Tariffs, Taxes, and the Term-Premium Trap: Why the Fed's Next Move Hinges on Treasury's

Input

Modified

Tariffs nudge prices up but can shrink Treasury coupon supply Channel tariff revenue to bills to compress term premia and enable Fed cuts Extending tax cuts swells deficits, hardens long yields, and squeezes education budgets

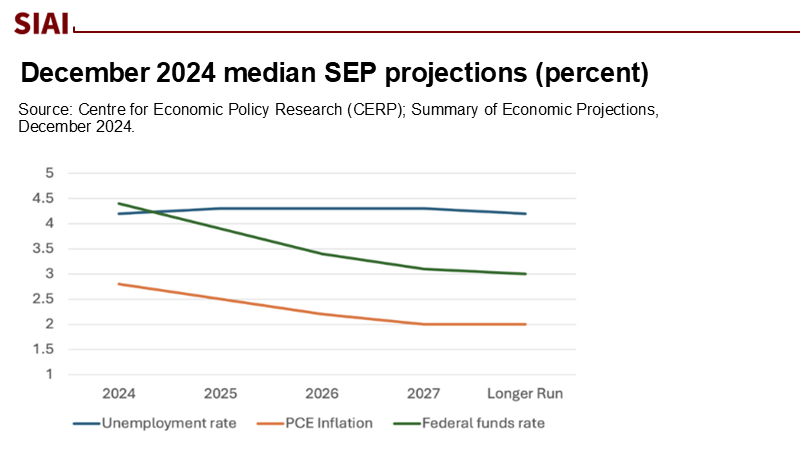

In July 2025, U.S. customs duties collected reached approximately $30 billion, a tripling of the amount from July 2024, suggesting that annual tariff revenue could soar into the hundreds of billions if current policies remain in place. Meanwhile, core inflation has eased modestly, with the PCE inflation rate at 2.6% in June, while the Federal Open Market Committee keeps its interest rate at 4.25–4.50% amid slower quantitative tightening. Changes in financial conditions are also notable, as the Fed's reverse repo facility has dropped close to zero, and the Treasury's General Account has surpassed $500 billion. This could indicate that tariff revenue might significantly affect fiscal liquidity, potentially influencing term premiums and the Fed's ability to lower rates. However, if Congress's extension of the 2017 tax cuts leads to rising deficits that outpace tariff revenue, the situation may change, solidifying term premiums and limiting rate reduction options. Policy design will ultimately shape these outcomes.

Reframing the debate: from prices to the balance sheet

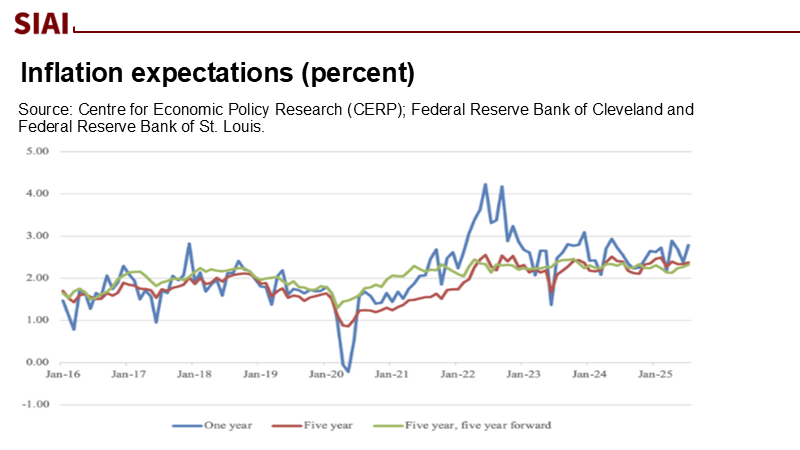

The familiar case against broad tariffs is inflationary: import taxes raise border prices and, with some lag, retail prices, eroding purchasing power precisely when the Fed wants to cement disinflation. That argument is real—but partial. The under-discussed offset is fiscal. Dollar for dollar, tariff receipts reduce the need for the Treasury to sell debt to the public. In a world where the Fed is shrinking its securities holdings and the private sector must absorb more duration risk, even modest reductions in net coupon supply can lower term premia and relieve pressure on long rates. The reframing is timely because 2025's policy mix has pushed the financing question to center stage: tariffs are up, tax cuts have been extended, QT is slowed but ongoing, and money-market liquidity buffers are largely tapped out. The critical question is not "Are tariffs inflationary?"—we know the sign—but whether the fiscal-liquidity channel can dominate enough to make financial conditions looser at the long end even as the Fed watches prices at the short end.

What tariffs can and cannot finance: the revenue math

Reasonable analysts can disagree on the tariff revenue path because it depends on import volumes, compliance, and the stickiness of newly imposed rates. A conservative, evidence-based framework looks like this: as of June 2025, actual receipts since January have totaled approximately $94 billion, roughly 5% of the FY2025 deficit projected at $1.9 trillion. July alone added ~$30 billion; Treasury officials subsequently suggested that annualized revenue could be several hundred billion if recent month-over-month increases persist. An annual take in the $200–$300 billion range—call it 0.7%–1.1% of GDP—would not "fund the government," but it would meaningfully offset net issuance. The plausible upper-tail scenarios cited in policymaking circles, stretching toward $500 billion per year, are contingent on broad coverage and durability; they are not the base case. For policy, the point is probabilistic: even mid-range tariff receipts are large enough to alter the composition and term of Treasury borrowing—if the proceeds are used to suppress coupons rather than to underwrite new structural deficits.

Issuance mix matters more than the headline deficit

Bond markets don't price deficits; they price bonds. The term "premium"—the extra yield investors demand to hold long-term Treasurys over rolling bills—responds to duration supply, risk appetite, and dealer balance-sheet constraints. Research since Vayanos & Vila has shown that changes in the supply of longer-duration paper, holding expectations constant, can materially shift the term structure. Treasury acknowledged as much in recent refunding discussions: as borrowing needs rose, the mix between bills and coupons became a policy lever with market consequences. If tariff revenue is earmarked to lean issuance toward bills and away from coupons, long-term premia should compress; if revenue backstops permanent tax cuts instead, coupon calendars remain heavy, and long yields resist falling even when the Fed pauses. In other words, the same deficit can yield very different outcomes on the yield curve, depending on how it is financed. That is the channel the current debate is missing—and where the tariffs-versus-tax-cuts trade-off bites hardest.

Liquidity plumbing: RRP, TGA, and QT define the runway

The fiscal-liquidity channel sits on top of the monetary floor system. With the overnight reverse repo facility essentially drained, money funds are now significant buyers of bills. This rotation helped absorb the Treasury's short-dated supply without disrupting the fed funds target. Meanwhile, the TGA's rebuild withdraws reserves from the banking system, while a slower QT still nudges reserves down over time. The net effect is a thinner cushion of "ample" reserves and a greater sensitivity of money-market rates to swings in Treasury cash and bill supply. In this environment, using tariff revenue to reduce coupon issuance accomplishes two things at once: it supports reserves indirectly (by moderating TGA swings and duration supply) and it contains long-end yields by easing duration pressure. Conversely, suppose deficits force heavy coupon calendars while the TGA remains elevated. In that case, reserve scarcity risks re-emerge and long yields stay sticky, limiting the Fed's ability to cut without stoking instability. Plumbing will decide how far the fiscal channel can carry monetary policy.

Inflation pass-through: small so far, but rising with time and coverage

Empirically, tariffs raise import prices quickly and consumer prices with a lag that depends on inventories and competitive dynamics. The Federal Reserve staff's real-time work attributes roughly 0.1 percentage points of core PCE inflation to the 2025 tariffs to date—non-trivial, but not an inflation shock. Private-sector estimates cluster around higher eventual pass-through as stockpiles clear and firms regain pricing power, with credible scenarios suggesting that two-thirds of costs will be passed on to consumers. The macro frame is that core inflation near 2½–3% plus firmer term premia leaves the Fed cautious. However, suppose the fiscal-liquidity channel actively compresses long-end yields through its issuance strategy. In that case, the Fed can cut sooner without fueling demand excessively, because financial conditions loosen at the long end of the curve while the front end remains anchored by the policy rate. Inflation is therefore a constraint to manage, not a veto—provided policy keeps the duration-supply dial pointed the right way and refrains from turning tariff proceeds into permanent structural deficits.

Tax cuts versus tariffs: the duel that determines net issuance

The 2025 law, which extends major elements of the 2017 tax cuts, is sizable by post-1980 standards, ranking roughly third when measured as a share of GDP over the relevant horizon. Nonpartisan scoring indicates that the package adds between $2.4 and $2.8 trillion to deficits over a decade, before accounting for any dynamic offsets. Even generous tariff receipts cannot thoroughly neutralize that pressure unless they materialize at the high end of optimistic projections and are dedicated to debt service. In practice, the near-term effect has been an upward revision to the Treasury's borrowing needs and persistent concerns about reliance on short-term bills, both of which complicate plans to lean against duration supply. The conclusion is straightforward: tariffs can be a meaningful financing source, but only if paired with discipline on permanent tax expenditures; otherwise, the term-premium channel dominates, and markets keep the Fed on a tighter leash than inflation alone would imply.

What it means for campuses and classrooms

Why should educators, district administrators, and university CFOs care about the mix of coupons and bills? Because the term "premium" directly impacts capital costs, endowment allocations, and labor budgets. When long-term rates remain high due to heavy coupon calendars, bond-financed campus housing and STEM facilities become materially more expensive, delaying builds or shrinking their scope. Pension discount rates and endowment spending rules suffer whiplash, forcing difficult trade-offs between student support and maintenance. Suppose tariff revenue is used to suppress coupon issuance and compress the term premium. In that case, the cost of refinancing existing higher-ed debt falls, freeing space for instructional hires, technician upskilling, and scholarships. K-12 districts that rely on municipal market access face similar math, albeit via spread to Treasurys rather than the base rate. The policy point is immediate: a Treasury issuance plan that leans to bills while tariffs are elevated is not an abstraction. It is the difference between cutting a tutoring program and green-lighting a digital-learning lab.

Anticipating the critiques—and why design beats dogma

Three critiques recur. First, tariffs are regressive, as they raise consumer prices disproportionately for lower-income households. Second, tariff revenue is volatile and can collapse if trade volumes reroute. Third, "fiscal dominance" implies that the Fed cannot cut interest rates when deficits are significant, regardless of what the Treasury does. The responses are design-specific. Pairing broad tariffs with a temporary, targeted offset—say, an expanded EITC funded from tariff proceeds—can neutralize regressivity while preserving the fiscal-liquidity channel. Volatility is absolute, but can be mitigated with rules: when tariff receipts exceed a quarterly threshold, Treasury automatically tilts issuance toward bills; if receipts undershoot, coupon calendars rise, and the Fed signals commensurate patience on cuts. As for dominance, market evidence suggests that long-end yields are increasingly driven by term premia rather than near-term inflation expectations; therefore, supply mechanics matter. A policy package that marries tariffs to issuance discipline and targeted relief does not require perfection; it requires consistency strong enough to bend the term premium without reigniting inflation.

Turn revenue into runway

The key statistic that should guide us over the next six months is not a CPI measurement; it is the portion of tariff revenue that leads to lost coupon issuance. The $30 billion collected in customs duties in July suggests fiscal potential that, if allocated to appropriate maturities, could reduce the term premium and create room for interest rate cuts, even as the Fed maintains its credibility. On the other hand, utilizing tariffs to finance permanent tax expenditures could keep long-term rates elevated, delay school construction, and strain district budgets due to the costs of financing rather than educational needs. The way forward can be easily articulated but is challenging to implement: commit, in writing, to a rule for issuing a consistent proportion of tariff revenues for bill issuance as quantitative tightening concludes; release the quarterly calculations alongside the refunding announcement; and align the initiative with targeted measures for lower-income families. If this is achieved, the fiscal-liquidity channel will enhance, rather than hinder, the effectiveness of monetary policy. If not, the term-premium trap will force policy rates to remain elevated for longer than inflation alone would necessitate. It is up to the Treasury to decide, while the Fed adjusts prices accordingly.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Al Jazeera (2025, Aug. 23). Is Trump's "Big Beautiful" spending law the biggest tax cut in U.S. history? (Explainer: ranking by GDP share).

Barron's (2025, Apr.). 'Term premium' sends a message: Inflation isn't what bond investors fear most.

Bipartisan Policy Center (2025, Feb. 4). Visualizing CBO's Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025.

Bureau of Economic Analysis (2025, Jul. 31). PCE Price Index—June 2025 release.

Cleveland Fed (2025). QT, Ample Reserves, and the Changing Fed Balance Sheet.

Congressional Budget Office (2025, Jan. 17). The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2025 to 2035.

Federal Reserve (2025, Jun. 20). Monetary Policy Report.

Federal Reserve (2025, Mar. 19 & Apr. 1). Policy normalization and runoff caps (QT taper to $5 bn Treasuries per month).

Federal Reserve (2025, Jul. 30). FOMC Minutes.

FRED, St. Louis Fed (accessed Aug. 2025). Overnight Reverse Repo usage (RRPONTSYD); Treasury General Account (WTREGEN).

Goldman Sachs Research (2025, Jul. 3). U.S. earnings will start to show the impact of Trump's tariffs (assumed ~70% pass-through).

MarketWatch (2025, Aug.). Markets are running low on extra cash (RRP near zero; liquidity concerns).

New York Fed (accessed Aug. 2025). Treasury term premia data.

Peterson Institute for International Economics (2025, Aug. 6). Tariff revenue tracker.

Politifact (2025, Aug. 22). Is the 2025 law the biggest tax cut? (ranking and methodology).

Reuters (2025, Aug. 26–27). Tariff-bolstered U.S. credit rating still tarnished; Bessent says tariff revenue could exceed $500 bn/year.

Scholarly survey—Greenwood, Hanson & Vayanos (2023/2024). Supply and Demand and the Term Structure of Interest Rates (NBER; Annual Review).

TBAC / U.S. Treasury (2025, Jul. 30). Quarterly Refunding documents and discussion of term premium.

U.S. Treasury (2025, Aug.). Quarterly borrowing commentary (PGPF summary).

VoxEU/CEPR (2025, Aug. 25). English, B. The Federal Reserve, the new administration, and the outlook for the economy and monetary policy.

Associated Press (2025, Jun. 4 & Jun. 17; Aug. 11). CBO: 2025 bill adds $2.4–$2.8 trillion to deficits; distributional effects.

Comment