Automation-First Reshoring: Paving the Way for Growth and Success by Making Labor Costs Vanish

Input

Modified

Reshoring works only when automation slashes unit labor costs Raise robot density and software-driven productivity, not tariffs Tie incentives to verified plant gains and workforce upskilling

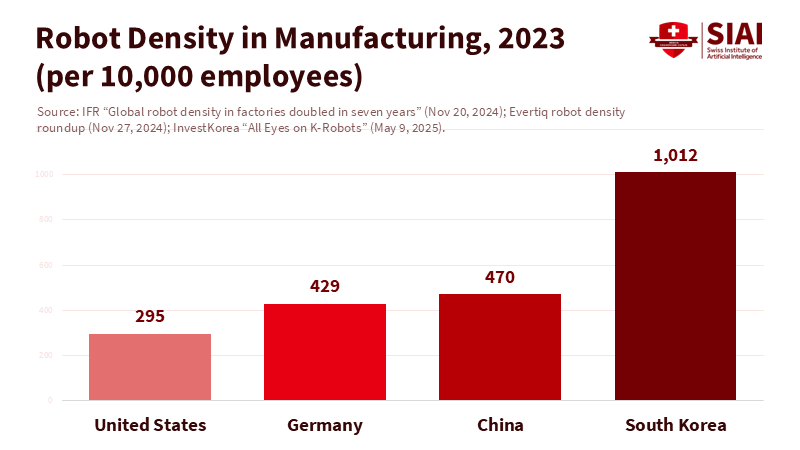

One key point that should change the reshoring debate is that, in 2023, U.S. factories had 295 industrial robots for every 10,000 manufacturing workers. In contrast, China had 470 and Germany had 429. This gap is tangible and measurable. It reflects the difference between unit labor costs that keep production overseas and a domestic cost structure that makes “Made in America” competitive without ongoing subsidies. In the past two years, America has invested heavily in new factories. Manufacturing and construction have roughly doubled since late 2021. However, manufacturing unit labor costs still rose 3.3 percent in 2024 and another 2.0 percent year-on-year by mid-2025. Building new factories alone doesn’t reshore production; automation does. Without a significant and measurable increase in robot density and productivity, tariffs and opening ceremonies will provide less output than expected. The key to sustainable reshoring lies in significantly reducing the labor portion of the domestic cost equation by increasing productivity through capital investment.

Why Automation, Not Tariffs, is the Key to Successful Reshoring

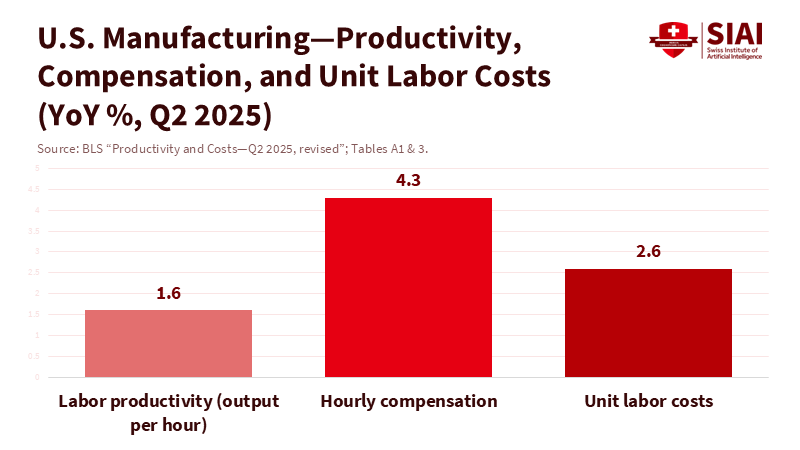

The political push to tax imports views reshoring as a trade policy issue. However, the deciding factor for a factory's location is actually a unit cost issue. BLS defines unit labor costs as hourly compensation divided by labor productivity; changing the productivity figure significantly alters reshoring calculations, even if nominal wages remain high. In simpler terms, unit labor costs represent the amount of labor required to produce one unit of output. Throughout 2024, manufacturing unit labor costs increased by 3.3 percent because compensation grew faster than modest productivity gains. By the second quarter of 2025, productivity gains improved to 1.6 percent, but still not enough to quickly influence location decisions. This is why merely increasing import barriers could lead to higher capital expenditure prices and slower equipment upgrades. Tariffs have already raised costs for crucial machine tools and components, causing U.S. manufacturers to pay more for Chinese machinery that they still rely on directly or indirectly through imports from third countries. Penalizing components without reducing labor intensity through automation will keep costs high and restrict capacity.

The last five years have demonstrated how supply-chain risks have prompted companies to reduce distances and increase inventory levels. However, the economics of near-shoring or reshoring depend on output per worker. A recent model of U.S. import logistics estimated that foreign delivery delays were extended by about 21 days from 2018 to 2024, raising inventory-to-sales ratios and causing a measurable reduction in output, as well as higher prices. Domestic production becomes more appealing only if unit costs can compete with offshore options. This is where industrial automation plays a crucial role: it converts wage differences into one-time capital expenditures, plus ongoing operating and maintenance costs, thereby reducing the labor share in each output unit. Global evidence supports this idea: robot adoption has added roughly 0.36 percentage points to annual labor productivity growth in advanced economies, with the global stock of operating robots surpassing 4.28 million in 2023. In simple terms, countries excelling in automation are also excelling in reshoring.

American companies are not starting from scratch. Robot orders in North America stabilized and began to recover through late 2024 and into 2025 after a temporary decline, with food and consumer goods leading the way. However, the key benchmark isn't just an increase in orders; it is robot density and overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) in U.S. plants compared to international competitors. With China at 470 robots per 10,000 workers and Korea exceeding 1,000, U.S. robot density is still a disadvantage in many sectors, beyond just automotive and electronics. Until U.S. robot density and software-defined automation significantly improve unit labor costs, the discussion about large-scale reshoring will continue to outpace measurable outcomes.

What “Affordable” Means: The Productivity Math

Reshoring's success hinges on a straightforward relationship: ULC = W / P, where W is hourly compensation and P is output per hour. Policy may adjust W slightly, but the only scalable lever is P. The question is: how much increase in P is necessary? Just look at recent BLS data. From 2023 to 2024, manufacturing productivity rose by only 0.6 percent while compensation increased by about 4 percent. By 2025 (up to Q2), productivity finally rose to 1.6 percent over the previous four quarters. At this rate, closing a 15–25 percent unit cost gap with highly automated competitors would take too long to affect current investment cycles. McKinsey’s research suggests that widespread automation, including AI systems, can add 0.5 to 3.4 percentage points to yearly productivity growth. The historical contribution from robots alone sits at around 0.36 p.p. A realistic goal for “automation-first reshoring” is to achieve 1.5–2.0 p.p. of sustained annual productivity improvement over five years in sectors considered for reshoring, such as electronics assembly, precision components, particular food and consumer goods, and chemicals. This would bring cumulative P-gains above 8–10 percent. Such a shift would visibly lower ULC. When combined with savings in logistics and decreased risks, this could shift the net present value in favor of U.S. locations, even with higher W. These targets assume continuous line balancing, increased OEE through vision-guided robotics, and software orchestration that reduces changeover times by 20–40 percent, which top adopters already achieve.

Critics may argue that robot orders fell in 2023, and some sectors delayed purchases in 2024 due to higher interest rates. That cyclical signal is valid, as the Wall Street Journal indicated a slowdown after the surge following the pandemic. However, forward indicators are more critical for location decisions than a single year's order numbers. A3 data show a steady market in 2024 and a slight increase in the first half of 2025. According to IFR, while Asia continues to lead in new installations, the Americas are not stagnant. Additionally, the capital investment supporting reshoring, including CHIPS and Science Act grants, investment tax credits, and the Inflation Reduction Act’s Section 45X manufacturing credits, has already sparked an unprecedented wave of U.S. manufacturing construction, particularly in electronics. This construction represents sunk costs; what drives usage and price per unit is how aggressively firms automate the lines they are building.

The trade policy's price signals are also inconsistent. Kearney’s 2024 Reshoring Index indicated a genuine shift away from China and toward North American suppliers. Still, the 2025 edition turned negative: U.S. manufacturing import ratios increased even as CEO intentions to reshore rose. This gap highlights the core thesis: intent without productivity remains just marketing. Simultaneously, new studies on shipping and inventory confirm that delivery delays and added risks encourage firms to shorten supply lines. Still, these do not guarantee domestic production unless unit costs drop. An “automation-first” perspective views tariffs as temporary accelerants at best; the long-lasting margin comes from reducing the labor share per unit through investments in capital and software.

From Policy to Plant Floor: A Playbook

Turning slogans into real siting requires a practical playbook across four areas: equipment, software, workforce, and institutions. Regarding equipment, the goal isn’t just to “buy robots.” It is to densify automation where costs matter most: in pick-and-place, palletizing, inspection, and repetitive assembly. North American orders in late 2024 leaned towards food and consumer goods, where moderate-complexity, high-volume tasks can yield quick OEE improvements. “Robots-as-a-Service” models lower the barrier for small and mid-sized manufacturers by converting capital expenditures into operating expenses. The East Asia Forum’s analysis highlights RaaS as a means of spreading automation to non-leaders. Since tariffs have increased the cost of some imported machine tools, public procurement could offset this by subsidizing domestic automation content through performance-based credits tied to realized productivity, rather than just purchases. A helpful method would tie credits to independently verified OEE and scrap-rate improvements, rather than just invoice totals.

Software is where the next wave of productivity gains will come from. Vision systems, digital twins, and AI-supported scheduling enhance returns on hardware. Both IFR and OECD indicate that integrating AI with robotics is at the leading edge, with global robot stocks and density at record levels. However, the significant advancements increasingly stem from software-defined automation—quick reprogramming, testing in simulations, and predictive maintenance. Federal support should focus on creating open, vendor-neutral interfaces and testbeds, allowing integrators to combine components without needing specialized code. Manufacturing USA institutes—like the ARM Institute and CESMII—already function this way; their 2024–2025 impact reports indicate growing networks of firms and training partners. A simple procurement rule, like “prefer standards-compliant cells,” would hasten diffusion and reduce overall costs.

Workforce policy must break away from an outdated binary: it is not about “cheap labor vs. no labor.” Automation reduces the number of routine workers needed, but it also raises the skills required. The Manufacturing Institute and Deloitte estimate that the U.S. will need 3.8 million manufacturing workers between 2024 and 2033, with about half potentially unfilled without targeted training. NIST’s Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) network reported over 108,000 jobs created or retained in FY2024 through modernization projects. Its value isn’t in sheer volume training; it lies in connecting small and mid-sized firms with integrators. This network, along with apprenticeship programs and certification bodies like SACA, should receive support and be expanded because it turns automation spending into practical capabilities on the production line. The right goal is not simply “more workers” but “more productive workers” alongside machines.

Institutions are crucial because reshoring is a systemic issue. The Clean Investment Monitor shows that manufacturing is the fastest-growing part of clean-energy investment since the IRA, with electronics playing a significant role in the building boom. CHIPS and Science have provided grants and incentives that bring advanced fabs and packaging back to the U.S. These policies are necessary but not enough. To convert construction into competitive output, agencies should (a) link grants to automation goals (like robot density, first-pass yield, and changeover times), (b) make some credits contingent on workforce certifications relevant to specific roles (rather than generic “digital skills”), and (c) expand co-funded test cells in community colleges where integrators can demonstrate ROI with small and mid-sized enterprises before making purchases. Done effectively, this institutional support can transform temporary funding boosts into lasting cost reductions.

The public conversation will continue to focus on jobs. Recent data indicate that manufacturing employment has slowed in 2025 and that the BLS’s annual revision has lowered reported job gains. This does not challenge the idea of automation-first reshoring; it serves as a reminder that job counts are not a great measure of competitiveness. The reshoring strategy should aim to increase value-added per worker and reconfigure jobs to focus on higher-skill positions, such as maintenance, programming, quality control, and logistics, that work in conjunction with automation. The policy framework we should pursue is clear: we are trading some routine tasks for more stable, higher-paying roles in plants that can withstand economic fluctuations and geopolitical stresses because their unit costs remain competitive globally. If we neglect automation, we risk developing an industrial base that employs more people but may not survive the next economic downturn. These layers together form a practical roadmap for automation-first reshoring.

The U.S. has 295 robots per 10,000 workers, compared to 470 in China. This represents the cost gap in physical terms. The increase in factory construction indicates that capital is available; however, the changes in unit labor costs and fluctuations in manufacturing jobs suggest that productivity remains lacking. Our call to action is clear: set a national goal to close half the robot-density gap with China by 2028 in sectors suitable for reshoring. We need to link federal manufacturing incentives to measurable improvements in unit labor costs and first-pass yield. We should incorporate RaaS and open interfaces to help small and medium-sized enterprises join in. Additionally, fund community college test cells and certifications to make automation standard practice rather than custom work. If we succeed in this, “Made in America” will be about numbers, not feelings; it will create a domestic cost curve that competes independently, without ongoing protection. If we fail, the factories we build today will remain under-automated structures tomorrow, vulnerable to the next economic downturn and price war. Reshoring is possible, but we must automate first and discuss tariffs later.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). (2024, Mar. 7). Productivity and costs – technical note and definitions.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). (2025, Sept.). Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) – July 2025.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). (2025, Sept.). Productivity and costs: Second quarter 2025, revised.

Clean Investment Monitor (Rhodium Group & MIT CEEPR). (2024, Aug. 7). Tallying the two-year impact of the Inflation Reduction Act.

East Asia Forum. (2025, Sept. 10). Reprogramming trade in Asia for an automated future.

International Federation of Robotics (IFR). (2024, Sept. 24). Record of 4 million robots in factories worldwide.

International Federation of Robotics (IFR). (2024, Nov. 20). Global robot density in factories doubled in seven years.

Kearney. (2025, Apr. 30). 2025 Reshoring Index: The great reality check (press release).

Manufacturing USA – ARM Institute. (2025, Jun. 26). ARM Institute issues 2024 impact report.

Manufacturing USA – Workforce Development (n.d.). Key initiatives.

Manufacturing Dive. (2025, July 8). Tariffs or not, automation is still key to reshoring manufacturing.

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) – MEP. (2025, Mar. 20). MEP economic impacts boost business and jobs.

OECD. (2025, June 23). Emerging divides in the transition to artificial intelligence.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2025, Sept. 2). Monthly construction spending – July 2025.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2023, June 27). Unpacking the boom in U.S. construction of manufacturing facilities.

Washington Post. (2025, Apr. 27). Tariffs on Chinese-made machinery drive up costs for U.S. manufacturers.

Comment