Three Steps Forward: Why the UK-India Trade Pact Is a Working Model of Mutual Advantage

Input

Modified

The UK–India pact swaps targeted tariff cuts for larger services and mobility gains Phased quotas protect adjustment while amplifying each side’s comparative strengths Biggest risk: an EU–India deal; move fast and fund skills to preserve advantage

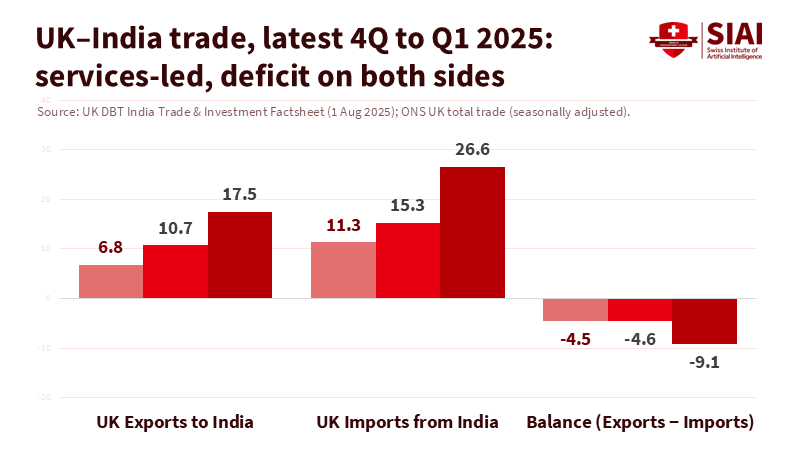

Every trade agreement promises gains on paper. Few deliver results that feel like progress from both sides. One statistic highlights the stakes: in the four quarters leading to Q1 2025, total UK-India trade in goods and services hit £44.1 billion, with services now accounting for over half of this trade; however, the UK still faced a £9.1 billion bilateral deficit. This unusual situation, characterized by strong service connections alongside ongoing gaps in goods and services, highlights why a deal that reduces tariffs while enhancing mobility and market access can benefit both partners. The agreement, signed in late July 2025, with its strategic foresight, reduces India's steep duties on cars and spirits, facilitates regulatory and digital access, and clarifies rules on business mobility. In simple terms, the UK relaxes some protections to advance in its strongest sectors, while India reciprocates by conceding in areas where it will gain more in others.

The Arithmetic of Mutual Advantage

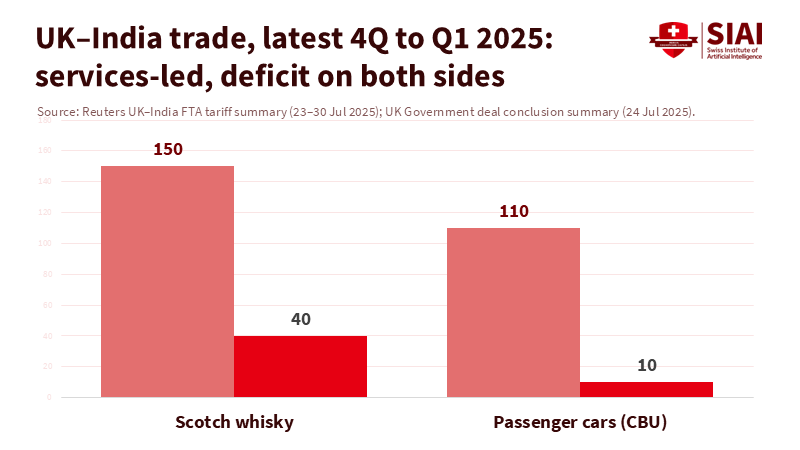

What makes this pact effective is not romance but math. India's import duties on UK motor vehicles, once as high as 110%, will decrease to 10%within specific quotas. The notorious 150% tariff on Scotch whisky will be immediately reduced to 75% and then to 40% over the next ten years. These two actions alone adjust the pricing of high-value UK exports in a market of 1.4 billion consumers while keeping India's protective barriers sufficiently high outside the quotas for smooth adjustment. In return, India secures better access to services and gradual reductions on tariff lines that align with its growing manufacturing base. The UK's projections suggest significant growth in the automotive, beverage, and advanced services sectors, with long-term GDP gains of around £4.8 billion annually by 2040. India's commerce ministry frames the outcome as duty-free or reduced-duty coverage across about 90% of relevant tariff lines while protecting sensitive sectors. This is a clear exchange, not a giveaway, and it paints a promising picture for the future of these sectors.

The services aspect is even more crucial than the tariff headlines. Approximately 1,000 Indian companies already employ around 100,000 people in the UK, and Indian services exports to Britain reached nearly US$20 billion in 2023. Clarifying short-term business mobility, including what counts as permissible work, who can enter under what conditions, and for how long, eliminates the gray areas that delay the actual delivery of services contracts. For universities and skills providers, this creates a real market for executive education, micro-credentials, and joint research projects tied to the sectors the deal supports. For companies, it reduces obstacles and legal risks. The net effect links high-value services to tariff reforms in goods, making the "two steps back, three forward" metaphor more than just rhetoric.

Comparative Advantage, Made Concrete

Comparative advantage, a fundamental economic principle, seems abstract until a tariff line changes. Here it becomes tangible. The UK's advantages in premium automobiles, spirits, higher education, and legal and financial services now have a more straightforward path into India's middle-class market. India's strengths—in IT-enabled services, engineering goods, textiles, and a range of entrepreneurial firms—gain more reliable access to the UK. This access is complemented by provisions on digital trade and public procurement that India has rarely adopted to this extent. The quotas and phased reductions are not flaws; they act as buffers that allow both sides to capitalize on gains while their industries adjust. The result is a deal tailored to the time frames needed for capital investment, training, and supply chain redesign rather than the news cycle. It is also the first major UK agreement post-Brexit that directly connects tariff reduction to a chapter on services mobility, a connection often missing in older deals.

Numbers illustrate the potential benefits. The Department for Business and Trade estimates that tariff reductions could increase UK beverage and tobacco exports by roughly £700 million compared to a baseline without the free trade agreement, with whisky as the likely leader. Sector groups go further: the Scotch Whisky Association claims that a freer market could generate up to £3.4 billion in annual tax revenue for Indian governments as formal sales rise and illegal alternatives diminish. Regarding vehicles, commentary from Parliament and industry indicates a gradual improvement: the 10% end goal is significant, but quota amounts and model-by-price thresholds suggest it will take time before British carmakers feel the full impact. This critique is valid, but it addresses timing rather than direction. The deal moves in the right direction and solidifies this in law.

The EU Wildcard—and How to Hedge Against Preference Erosion

The main strategic risk comes not from the UK-India pact but from the next one. EU-India talks picked up pace in September 2025, with officials noting that over half the chapters are already provisionally closed and discussions are ongoing for a year-end push. If Brussels secures a package that mirrors the UK's tariff and regulatory victories, the UK's preference margin in India will shrink. The anticipated GDP gain of £4.8 billion by 2040 is an economy-wide figure that assumes some competitive edge. Our rough estimate, holding world demand constant and using a simple gravity-style elasticity of substitution of 3 for differentiated goods, suggests that if the EU matches the UK's tariff schedule, the UK's additional export boost to India in those categories could be reduced by 20–30% compared to a scenario with only the UK involved. This does not negate the gains; it redistributes them across multiple partners and compresses profit margins.

Policy strategies are available. First, it's crucial to implement quickly. Preference erosion is a race between legal texts and business actions. The sooner tariff cuts and mobility chapters are put into effect, complete with clear guidance for SMEs, the more contracts can be signed before competitors achieve the same advantages. Second, it's essential to capitalize on the areas where the UK has a qualitative edge, not just in tariff relief: legal service standards, fintech environments, mutual recognition in niche professional qualifications, and research partnerships linking universities to industry projects in autos, clean energy, and aerospace. Third, it's vital to protect and strengthen the components that India values most—predictable mobility for service providers and clear digital rules—since rivals will find these hardest to replicate swiftly. Finally, it's necessary to design pathways from campuses to factories so that the skills and research enabled by the agreement are produced at scale. If the UK's advantage lies in its people and ideas, it must be funded accordingly.

Translating this for education and workforce leaders means planning for actual demand. UK institutions should anticipate growing interest from Indian firms looking for executive courses in systems engineering, electric vehicle powertrains, supply chain analytics, and compliance with EU and UK carbon and product standards. The electric vehicle quotas alone suggest a multi-year need for technicians, homologation specialists, and software engineers who can navigate different standards. On India's side, universities can leverage the pact's procurement and innovation provisions to collaborate with UK labs on battery testing, lightweight materials, and sustainable packaging—areas where tariff cuts on equipment and more precise IP terms facilitate cooperation. None of this happens automatically. It requires ministries and regulators to provide course design templates aligned with the sectoral opportunities of the deal, and for quality agencies to recognize micro-credentials aligned with the categories of service suppliers in the mobility chapter.

Above all, educators should view the agreement as a practical guide for learning. When tariffs fall on vehicles and spirits while access to services expands, curricula should reflect that combination: business schools pairing trade law with supply chain labs; engineering faculties incorporating tariff-driven bill of materials modeling into capstone projects; public policy schools simulating "preference erosion" when a second partner, such as the EU, finalizes a similar deal. The goal is not merely to teach the treaty's clauses as civics but to prepare students to leverage them responsibly: faster localization of parts, better compliance, quicker market entry, and ethical frameworks for mobility that prevent exploitation. If the agreement changes incentives, education must guide talent in the same direction.

Consider the UK-India pact a model not because it is flawless but because it is balanced. It lowers the barriers that matter most—autos, spirits, complex services—at a pace the economies can manage. It places mobility and digital rules at the forefront, where modern trade occurs. It acknowledges that comparative advantage is dynamic and that both parties benefit by focusing on their strengths while preparing to improve their position. The opening statistic—£44.1 billion in two-way trade with a large UK deficit—seemed stagnant before the deal. With the pact signed and implementation underway, it now resembles a pipeline that can facilitate higher-value exchanges in both directions. The real risk now is not the agreement itself; it is standing still while others follow suit. The correct response is speed, attention to detail, and investment in people. If we treat this agreement as a framework for skills and partnerships rather than a trophy, the promise of "two steps back, three forward" can become a regular practice, not just a headline.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Department for Business and Trade (UK). (2025, July 23). Technical note of the preliminary economic impacts of the UK–India Free Trade Agreement.

Department for Business and Trade (UK). (2025, July 24). Impact assessment of the Free Trade Agreement between the UK and India (Executive summary).

Department for Business and Trade (UK). (2025, July 24). UK–India trade deal: conclusion agreement summary.

House of Commons Library. (2025, August 19). UK–India Free Trade Agreement (CBP-10258).

Office for National Statistics / Department for Business and Trade (UK). (2025, August 1). India—Trade and investment factsheet.

Reuters. (2025, July 22). India, UK to sign free trade deal during Modi's visit, cut tariffs on whisky and garments.

Reuters. (2025, September 9). India, EU push to close gaps in trade talks as year-end deadline looms.

Scotch Whisky Association. (n.d.). India and Scotch Whisky—Why tariffs matter.

Times of India. (2025, September 9). India–EU FTA: Over 60% of chapters finalised, says Goyal.

UK Government. (2025, July 23). UK–India Free Trade Agreement: Business Mobility explainer.

Press Information Bureau (Government of India). (2025, July 27). India–UK CETA—Key features and tariff line coverage.

Comment