Same Cash, Different Rails: What Stablecoins and Money Market Funds Mean for Education Finance in 2025

Input

Modified

Same cash backbone, different rules: MMFs pay yield; stablecoins move money fast Receive tuition via regulated stablecoins, then auto-sweep into MMFs/tokenized T-bills This two-rail setup cuts cross-border costs, speeds settlement, and protects budgets

This year, one number tells the story: about $7.3 trillion sits in U.S. money-market funds while dollar stablecoins hover near $280 billion, and both amounts are mainly parked in short-term Treasuries. The assets underlying these two forms of cash are converging on the same government liabilities, even as the rules that govern them diverge. For universities, schools, edtech platforms, and scholarship networks that transfer money across borders on a daily basis, this is not just a curiosity. It is a new operating environment. The central question is no longer whether stablecoins are similar to money-market funds. It's about how to combine them safely to make tuition payments cheaper, scholarship disbursements faster, and institutional treasury more resilient, without adopting the risks of cryptocurrency or the complacency of traditional cash. The benefits are clear: by treating these instruments as complementary, education finance can achieve speed, transparency, and efficiency at scale.

Why the "same cash" claim misleads—and still matters

At first glance, the user experience seems similar. A money-market fund (MMF) and a regulated dollar stablecoin both offer easy on-ramps, same-day liquidity, and a price that closely follows one dollar. However, they differ when it comes to law and incentives. MMFs are investment products regulated under SEC Rule 2a-7. They are subject to daily and weekly liquidity requirements, as well as new 2023 reforms that mandate liquidity fees and eliminate gates to reduce run dynamics. Yields vary with policy rates; the Crane 100 index shows around 4.1% seven-day yields in early September 2025, with large government MMFs posting similar returns. Payment stablecoins, on the other hand, became expressly non-interest-bearing under the U.S. GENIUS Act of 2025, which also imposes reserve and disclosure requirements and treats issuers as financial institutions for anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing purposes. The outcome is straightforward: MMFs pay interest, while payment stablecoins do not. This distinction is by design. Schools should view one as a tool for yield and the other as a means of movement, not as substitutes.

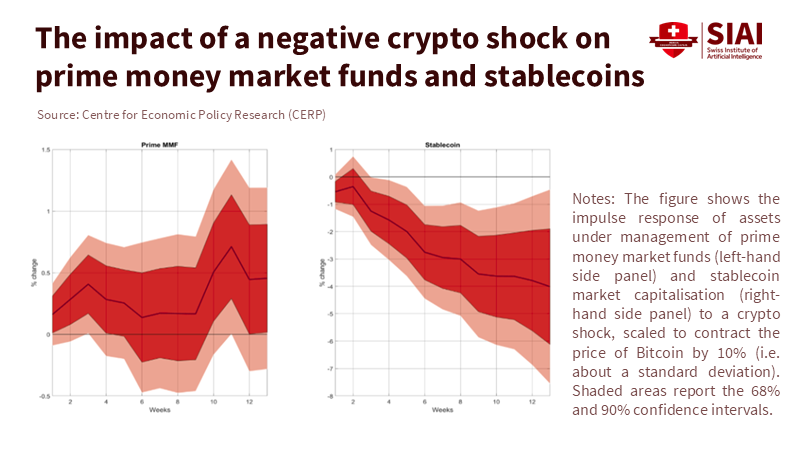

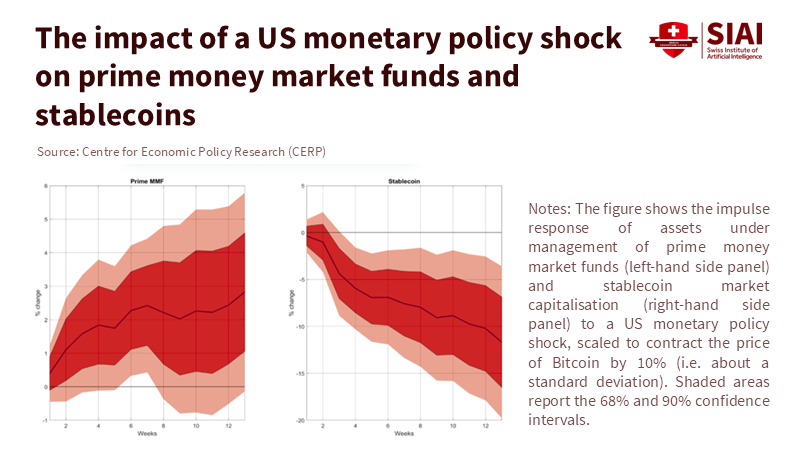

The remaining similarities have significant policy implications. Both instruments offer one-for-one redemption and engage in liquidity transformation, which is why researchers at the New York Fed express concern that MMFs and stablecoins can share the same run mechanics despite their different structures. This difference becomes evident when guarantees are tested: USDC's well-documented de-peg to $0.88 during the SVB weekend in March 2023 illustrates that "money-like" is not equivalent to "money." MMFs, in contrast, did not de-peg; they absorbed large inflows as deposits exited banks, thanks to liquidity driven by rules and portfolios focused on government securities. In practice, a school treasurer can rely on the stable pricing of MMFs with regulatory stress measures in place; however, a bursar accepting stablecoins must actively manage peg and platform risk, with policies for immediate conversion. The exact cash is underneath, but there are different failure modes. That is the reality of operations.

Flows reinforce the point. From 2023 to 2025, MMFs experienced record inflows, amounting to about $1.2 trillion in 2023 alone, pushing assets to new highs as depositors sought yield and safety after stresses in regional banks. By January 2025, total MMF assets approached $6.9 trillion and have since risen past $7 trillion. Stablecoins expanded along a different path; they are not used as domestic sweep destinations but rather as global transaction media, especially in regions where access to dollars is limited. Dollar-pegged stablecoins are now clearing transaction volumes that big banks cannot ignore, with their market cap around $280 billion as of early September 2025. Where MMFs yield a few percent, stablecoins save on transaction friction, especially across borders. Education systems sit at the intersection of these flows; they collect, disburse, and hold funds. By combining these rails, they can translate basis points and seconds into budgets and enrolled students.

Where education meets the new cash stack

Cross-border education is a significant and growing phenomenon. About 6.9 million students study outside their home countries, with the OECD reporting that most enroll in OECD destinations, and nearly half choose the U.S., U.K., Australia, or Canada. However, the average global cost of sending remittances—which serves as a decent proxy for many tuition and family support payments—was about 6.5% in Q1 2025. Digital services reduce that to around 5%, yet they still leave substantial costs on five-figure bills. If 10% of the world's internationally mobile students (approximately 690,000) paid $10,000 in annual tuition from abroad and lowered costs from 6.5% to 1.0% by using regulated dollar stablecoins for same-day conversion, the total savings would be close to $3.8 billion (calculated as $10,000×(6.5–1.0)%×690,000). That is money for textbooks, labs, and financial aid. The payment aspect benefits from the speed of stablecoins, while the treasury side should not hold funds in them. Sweep policies create a link between the two.

The sweep represents an essential guideline: receive in the fastest method, hold in the safest yield. For universities and larger districts, this means automatically converting payment stablecoins into either (i) bank deposits that quickly move into MMFs or (ii) compliant tokenized T-bill funds that now exist on public chains but act like cash-equivalent securities. This latter market, although still small, has grown rapidly, with tokenized Treasuries estimated to reach $7–8 billion by mid-2025 and total tokenized real-world assets, excluding stablecoins, in the mid-$20 billion range. Properly labeled and held, these instruments allow a bursar to earn a yield close to the policy rate with instant settlement back to the payment method when required. Schools should not seek DeFi yield; they should stick to government-only exposures or regulated MMFs, documenting the conversion process down to the minute. That is how to implement risk-aware cash management.

The benefits of inclusion are sharper downstream. Sub-Saharan Africa already sees a larger share of retail-sized crypto transfers than the rest of the world, with stablecoins accounting for roughly 43% of the region's crypto transaction volume. In Nigeria alone, an estimated $59 billion in crypto transactions occurred from July 2023 to June 2024. For distance-learning providers and scholarship NGOs that assist families in countries dealing with double-digit inflation, stablecoins serve as a practical dollar buffer. The GENIUS Act's prohibition on issuer-paid interest limits stablecoins to functioning as "digital cash," which is precisely what a tuition payer needs. At the same time, AML/CFT obligations now apply to issuers. This combination of low-friction payments with more apparent oversight supports a policy approach that encourages regulated acceptance in areas with weak banking infrastructure. This is contingent on institutions converting promptly and holding custody outside exchanges.

A policy blueprint: two rails, one standard

To implement this effectively, education finance requires a targeted blueprint that focuses on clear rules. First, admissions offices and bursars can test the acceptance of stablecoins for cross-border payments through licensed payment processors that convert them to fiat or MMFs upon receipt, thereby avoiding institutional wallets on trading platforms and keeping no balances idle overnight on-chain. The processor must incorporate KYC/AML screening that is integrated into the GENIUS framework. The treasury should set a maximum "crypto exposure window," for example, thirty minutes from payment to conversion, and test it against traffic spikes, banking hours, and network congestion. This should be documented as a control measure, not a wish. Second, institutions should prioritize MMF-centric operating reserves, as they still offer returns and operate under mature rules. A 4% yield on large sums provides real financial relief in lean budget years. Third, auditors must understand the differences: payment stablecoins are not deposits, not MMFs, and not securities; tokenized T-bill funds are. Labels and policy notes need to be consistent.

Critics may argue that stablecoin rewards offered by platforms could blur the non-interest rule, reducing the clarity we seek and tempting institutions into risky areas. They are justified in their concerns. The GENIUS Act prohibits issuers from paying interest. Still, a developing loophole involving exchange rewards has already led to bank lobbying and questions from the Treasury, indicating more rule-making is possible. The education sector should steer clear of these complexities: if yield is essential for short-term cash, turn to government MMFs or clearly labeled tokenized T-bill funds through qualified custodians. If speed is crucial for certain transactions, use payment stablecoins and implement sweep strategies to ensure timely transactions. Keep the functions clear. By doing this, schools can avoid competing with banks for deposits while still providing lower fees and faster services to students and families.

Another concern is the risk of complications during times of stress. What happens if a stablecoin falters or a blockchain halts? A real-world answer comes from the SVB failure weekend, when USDC dropped to $0.88. This highlights why acceptance should be a payment choice, not a balance-sheet gamble. Institutions can establish triggers—if a stablecoin deviates by more than, say, 50 basis points from par for five minutes, acceptance can pause. Alternative options (such as wires, credit cards, or bank transfers) can be made available. On the holding side, MMFs have managed both COVID-era and 2023 banking stress, utilizing rule-driven liquidity and new fees that place redemption costs on those who engage in runs. The key policy point of using both rails is to shift volatility into the payment leg while maintaining yield and principal in instruments already within your auditing and risk management framework.

Finally, equity is essential. International students and low-income families face the harshest frictions in the current system: weeks of settlement delays, unexpected correspondent fees, and high overall costs. With the global average remittance fee near 6.5%, even a digital service's average of about 5% is significant. When a student relies on relatives across borders to fund tuition, those percentages can be the difference between enrolling and deferring. Stablecoin systems can reduce those frictions, while MMFs can help place yield back into institutional support funds. The perspective here is not "crypto for crypto's sake." It emphasizes the choice in payment methods alongside disciplined treasury management. This approach enables the education sector to capitalize on the benefits of the new cash landscape while mitigating associated risks.

Two facts can coexist. The first is that dollar stablecoins and money-market funds now rely on the same U.S. Treasury foundation, and together they are changing how dollars are moved. The second is that they operate under very different rules: one rail generates yield and absorbs surges, while the other transfers value quickly and efficiently without paying interest. If we conflate these differences, we risk either incurring liabilities or missing opportunities. If we keep them distinct but connected—receiving funds via the fastest method and holding them for the safest yield—we can reduce the cost of education for families while strengthening institutional budgets without new taxes or tuition hikes. With MMFs totaling around $7 trillion and stablecoins about $280 billion, the best policy response for education is not to choose one over the other. It is to connect the two, test the connections, disclose the paths, and allocate the savings where they truly matter: in classrooms, labs, and scholarships.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Aldasoro, I., Cornelli, G., Gambacorta, L., Ferrari Minesso, M. (2024). Stablecoins and money market funds: Less similar than you think. VoxEU/CEPR.

Anadu, K., et al. (2023). Are Stablecoins the New Money Market Funds? Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Staff Report No. 1073.

Center for Global Development (2025). How Stablecoins Could Further Weaken Africa’s Public Finances.

Crane Data (2025). Crane 100 Money Fund Index: Yields.

Investment Company Institute (2025). Weekly Money Market Mutual Fund Assets (Sept. 4).

Morgan Stanley (2024). Digital (De)Dollarization?

RWA.xyz (2025). Tokenized Real-World Asset Analytics (market dashboards, Sept. 10).

SEC (2023). Money Market Fund Reforms; Amendments to Rule 2a-7 (Press Release 2023-129; Final Rule).

U.S. Department of the Treasury (2025). Request for Comment related to GENIUS Act.

UNESCO (2025). Record number of higher education students highlights global need for recognition of qualifications.

U.S. Federal Reserve—OFR (2024). U.S. Money Market Funds Reach $6.4 Trillion at End of 2023 (Mar. 26).

U.S. Federal Reserve (2025). Financial Stability Report: Funding Risks (May 7).

WilmerHale (2025). What the GENIUS Act Means for Payment Stablecoin Issuers (Client Alert, July 18).

World Bank (2025). Remittance Prices Worldwide, Q1 2025 (main site and Issue 49 report).

Reuters (2023). USDC breaks dollar peg after SVB exposure revealed (Mar. 11).

Reuters (2025). U.S. Senate passes GENIUS Act (June 17).

MacroMicro (2025). World: Stablecoin Market Capitalization (Sept. 4 reading).

Comment