From Push to Pull: China’s Soft Power Now Runs on Experiences, Not Institutions

Input

Modified

China is moving from messaging abroad to pulling audiences in Visa easing, platform virality, and museum upgrades turn curiosity into visits and study Schools should swap institutes for short, place-based exchanges with clear safeguards

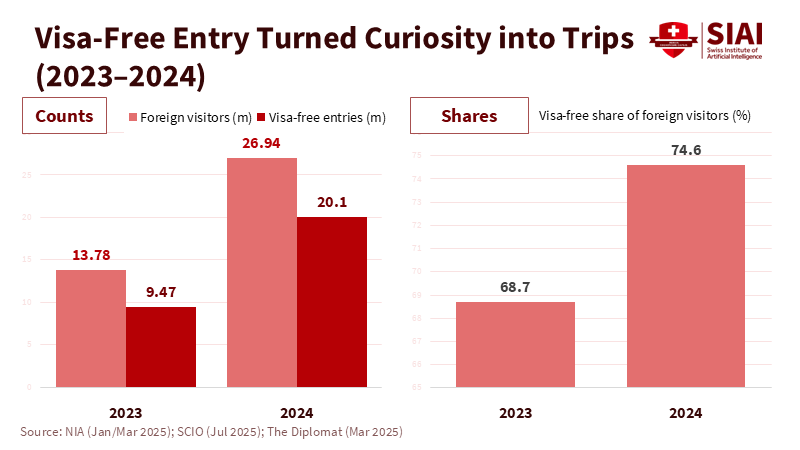

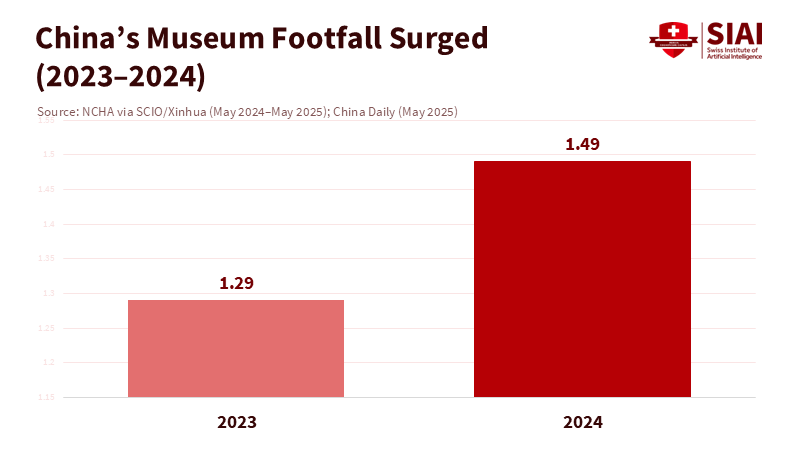

In 2024, China’s museums attracted about 1.49 billion visits, surpassing the total populations of Europe and North America. Meanwhile, the country welcomed around 26.94 million foreign visitors, nearly doubling the previous year's figure as visa-free policies expanded and eligible travelers enjoyed more extended transit stays of ten days. During this time, the number of Confucius Institutes in the U.S. dropped to fewer than five, down from about 100 in 2019. Together, these figures mark a clear departure from the old strategy. Instead of spreading ideology through overseas classrooms, Beijing is creating a magnetic pull at home with museums, significant events, scenic spectacles, and culinary and heritage routes, making it easier for foreigners to visit on their own terms. The approach has changed, but the goal remains the same. It sees attraction as a personal choice, carefully curates experiences, and allows travelers to share their own stories. Soft power is now an itinerary, not a lecture.

From Exporting Messages to Importing Audiences

The most visible sign of the old outreach, the Confucius Institutes, peaked at over 500 worldwide and then declined, especially in democratic nations where worries about governance and academic freedom led to closures. In the U.S., federal funding cuts accelerated the decline to single digits; in Europe and Australia, political scrutiny and safety assessments prompted similar withdrawals. Yet this gap did not lead to silence. Beijing has quietly diversified its channels, from China Cultural Centers to partnerships between universities and scholarships for students in the Global South, while focusing on the area where consent is clearest: travel. The key move is not a new logo but a series of changes in visa policy that increase the likelihood of curious outsiders actually arriving.

Policy sequencing is essential. In late 2023 and throughout 2024, China added visa-free entry for more nationalities on top of an extended 240-hour visa-free transit through 60 ports. This message was further amplified by the state’s “Nihao! China” campaign and a tourism promotion blitz in 2025, offering subsidies and familiarization trips. The impact was clear. In 2024, the country recorded 26.94 million foreign arrivals and 131.9 million total inbound tourist trips when broader counting methods were applied. In the first half of 2025, foreign nationals made about 38 million cross-border trips, with visa-free entries increasing by over half compared to the previous year. Although these numbers have not yet reached pre-pandemic levels, the trend is unmistakable. Note: “foreign visitors” and “inbound tourists” are different statistical categories in Chinese reporting. The former excludes residents from Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan and counts individuals, while the latter often counts trips and may include those visitors.

This shift from messaging campaigns to curated experiences is a response to a decade of political challenges. The decline of Confucius Institutes in the U.S. and Europe did not diminish interest in the Chinese language or culture; instead, it redirected interest toward environments where visitors volunteer, pay for, and share their experiences. The logic is straightforward: it’s easier to trust a city than a classroom. Shanghai’s museums and food streets, Xi’an’s night markets, Zhangjiajie’s glass bridges, or Harbin’s winter festival make a more compelling case for “China as lived” than any brochure could. The state’s role has shifted from teaching to building infrastructure, creating more and better venues, simplifying entry, combining culture with leisure, and increasing the chances that a smartphone camera captures a compelling story.

The Platform Play: Content as a Magnet

If tourism is the short-term lever, platforms serve as the ongoing engine. TikTok/Douyin retained its position as China’s most valuable brand in 2025. This indicates that the country’s most substantial cultural influence originates not from a state broadcaster but from a global short-video platform that thrives on engaging visuals, iteration, and feedback from its community. In this context, soft power appears less like a national campaign and more like an algorithm that promotes Harbin’s ice sculptures one week and Dunhuang-inspired fashion the next. When this content leads to travel—such as bookings through Trip.com’s inbound initiatives or viral videos from city tourism boards—the distinction between culture, commerce, and movement blurs. The channel is private, but the result is public.

Domestic cultural resources support this magnetism. By the end of 2024, China had 7,046 museums, with about 1.49 billion visits that year. Over 90 percent of these museums offered free admission, and science and technology museums alone attracted more than 100 million visits. This scale allows for focused curation and responsiveness to seasonal trends. When Harbin turned its freezing weather into a popular attraction, visitor numbers and revenue surged. Provincial data show increases during holidays, and national media now refer to “ice-and-snow” tourism as a key winter economy. This is not just a temporary event but a model: invest in quality venues, create moments for social media, and let policy reduce obstacles to entry. Soft power is embedded not in slogans but in design choices, signage, food options, and timely translations on museum exhibits.

The “pull, don’t push” model is not unique to China. Korea’s decade-long K-pop rise illustrates how cultural industries can grow globally by improving domestic production and distribution before gaining worldwide popularity. K-pop didn’t force its way into playlists; it optimized for them. Beijing’s lesson is to trade moral persuasion for market fit—use platforms and local experiences to allow foreigners to choose Chinese culture for themselves. Recent data from the Korean industry—surges in exports, increased royalty collections, and support from agencies like KOCCA—show how a government can facilitate growth without dictating content. China’s approach focuses less on pop stars and more on museums, cuisine, city branding, and major travel routes, but the underlying logic is similar.

What This Means for Educators and Policymakers

Universities and school systems should shift their focus away from trying to recreate Confucius-style classrooms and instead develop exchanges centered around real-world production and experiences. The most resilient programs will offer credit, be short-term, and focus on hands-on experiences—like summer design studios in Shenzhen makerspaces, language courses that include museum fieldwork in Nanjing, or environmental studies that use Chongli’s post-Olympic snow economy as a testing ground. The goal is not to teach China in abstract terms but to let students learn within active Chinese systems—cultural venues, logistics networks, and civic services—which are often the memorable experiences visitors share. Administrators should complement this with agreements to share data that quantify outcomes (such as contact hours in Chinese, assessed projects, and visitor satisfaction), while ensuring that academic freedom is maintained. The evidence that inbound travel is rising due to policy changes implies that resources from the Chinese side will be available; the education sector’s task is to facilitate meaningful connections and promote reflection.

Ministries of education can go further by recognizing the diplomatic value of “study-in-place” micro-credentials, along with tourism-related learning. A museum curation micro-credential co-issued by a Chinese cultural body and a foreign university is not propaganda; it’s a transfer of skills that is valuable in creative industries. Scholarship programs aimed at Belt and Road partners already exist and could be directed toward project-focused cohorts rather than scattered placements, making outcomes more straightforward and lowering costs. Early reports suggest that Chinese higher education institutions are attracting an increasing number of students from the Global South, particularly those with science-oriented curricula. If this trend continues, pairing scholarships with themed cohorts (such as digital heritage, urban sustainability, or film production) would align incentives with the new soft-power mix.

Critics may argue that platforms can spread propaganda and that tourism can efface reality. They have a point, and these risks need careful management. TikTok use has been linked in some contexts to increased receptiveness to pro-China narratives, which is a troubling statistic for educators and regulators who must ensure the integrity of information. However, the solution is not to retreat into distrust but to create countermeasures: require transparency for state-sponsored content in campus communications, incorporate media literacy into exchange programs, and demand data protection and grievance procedures in agreements with Chinese partners. Plus, because the pull model is experience-based, it is also open to scrutiny. A museum exhibit can be reviewed, an itinerary can be evaluated, and a translation can be corrected. The strategy of persuasion has shifted to places and products, where independent observations can be easily shared.

There is also a practical reason to welcome this change. The combination of policies that broadens visa-free access, improves airport transit, and supports inbound promotions is measurable and reversible. Its success does not depend on resolving complex political issues. The state can track arrivals, monitor visitor stay times, and analyze demand by adjusting routes and seasons. Universities and cultural partners can connect to this cycle through pilot programs that gather substantial evidence rather than relying on impressions. The old approach, which involved establishing a branded institute on campus, prioritized political identity as its primary focus. The new strategy centers around user experience and making the traveler’s story the main takeaway. When a visitor shares their experiences with friends back home, soft power grows as social proof. Policymakers should ensure that this process is trustworthy enough for skeptics to review and transparent enough that fans feel free to engage with it.

The key statistic—1.49 billion museum visits in China, nearly 27 million foreign visitors, and a significant decline in classroom programs in the U.S.—illustrates the ongoing change. China no longer asks strangers to sit and listen; it invites them to stand up and explore. This shift matters for education because places impart knowledge differently than people do. If we accept that soft power today relies on consent and curated experiences rather than strict teachings, the correct response is to design learning that engages travelers where the evidence is found: in museums and markets, on trains and riverside walks, in winter festivals and design studios. Policymakers should maintain access for curiosity, and educators should ensure that the terms of learning remain clear and transparent. The challenge is not to out-debate China’s narrative; it is to determine if we are willing to experience it firsthand and allow our students to record what they discover.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Brand Finance. (2025, May 9). TikTok/Douyin retains its crown as China’s most valuable brand for the second year.

China Daily. (2025, Jan 3). Year-ender: China’s tourism highlights of 2024.

East Asia Forum. (2025, Sept 13). Confucius Institute decline signals China’s soft power shift.

Government of China / SCIO. (2024, May 17–18; 2025, May 19). Museums in China register 1.29 billion (2023) and 1.49 billion (2024) visits; 7,046 museums by end-2024.

Kao, G. (2023, Aug 21). The rise of K-pop, and what it reveals about society and culture. Yale News.

National Association of Scholars. (n.d.). After Confucius Institutes; How many Confucius Institutes are in the United States? (report pages).

National Immigration Administration / Gov.cn. (2025, Jul 16; 2025, Jul 30). H1 2025 cross-border trips and visa-free entries; 2024 foreign visitors 26.94 million; visa-free transit to 240h and more ports.

Reuters. (2024, Jan 4). China’s ‘ice city’ Harbin draws record tourists over New Year holiday.

SCMP. (2025, Jul 7; Jul 16). Visa-free policy pays dividends; H1 2025 entries surge.

State Council Information Office (SCIO). (2023, Dec 28). We carried out the “Nihao China” campaign…

The Diplomat. (2024, Aug 24). The Rise, Decline, and Possible Resurrection of China’s Confucius Institutes.

Trip.com Group / TTG Asia. (2023, Nov 22). Trip.com joins “Nihao China” campaign to promote inbound tourism.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2023, Oct 30). With nearly all U.S. Confucius Institutes closed… (GAO-24-105981).

Xinhua / China Daily Gov Service. (2025, Apr 21–22; 2023, Dec 6). Tourism promotion campaign highlighting inbound travel; “Nihao! China” events.

Comment