Who Owns the Water? Educating for Power in the Age of "Blue Territory"

Input

Modified

Education now depends on “blue territory” where subsea cables and sea lanes shape daily life Disruptions at Suez and Panama show why we need skills for ports, cables, and maritime law Embed ocean literacy, fund micro-credentials, and plan for outages

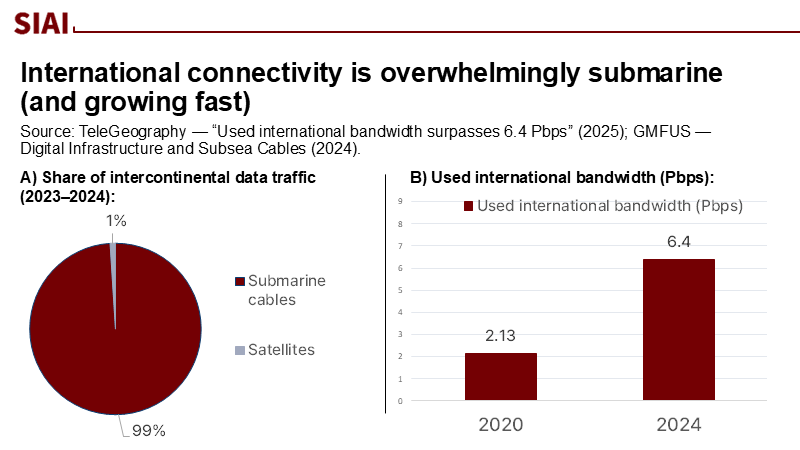

The most critical number in education policy this decade may not come from a classroom. About 99% of the world's international internet traffic travels through submarine cables on the seafloor. This system acts as the unseen backbone of current learning, testing, payroll, research, and student services. However, it is vulnerable to ship anchors, storms, sabotage, and the conflicts among powerful nations at sea. In the last two years, internet traffic has surged again as global bandwidth demand has more than tripled since 2020. Incidents in key waterways have rerouted ships and increased costs. Our schools are not ready for a time when the reliability of education, research, and job markets can depend on events happening deep underwater. The urgency of this issue cannot be overstated. Suppose we keep treating the ocean as a distant backdrop. In that case, we will mislead a generation about an economy and geopolitics that are increasingly influenced by "blue territory," not just borders on maps.

From Coasts to Cables: What "Blue Territory" Really Means

"Blue territory" refers to seeing the ocean as governed areas where states exercise authority, create rules, and secure strategic advantages—without necessarily claiming new land. In the traditional European legal view, maritime rights radiate from land: the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extends 200 nautical miles from a coastline, granting a country special rights over resources. This concept, set out in the Law of the Sea, still underlies maritime governance. However, the reality of power at sea increasingly resembles mobile influence. Carrier groups, logistics hubs, and data cables connect continents regardless of who owns the nearest island. The United States has pledged to maintain 11 aircraft carriers—floating runways that extend reach across the Pacific and Atlantic—while rival nations respond similarly. Education systems, still often based on territorial civics and land-based economics, rarely teach students how law, logistics, and information flow interact in these blue waters.

The stakes are very real. China's naval modernization has advanced quickly, with estimates from the Congressional Research Service forecasting a battle force of nearly 400 ships by mid-decade. Even though overall size and carrier aviation still favor the United States, Chinese shipyards have led commercial shipbuilding orders, capturing about 50% to 70% of the global market depending on the month. This capacity can shift from commercial to military use, supporting a persistent presence at sea. This is blue territory shown through logistics and industry as much as through the number of ships. Our graduates will manage ports, ensure cargoes, code routing software, and regulate emissions. They will also vote on budgets that determine whether their countries can protect the cables and sea routes their jobs depend on.

Every week brings new reminders that the rules at sea are contested. Resupply missions to the Philippines' outpost at Second Thomas Shoal have navigated harassment and collisions. Shipping through the Red Sea has been rerouted around Africa, and drought has reduced Panama Canal capacity. Each disruption prolongs voyages, increases emissions and insurance costs, and ultimately raises prices in school cafeterias and household energy bills. Education policy cannot prevent coast guards from clashing, but it can reduce the frequency of being caught off guard by maritime issues. Students should learn not only that "80% of world trade moves by sea," but also what that means for fiber optic networks, container flows, and emergency planning for schools and universities if digital connections are severed.

The Education Gap: Training for an Oceanic Economy

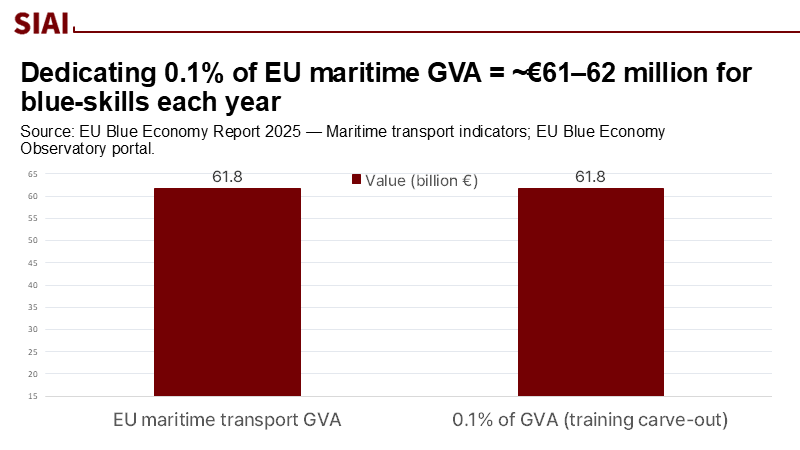

The ocean economy has outpaced global growth for a generation and continues to grow. UN trade estimates indicate it has increased about 2.5 times since the mid-1990s, with record highs in ocean goods and services trade noted in 2023. In Europe, maritime transport generated around €61.8 billion in value added in 2022 and remained steady through 2023. This growth presents a significant opportunity for the future. Yet the talent pipeline is lagging. Industry reports show that shortages of seafarers and officers are at multi-year highs, making recruitment and retention challenging even as fleets and offshore energy projects expand. This gap is not limited to ship crews. There is a shortage of undersea cable engineers, marine data scientists, port-automation technicians, and maritime lawyers across many markets.

Data infrastructure adds to the gap. Submarine cables carry about 99% of international data, and demand continues to rise—used international bandwidth surpassed 6.4 Pbps in 2024, with a 32% annual growth rate since 2020. Investors plan to spend well over ten billion dollars on new cables from 2025 to 2027, mainly led by cloud providers. This situation creates a challenge for the workforce and curriculum. Cable routes must be surveyed, faults detected and repaired, landing stations secured, legal frameworks updated, and resilience incorporated into public services, including schools and universities. Few secondary programs teach cable geography, planning for redundancy, or the basics of maritime law. Even fewer teach students how ship diversions through the Cape of Good Hope affect container schedules, freight rates, and eventually textbook prices and lab supply purchases.

Closing this education gap does not require militarizing curricula. It requires a basic knowledge of the ocean, which is linked to specific career paths. A practical goal is to weave a "coast-to-cable" focus throughout subjects by the upper-secondary level. Students should learn about ocean science and climate, the civics of maritime law and governance, the economics of ports and shipping, and the computing related to routing, resilience, and satellite-to-sea networks. It is our responsibility to ensure that students are well-prepared for the future. If education ministries in coastal economies allocated just 0.1% of maritime transport value added to teacher training and lab improvements, the EU could raise approximately €61 to €62 million each year for blue-skills training and apprenticeships. Such predictable funding would support micro-credentials in port operations, ocean data, and maritime law and enhance dual-enrollment programs with maritime academies—steps that connect education with visible job opportunities.

Policy Moves We Can Make Before the Tide Turns

First, treat "blue territory" as a civics and infrastructure topic, not just a defense issue. Students should learn how EEZs operate, how the Law of the Sea differs from customary navigation norms, and why a carrier group or coast guard presence is not merely a symbol but a means to protect sea lanes and cables that support the software updates and telehealth services communities rely on daily. This involves institutional literacy, which includes understanding which agencies respond when a cable is damaged, how repair ships request waivers, who coordinates traffic rerouting, and how local governments maintain school operations during regional outages. The goal is building confidence under pressure—knowing who does what when blue infrastructure fails.

Second, connect workforce development to the real challenges in the ocean economy. Evidence is clear from shipping disruptions since late 2023: diversions from the Suez Canal raised costs and emissions; drought limited transit through Panama; and rerouting strained ship and crew schedules. Meanwhile, demand for bandwidth on subsea cables has skyrocketed, cloud companies are co-financing new lines, and industry groups are raising alarms about officer and technical shortages. Education ministries can address this issue through three measures: approving maritime apprenticeships that count toward upper-secondary graduation; recognizing micro-credentials for port automation, cable operations, and naval cybersecurity; and increasing scholarship support for career changers entering marine engineering and law. These are not speculative roles; they are crucial positions that keep trade and data flowing when routes are under pressure.

Third, incorporate blue resilience into institutional planning. Universities and school districts routinely prepare for fire, flood, and cyberattacks. They should also prepare for sustained cable outages and shipping chokepoint disruptions. This involves investing in local caches of essential educational content, testing offline learning platforms, and pre-arranging buffers for lab supplies and textbooks. It also consists of forming partnerships with ports and cable landing operators to facilitate student internships and real-time projects in maritime awareness, utilizing open data whenever possible, to monitor vessel movements, weather threats, and cable repair schedules. When students see their coding predict a port backlog or their legal assignments outline the boundaries of an EEZ, they understand how civics, STEM, and law converge at sea.

Possible critiques deserve a response. Some may claim that schools are already overloaded or that shipping and cables are too specialized for general education, or that discussing sea power biases classrooms toward geopolitics. The counterpoint is practical: the ocean economy impacts household expenses, job availability, and the continuity of digital services that schools depend on daily. Teaching it is as non-ideological as teaching about energy grids or public health. Others may argue that maritime topics should only be taught in coastal areas. However, inland communities rely on the same data cables and freight networks; graduates work in supply chain analysis, insurance, and software roles linked to ocean systems. Adding a modest blue element to curricula is proportional to the risk and opportunity presented.

Finally, we should clearly define the strategic context. A mismatch between land-based and maritime assumptions is leading to misunderstandings in Asia's contested waters. While naval numbers and shipbuilding capacity are essential, so are the legal frameworks that influence behavior: whether oceans are commons with navigation rights or extensions of sovereign "blue territory." Understanding this tension does not require students to take sides; it urges them to see how rules are debated—and enforced—far from shore. This kind of literacy helps create more informed citizens and stronger institutions at home.

Nearly all international data crosses the ocean floor. In a time when classrooms, clinics, payrolls, and research all depend on this flow, the question "who owns the water?" is not just a slogan—it's a practical test for education policy. If we disregard the ocean's role in our digital and physical supply chains, we leave students unprepared for unexpected breaks and gradual problems. If we incorporate blue literacy—law, logistics, and infrastructure—into regular education, we create a workforce capable of maintaining cables, optimizing routes, and enforcing fair rules at sea. We also foster communities that can continue teaching and learning when disruptions occur. The solution is straightforward: fund teacher training with a small portion of maritime value added, expand apprenticeships, teach the fundamentals of EEZs and cables, and plan for outages. In essence, let's educate as if the future of our schools depends on the sea—because it already does.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Acuity Knowledge Partners. (2024). Houthi attacks disrupt global trade and shipping routes (blog).

AP News. (2025, Sept. 5). Philippine forces deliver supplies and personnel to disputed South China Sea shoal despite tensions.

Clarksons Research. (2024–2025). Shipyard output and orders (various notes and presentations).

Congressional Research Service. (2025). China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities (RL33153).

East Asia Forum. (2025, Sept. 6). China’s continental identity on a blue horizon.

European Commission, EU Blue Economy Observatory. (2024–2025). EU Blue Economy Report / Maritime transport indicators.

International Telecommunication Union. (2024). Submarine cable resilience backgrounder; Advisory body announcement.

Nautilus Federation. (2025). Recruitment and retention of seafarers (report drawing on ICS/BIMCO data).

NOAA Ocean Exploration. (n.d.). What is the EEZ?

OECD. (2025). The Ocean Economy to 2050; (2016). The Ocean Economy in 2030.

TeleGeography. (2025). Used international bandwidth reaches new heights (blog).

UNCTAD. (2024). Review of Maritime Transport 2024; (2024). Suez and Panama Canal disruptions; (2025). Global Trade Update: Sustainable ocean economy.

UN Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea. (n.d.). UNCLOS Part V: Exclusive Economic Zone.

USNI News. (2025, Aug. 26). Air Boss: Navy committed to maintaining 11 aircraft carriers.

Comment