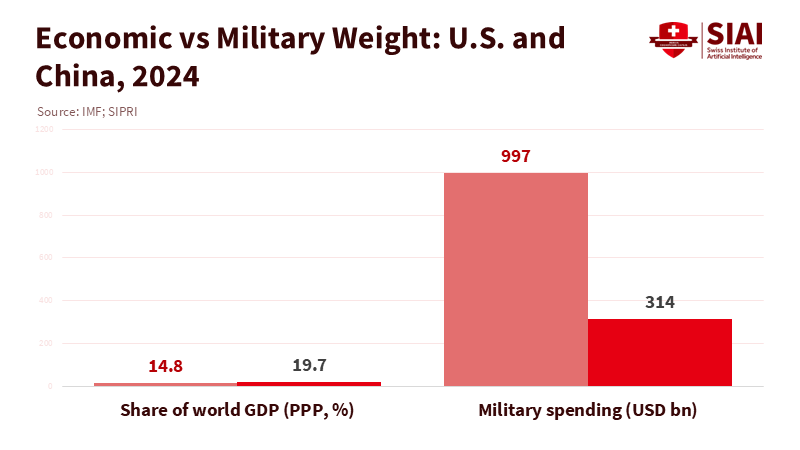

Across the global economy, one pair of numbers frames classroom discussions better than any war metaphor. In 2024, China represented roughly 19.7% of world output in purchasing power terms, while the United States accounted for about 14.8%. Yet, U.S. military spending reached approximately $997 billion, more than three times China's estimated $314 billion, and accounted for 37% of global defense spending. The situation is not a single "handover" moment, but rather a slope with varying gradients. Economic weight is shifting toward Asia, while military strength remains concentrated in America and its alliances. This mismatch is essential for education because knowledge, research funding, student movement, and institutional risk move along this slope rather than falling off a cliff. If we plan curricula and partnerships as if "the moment" will arrive all at once, we will misjudge both timing and policy. We should prepare for a lengthy transition, with different speeds across various areas, and it is through education that we can gain a nuanced understanding and empower ourselves with the necessary knowledge to navigate this transition.

Why Parity Alone Misleads

Power transition theory (PTT) has never been solely about size. Its main idea, from Organski onward, is conditional: the real danger occurs when a rising state nears parity and becomes unhappy with the current situation; if there's no dissatisfaction, parity can exist alongside peace. Dissatisfaction, in this context, refers to a state's perception that the existing international order is unfair or does not sufficiently reflect its growing power. Later refinements clarified that the global system is not purely anarchic but structured by hierarchies, rules, and clubs, which can mitigate or direct conflict. This is what educators need to grasp: two factors—capabilities and satisfaction—interact within institutional settings that can either slow down or smooth out a shift. Practically, GDP shares and military strength tell only part of the story; how each side interprets the benefits of the existing order constitutes the other part. Teaching PTT as a three-dimensional surface—capabilities on one axis, satisfaction on another, and institutional density on a third—helps students understand why transitions tend to be processes rather than events, characterized by prolonged periods of mixed cooperation and competition.

This three-axis perspective also sheds light on Asia's rise. The region's share of global output in PPP terms is around the mid-40s, and trade agreements like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) encompass about 30% of world GDP. These facts suggest growing economic ties and rules, even amidst ongoing strategic rivalry. When we tell students that "history warns of traps," we should add that research indicates nuances: dissatisfaction is not black and white; it can be managed through rules that distribute status and the ability to speak. A wise educator reframes the question from "When is the tipping point?" to "Where are we on the surface, and what drives the system toward cooperation instead of coercion?" This perspective maintains rigorous courses without despair and provides policymakers with a framework to assess risk accurately, rather than inflating it.

The Three Axes of Transition

Let's start with capabilities. In output, China has moved ahead in PPP share, while the U.S. still leads in defense and many cutting-edge technologies. Global military spending reached a record $2.72 trillion in 2024; the U.S. accounted for 37%, with spending 3.2 times that of China. However, the gap in research is narrowing. The NSF's 2025 indicators estimate that in 2022, the U.S. contributed about 30% of global R&D and China about 27%. Newer NSF reports show U.S. R&D rising to roughly $940 billion in 2023, while China's growth rate continues to surpass that. In the AI sector, the 2025 Stanford AI Index reveals U.S. private AI investment exceeding $100 billion and ongoing U.S. leadership in top models, even as Chinese systems close performance gaps. Taken together, these measures indicate a gradual rebalancing: partial economic parity, enduring defense asymmetry, and a research competition with diminishing gaps—precisely the characteristics of a long slope, not a sudden turn. Note: PPP indicates economic weight, SIPRI reports are in constant dollars, and NSF applies PPP adjustments for international R&D comparisons.

Next, let's examine satisfaction, or the perceived "fairness" of the order. It's easy to view tariff barriers, export controls, or visa policies as straightforward measures of discontent, but the research suggests caution. Satisfaction differs among issue areas and audiences; a state might accept maritime rules while opposing tech regulations at the same time. Nevertheless, policy trends in both capitals have shifted toward selective decoupling in sensitive sectors, particularly in semiconductors and AI hardware, alongside updated U.S. controls from 2023 to 2025 and increased allied collaboration. This is a classic sign of contention within the order rather than a break from it; rivalry is being funneled into narrower areas rather than dismantling the structure entirely. For educators, this means that student and research flows remain relatively open. Still, choke points—like chips, computing, and data access—carry higher policy risks than, for example, cultural exchange programs. Teaching PTT using case studies on export controls helps connect the theory to real-world institutional factors.

Finally, examine hierarchy—the density of institutions and alliances that shape choices. Asia's trade and production networks are more robust than a decade ago, and RCEP's scope establishes a rules-based foundation, even as security alliances become sharper. On the trans-Pacific side, NATO's spending has risen to 55% of global totals, with more member countries meeting the two percent-of-GDP target, indicating a lasting capacity to absorb shocks. Simultaneously, Asia remains the world's growth engine, even as the IMF warns of slowing regional growth ahead and risks from escalating tariffs. The teaching point is that hierarchy can cushion transitions: in spaces where rules are well-established, rivalry can be contained, delays can be managed, and universities can plan incrementally rather than reactively. Course modules that combine trade agreements with defense spending trends help students understand how economic and security hierarchies interact to lessen the steepest sections of the slope.

What Education Systems Should Do Now

If the transition is a slope, universities and education ministries should manage exposure by time frame. In the short term, the United States continues to host over 1.1 million international students, with graduate enrollment reaching record highs. Meanwhile, China is opening up to travel and academic exchanges, albeit from lower post-pandemic numbers. Mobility is therefore resilient but not seamless. A wise strategy is to diversify geography, adding new connections while maintaining traditional ones. Dual-degree programs involving the U.S., one Asian hub within the RCEP, and a neutral European partner will lessen the impact of shocks from any single country. For graduate school deans, these numbers do not suggest a retreat from the U.S.; instead, they indicate the need to create credible alternatives and pre-approved credit maps, so students can adjust their plans if visas or sanctions disrupt their progress late in the cycle.

Research policy should follow the three-axis approach. Regarding capabilities, seek complementarity: link U.S. strengths in life sciences and software with Asian strengths in engineering and advanced materials. To enhance satisfaction, create projects that mitigate perceptions of zero-sum outcomes. Open-method repositories, mirrored data enclaves, and jointly governed IP pools can lower political tensions without diminishing ambition. In terms of hierarchy, invest in consortia that are both significant and stable—like standards working groups, data-documentation partnerships, and reproducibility labs. The evidence supports this: China now leads or is nearly on par in several high-quality research metrics. At the same time, U.S.-China co-authorship has decreased from 27% of internationally co-authored U.S. papers in 2019 to 23% in 2023. The goal is to maintain open lines of communication where they are most socially beneficial and least security-sensitive, while developing alternatives where political choke points arise.

The curriculum also needs updating. Teaching PTT through three dimensions allows courses to move beyond catchy slogans. A seminar could start with the IMF's PPP shares and SIPRI's defense data, include NSF's R&D records, and then present a concise reading on dissatisfaction as a spectrum rather than an on-off switch. Students could simulate policy under various slopes: a steeper research-parity slope with flat defense, or a steeper dissatisfaction slope in tech but shallow elsewhere. Method notes can be integrated into assessments: students must specify when they use PPP versus market exchange rates, which years their SIPRI series cover, and how they define "satisfaction." This assessment style—theory combined with choices on measurement—teaches students that conclusions rely on assumptions, and that responsible policy needs to clarify these. It also prepares them to express uncertainty without getting stuck.

Administrators will inquire about budgets. Here, the slope again offers insight. If global military spending is escalating far faster than education funding—a trend evident in many national budgets—then partnerships with philanthropic organizations and industries become crucial to maintain research infrastructure that governments are not prioritizing. The U.S. still leads private AI investment considerably; leveraging those resources for open research pipelines can keep cross-border teams functioning, even as governments pursue different paths. At the same time, establishing small yet solid Asian field sites—in Singapore, Seoul, or Tokyo—anchors presence in regions where growth is steady and regulations are predictable. None of this is radical; it's akin to walking downhill with a firm grip and good shoes.

Critiques will arise from two angles. One perspective argues that the slope metaphor understates risk: power shifts often result in crises, and it's better to "decouple" campus connections. A counter-argument is empirical: Asia's institutions have strengthened, not weakened; cross-regional research capacity has diversified; and the U.S. remains the most significant defense spender by a factor of three, providing time for managed competition rather than panic. The second critique argues that discussing risk can foster self-fulfilling prophecies. The response is focused on education: being risk-aware does not equate to being alarmist. By teaching students to distinguish between capabilities, satisfaction, and hierarchy—and to quantify each—we diminish the urge to lump everything under "trap" narratives. This reframing doesn't deny the danger; it directs attention and resources to the areas where policy can still be effective.

There's also a practical communication benefit. Policymakers and campus leaders may ask for "one number"—the date when the transition happens. Resist this request. Instead, offer the initial pair: China's share of world output versus America's share of military expenditures. Then add two more: the U.S.-China shares of global R&D and the rise of Asia's overall PPP share. Teaching these four figures together clearly illustrates why Asia's transition is a series of gradual shifts, not a specific date to mark. This also naturally leads to the "so what" for education: diversify student mobility, strengthen research pipelines to withstand policy shocks, and establish institutions that can endure lengthy disagreements. This is a better message for ministers and boards than a doomsday clock.

We should conclude where we started—with the slope indicated by the numbers. Economic weight is shifting east; military and alliance weight still heavily favors the west; research capacity is converging unevenly; and satisfaction with the rules changes by sector and circumstance. In this environment, the role of educators is not to predict a date but to prepare the next generation to operate on uneven terrain. That means courses that teach theory alongside measurements, partnerships that hedge without retreating, and budgets that create redundancy where choke points emerge. It also requires avoiding dramatic language. If we can keep students focused on the critical axes—capabilities, satisfaction, hierarchy—then the classroom can become a place to practice the policy we need: patient, evidence-based, and adaptable. The transition is not a cliff to fall from; it is a gradual descent that can lead to a broader, more stable ground for learning and exchange, as long as we maintain our footing.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

DiCicco, J. M. (1999). The evolution of the power transition research program. Journal of Conflict Resolution. (Sage).

DiCicco, J. M. (2017). Power Transition Theory and the Essence of Revisionism. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics.

East Asia Forum. (2025, September 14). Asia's power transition is a process, not an event.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2025). World Economic Outlook Datamapper: GDP based on PPP, share of world.

IMF, Asia and Pacific Department. (2025, April 24). Regional Economic Outlook for Asia and Pacific.

National Science Board (NSF NCSES). (2025, July 23). Global R&D and international comparisons.

National Science Board (NSF NCSES). (2025, July 23). Publication output by geography and scientific field.

Open Doors/IIE. (2024, Nov.). International students in the United States (2023/24).

SIPRI. (2025, April 28). Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2024. Fact Sheet.

Stanford HAI. (2025). AI Index Report 2025.

US BIS / CSIS analyses (2023–2025). Semiconductor and AI export controls to the PRC.

ASEAN Secretariat. (2024, Sept. 24). RCEP High-Level Dialogue remarks.

Comment