Forge the Shield: Why ASEAN Needs a Union-Style Economic Defense Now

Input

Modified

ASEAN risks tens of billions in tariff costs under new U.S. measures Fragmented bargaining lets major powers play members against each other Build a union-style external economic system to negotiate as one

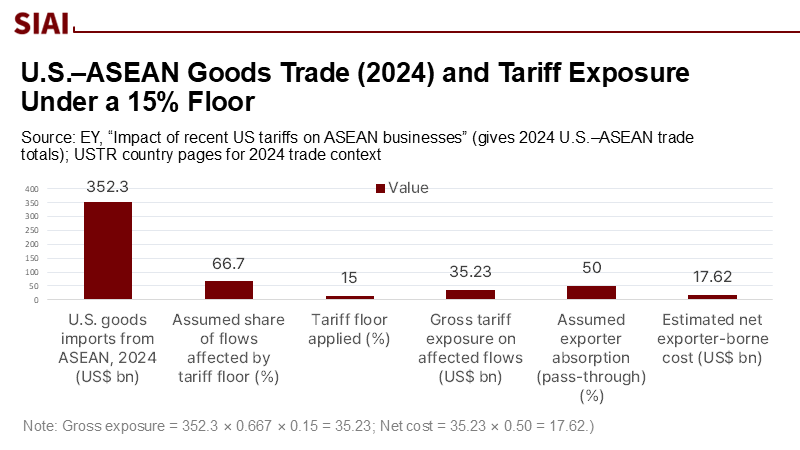

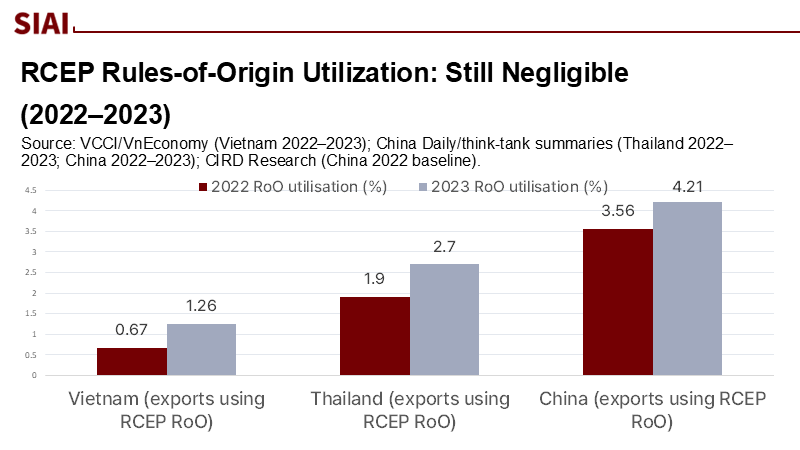

On August 7, 2025, the U.S. implemented a new "reciprocal" tariff framework, raising the minimum duty rate to 15 percent for most trade partners with which it has a trade deficit and eliminating the de minimis exemption for small shipments. In 2024, trade between the U.S. and ASEAN reached approximately $476 billion, potentially resulting in over $50 billion in tariff costs. Intra-ASEAN trade accounts for roughly 22 percent of total exports; however, early data indicate limited utilization of RCEP benefits, with only about 4 percent of Chinese exports and just over 1 percent of Vietnamese exports utilizing RCEP rules of origin in 2023. Fragmented negotiations and underutilized integration options could leave ASEAN economically vulnerable unless it adopts a more unified, union-style approach to its external economic relations.

From Liberalisation to Collective Defense

The prevailing prescription says "double down on regional liberalisation" to buffer external shocks. That is necessary but insufficient. Liberalisation without an external shield leaves ASEAN exposed to tariff whiplash and economic coercion from all directions, not just Washington. The U.S. tariff turn in August 2025—the 15 percent floor, country-specific surcharges, and collateral measures, such as the repeal of the de minimis threshold—illustrates how quickly market access assumptions can shift. Beijing's mix of inducements and penalties, and the uneven progress of U.S. IPEF trade rules, underscore a wider pattern: major powers are weaponising interdependence faster than ASEAN is building guardrails. The reframing is straightforward: shift from a trade-creation agenda within Asia to a bloc-level capability to defend market access, manage retaliation, and negotiate as one when an external actor imposes or credibly threatens economy-wide barriers. ASEAN's choice is not "openness or protection"; it is collective openness or serial vulnerability.

The Cost of Fragmentation, Quantified

Start with orders of magnitude. U.S. goods imports from ASEAN in 2024 were approximately US$352 billion; at a uniform 15 percent tariff, the gross exposure is approximately US$52.8 billion. Even if only two-thirds of flows are affected and exporters absorb half via price adjustments, the net first-round hit still approaches US$17–18 billion—more than the annual merchandise exports of several smaller ASEAN economies. Add logistical friction from the de minimis repeal and firm-level compliance costs, and the shock compounds. Concurrently, ASEAN's integration cushions are thinner than they appear: intra-ASEAN exports accounted for roughly 22 percent of total exports in 2023, and underutilization of RCEP preferences leaves money on the table every day. Low rules-of-origin uptake means firms continue to pay MFN rates when they could qualify for preferences—especially perishables in a world of sudden surcharges. Fragmented, country-by-country haggling with Washington (or Beijing) also dilutes leverage: what one capital concedes to defuse a tariff threat becomes the benchmark the next capital must beat. A union-style response is not symbolism; it is an actuarial imperative.

ASEAN's Missing Toolkit — and a Ready Template

ASEAN already has legal building blocks for flexible action: the Charter's Article 21(2) allows the "ASEAN Minus X" formula for implementing economic commitments when consensus exists to proceed—precisely the kind of flexibility needed to move quickly on external shocks. What ASEAN lacks is a codified external economic defense instrument—something akin to the European Union's Anti-Coercion Regulation, which establishes a graduated deterrent and response framework against economic coercion. The EU has not yet deployed the tool, but its existence has altered bargaining dynamics with major partners. ASEAN could adapt the concept to its institutional DNA, incorporating a rules-of-origin accelerator, solidarity backstops for targeted sectors, and automatic triggers for joint negotiation whenever an external tariff or quota breaches a pre-agreed threshold. Pair these with the operational bodies already forming under the IPEF Supply Chain Agreement—such as data sharing, stress testing, and crisis response—and the region would transition from ad hoc communiqués to predictable, deterrent power.

Build the Union-Style External Economic System

Here is a practical architecture that fits ASEAN's norms but delivers hard power at the border. First, create an ASEAN Joint Negotiating Team (AJNT) mandated to bargain as one with any partner imposing economy-wide measures, activated by a clear threshold (e.g., an across-the-board tariff ≥ 10 percent or any measure covering ≥ 15 percent of ASEAN exports by value). Second, legislate an ASEAN External Action Protocol that pre-commits members to an everyday counter-offer schedule—tariff-rate quotas, phased suspensions, and services-market concessions—so individual capitals cannot be played off against each other. Third, establish an ASEAN Tariff Compensation Facility (ATCF) capitalized by a small levy on preferential-rate import clearances and co-financed by ADB/AMRO partners, providing time-limited adjustment support to sectors demonstrably affected by third-country surcharges. Fourth, launch a Rules-of-Origin (RoO) Accelerator to push RCEP/CPTPP utilisation to ≥ 20 percent within two years via pooled certification services, digitised origin data, and shared auditors; even moving from 1–4 percent utilisation to 15–20 percent unlocks billions in foregone preferences.

This system is not theoretical. The Charter permits the implementation of 'Minus X' in economics; ASEAN can define the AJNT and Protocol as the implementation of existing community trade objectives. The key to success lies in collective action. If a partner wants a special deal with Vietnam, Thailand, or Malaysia, it should face the AJNT's single regional counterparty—not a menu of bilaterals.

Governance Without Brussels — Using ASEAN Minus X

The objection that "ASEAN is not the EU" is both accurate and beside the point. A union-style external economic tool need not replicate the supranationalism of the European Union. It can be anchored in ASEAN's intergovernmental DNA through pre-delegated mandates and the activation of Minus X. The Protocol can specify that once a super-majority of GDP or trade (say, 70 percent) endorses AJNT activation, the common counter-offer binds participating members; others can accede later on the same terms. The dispute-settlement architecture of the ASEAN Economic Community, along with the Charter's own references to rules-based settlement, provides legal cover.

Meanwhile, finance ministries can hardwire national budgeting processes to provision the ATCF based on transparent exposure formulas. Crucially, the Protocol should require that any bilateral concession offered during a tariff crisis be notified to AJNT and become the collective reserve price—eliminating the incentive for major powers to shop among ASEAN capitals for the lowest offer. This is sovereignty exercised together, not surrendered.

What Skeptics Get Wrong—and How to De-Risk the Plan

Skeptics argue that collective action invites retaliation. In reality, fragmented appeasement raises the price of peace; collective clarity can shorten disputes. The August 2025 tariff wave highlights the asymmetry: Japan and Korea negotiated bespoke terms; India was hit with steep increases; South Korea, however, saw a negotiated rate still locked in at 15 percent. ASEAN will fare worse if it bargains piecemeal. Another critique claims that bloc-level defense violates WTO disciplines. It does not. Everything proposed—joint bargaining, counter-offers, time-limited compensation, RoO acceleration—fits within WTO-consistent instruments. A final critique suggests that small economies will be pulled down by the large—the ATCF's exposure-based formula and the AJNT's super-majority trigger, rather than unanimity, address this. The real risks sit on the other side: without a union-style system, supply chains will drift to whichever ASEAN member scores a bilateral fix, tariffs will arbitrage away regional preference schemes, and the region's negotiating chip will continue to shrink precisely when de-risking and "China-plus-one" dynamics could have favoured a cohesive ASEAN.

From Blueprint to Deployment—Six Moves in 180 Days

Set a deadline and sequence. Within 30 days, finance and trade ministers should approve the External Action Protocol text in principle and begin establishing the AJNT, with secondees from each capital. By day 60, customs heads should publish the RoO Accelerator work plan—single-window origin data, pooled certification, and a joint audit roster—and outline national legal adjustments for electronic certificates across RCEP/CPTPP members. By day 90, ministers should capitalise the ATCF with a small levy on preferential clearances and a credit line from regional development partners. By day 120, the AJNT should circulate a collective offer schedule calibrated to current U.S. measures (and any Chinese countermeasures), with fallback options that maintain ASEAN's overall openness intact. By day 180, ASEAN should run a live stress drill using current tariff settings, publish the region-wide exposure map, and commit to automatic AJNT activation thresholds. This is not maximalism; it is institutionalising what ASEAN already does ad hoc, fast enough to matter in markets.

The Single Statistic, Revisited

Return to the initial figure: a potential gross tariff exposure exceeding US$50 billion, layered upon a US$3.8 trillion trade ecosystem, where approximately only one out of five export dollars remains within ASEAN and where companies are not fully utilizing the preferences intended to mitigate shocks. No amount of rhetorical "centrality" alters these figures; only collective action can make a difference. An external economic system akin to a union—such as AJNT, Protocol, ATCF, and RoO Accelerator—does not necessitate a Brussels in Jakarta. It requires the political determination to transform ASEAN's flexibility into a leverage and its integration into a protective barrier. Trade liberalization within Asia is crucial, but ASEAN must also grasp the most contemporary lesson of interdependence: that openness must be defended. If the region can maneuver within 180 days, it can dictate the terms of access for 680 million consumers, rather than allowing Washington or Beijing to do so. If it fails to act, the tariff shock of 2025 will set the precedent for future occurrences, each time demanding a greater cost for the opportunity to sell to markets that ASEAN can and should collectively engage with.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Asia Foundation. Critical Issues for the United States in Southeast Asia in 2025. October 2024.

Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. "Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (Supply Chain Agreement)." Accessed 2025.

East Asia Forum. "Asia must double down on regional trade liberalisation to overcome the cost of Trump's trade chaos." August 25 2025.

European Parliament Research Service. "EU Anti-Coercion Instrument — legislative briefing." 2023.

J.P. Morgan Global Research. "US Tariffs: What's the Impact?" August 11 2025.

Ministry of Trade and Industry, Singapore. "CPTPP — Members and status." Updated 2024.

United States Congress (CRS). "Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) — In Focus (IF12373)." July 22 2024.

United States Trade Representative. "Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)." 2025 update (data for 2024).

U.S. White House. "Further Modifying the Reciprocal Tariff Rates." Executive action page, July 31, 2025.

AP News. "A U.S. tariff exemption for small orders ends Friday." August 27 2025.

ASEAN Secretariat. ASEAN Statistical Highlights 2024 (ASH-2024). 2024.

ASEAN Secretariat. ASEAN Statistical Yearbook 2023. 2023.

ASEANstats Data Portal. Key Indicators (trade and FDI). Last updated 2025.

ASEAN Charter (official text). Article 21(2).

Crowell & Moring. "The Anti-Coercion Instrument: What is it and how Europe might use it." Client note, February 4, 2025.

ERIA. "How Preferential are RCEP Tariffs?" Discussion Paper, 2022.

Reformdata/CIRD. "Unleash RCEP's Dividends by Focusing on Raising the Utilization of Rules of Origin." May 2025.

VnEconomy. "Utilisation rates of trade benefits from RCEP remains modest." December 13 2024.

Reuters. "Trump issues blitz of tariff announcements…" July 30 2025.

Reuters. "South Korea export growth seen slowing on higher U.S. tariffs." August 27 2025.

Reuters. "India hit by U.S. doubling of tariffs, plans to cushion blow." August 27 2025.

Van Der Consulting. "U.S. Shifts, China Pauses: ASEAN Caught Between Opportunity and Uncertainty." August 25 2025.

WilmerHale. "The EU Anti-Coercion Regulation: A New Tool Against Economic Pressure." April 2, 2025.

Comment