Swap Tariffs for Talent: The Only India, U.S. Trade That Delivers

Input

Modified

Put talent—not tariffs—at the center of the India–U.S. deal U.S. factories need skilled workers now; India can supply them through stable visa pathways Tie mobility to wage floors, apprenticeships, and strict compliance so both economies win

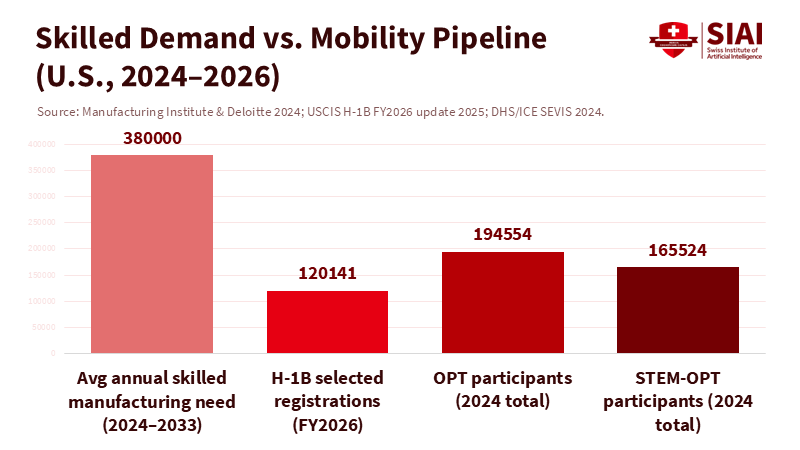

The number to focus on is 331,602. This marks the number of Indian students who came to study in the United States for the 2023-24 academic year, a record high that makes India the top sender for the first time since 2009. They are not just sources of tuition revenue. A significant number move into Optional Practical Training, graduate into high-demand technical jobs, and help keep the innovation economy thriving in labs, hospitals, data centers, and—if America's re-industrialization is to succeed—in battery and semiconductor plants. However, the policies surrounding them do not match the scale of the need. In July 2025, the United States still had 7.2 million job openings, while the H-1B system selected just about 120,000 registrations for FY2026 under a new, cleaner process focused on beneficiaries. If Washington wants to build more at home, why negotiate trade with a country that produces perhaps the world's largest pool of young engineers while sending mixed signals about welcoming them? This is a self-imposed problem—and it can be fixed, but the time to act is now.

We continue to treat labor mobility as a minor issue. It should be central to the discussion. India's view is clear: it can accept tougher market access for goods temporarily if it can send talent to higher-productivity environments. The United States should find this even simpler: it cannot run the factories it is subsidizing without a surge of skilled workers, many of whom will initially come from abroad while domestic supply develops. Combine these truths, and a workable deal appears—one that exchanges immediate goods access for medium-term, rules-based, high-skilled mobility that meets America's industrial needs and India's surplus of talent. The other option is already visible: tariffs that reduce certainty and investment, along with enforcement actions that remove the very technicians needed to get projects running. An agreement that includes mobility in the text—rather than relegating it to side discussions affected by domestic politics—would better match policy with reality.

The trade we keep missing

Plants do not run on subsidies; they run on people. Independent analyses indicate that U.S. manufacturers will need about 3.8 million additional workers between 2024 and 2033. Roughly half of those positions risk remaining unfilled if current supply chains do not expand. Even as the general labor market cools, local skill shortages are immediate and pressing: project ramp-ups are delayed, costs rise, and safety risks increase as inexperienced teams are stretched thin. Policymakers have started investing in training—there were about 680,000 active participants in registered apprenticeships in FY2024, and CHIPS-funded workforce programs continue to grow—yet the gap between annual needs and annual graduates remains wide. Mobility does not replace domestic training; it connects domestic training to the investment wave already underway.

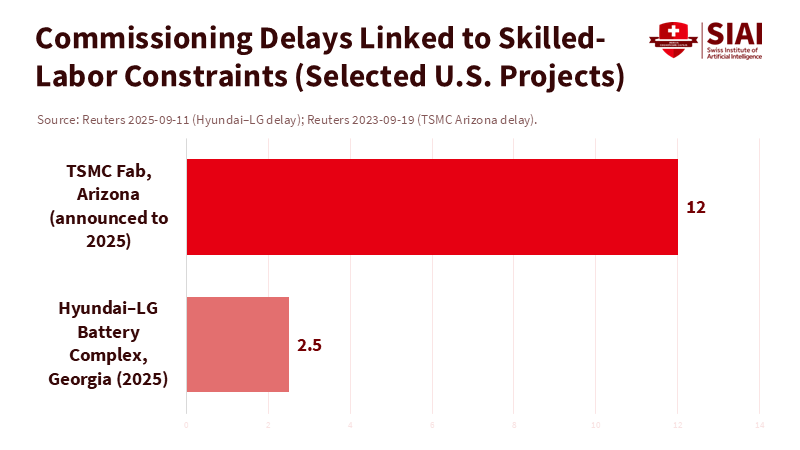

Recent events have made the stakes painfully clear. In Georgia, a massive Korean-U.S. battery plant is delayed by two to three months after a significant immigration enforcement action removed hundreds of skilled technicians, many of whom are foreign workers, who were essential for suppliers to install and validate equipment. Company leaders stated that the problem was not just in numbers; it was in the specialized knowledge that is rare in the U.S. In Arizona, TSMC's first fab has already been pushed to 2025 due to a lack of skilled workers. Suppose policy forces companies to build while making it hard to import expertise needed to launch and stabilize production. In that case, the results will be predictable: delays, cost overruns, and fewer jobs created. A structured system that allows vetted engineers and technologists—mainly from India—to fill these gaps, along with significant investments in U.S. apprenticeship programs and community colleges, would lower project risks and enable industrial policy to deliver on time.

A demand shock for skills—and a supply India can deliver

Look at the upstream pipeline. Open Doors reports 331,602 Indian students in U.S. higher education for 2023-24, showing robust growth at the graduate level and nearly 98,000 at the OPT stage. This is not just a trickle; it is a vast source of early-career talent trained on U.S. campuses, already vetted through immigration and security checks. Yet the transition from OPT to long-term status is where the system gets stuck. For FY2026, USCIS selected about 120,000 H-1B registrations; integrity improvements have made the process fairer, but the cap is far below demand. On the permanent side, employer-sponsored green card processing has reached an average of 3.4 years as of mid-2025—an all-time high—leaving many potential hires in limbo. The contradiction is striking: universities and businesses are increasing skill supply, but policy limitations throttle it.

Now consider India's situation. The country is the world's largest recipient of remittances—around $125 billion in 2023—and its services exports are still growing. On energy, India has benefited by buying discounted Russian oil; reliable sources show Russian crude making up a significant portion of its imports in various periods from 2024 to 2025. Washington's tariff response—now raising some Indian export duties to 50 percent—strengthens New Delhi's motivation. If tariffs limit access to goods, the outcome that India desires most in a trade reset is clear: stable and reliable pathways for its skilled workers to live, train, and start businesses in the U.S. In a mobility-first deal, India can accept temporary pain on goods if it secures clear gains for people.

This is not one-sided generosity; it is mutual benefit. Consider a conservative estimate. Suppose a talent chapter adds 50,000 additional Indian STEM workers each year for three years through a mix of expanded cap-exempt visas linked to accredited groups, streamlined short-term entry processes, and a clear pathway from OPT to green card in fields like microelectronics, power systems, advanced manufacturing, and health technology. If average pay is about $120,000 and even 10 percent is sent home, this could yield around $600 million a year in added remittances—small compared to India's total, but politically crucial for families. For the U.S., these 50,000 workers would go where bottlenecks are most significant: facilities that need technicians who can work with complex equipment, while American apprentices develop the same skills. The goal of a trade agreement is not just about tariff lines; it is about aligning incentives so that the right people show up where the economy needs them most, paving the way for a brighter future for both countries.

Designing a mobility-for-industrial strategy

The mechanics are neither new nor radical. First, supplement the cap-limited H-1B with a targeted, time-limited "Industrial Skills Quota" set aside for groups in semiconductors, batteries, grid modernization, and biomanufacturing. Selection should follow the beneficiary-centric rules now in place, with wage standards and mandatory training benefits for U.S. community colleges. Second, stabilize the student-to-worker path. OPT and STEM-OPT have become de facto pipelines; however, their status is uncertain, and they are under regulatory challenge. Cementing their reliability within a trade chapter—combined with stronger employer compliance and a clear road to permanent residency for graduates in high-need areas—would reduce uncertainty and opportunistic lawsuits. Third, exceptions for specialized foreign workers should be apparent. When a new manufacturing plant or gigafactory opens, companies should have guaranteed, short-term access to skilled foreign technicians for installation, qualification, and training, with a firm deadline and a requirement to train local workers. This avoids the false dilemma of "importing labor forever" versus "delaying projects because local knowledge hasn't developed yet."

Fourth, tie visas to qualifications. The U.S. already spends public funds to expand the semiconductor workforce; updates to the CHIPS program show an investment of hundreds of millions, both from state and private sources, in training. Use the trade agreement to connect those programs to Indian technical schools: joint course offerings, shared laboratories, and dual-campus apprenticeships that count toward licensure on both sides. The registered apprenticeship system is the proper foundation. With roughly 680,000 active participants and evidence of growth into new sectors, it can expand to larger groups if the industry provides paid placements and the necessary equipment. A mobility-first chapter gives companies a strong reason to co-invest: access to the foreign engineers they need today in exchange for real progress in domestic training for tomorrow.

Finally, address politics head-on. American voters have mixed views on immigration overall. Still, when asked about priorities, many say that high-skilled workers should be prioritized, and general concerns about immigration have decreased since last year. This consensus is fragile; a mobility-first agreement will struggle if seen as an elite privilege. The solution is to frame it accurately as part of a broader plan to boost productivity, lower supply chain risks, and create middle-class jobs in areas that missed the last tech boom. In practice, this means connecting mobility to local benefits, including guaranteed apprenticeship positions, funding for equipment at public colleges, clear workplace safety standards, and penalties for companies that fail to meet their training commitments. It also requires faster, more predictable processing—waiting around 3.4 years for employer-sponsored green cards is unacceptable in a so-called "build here" era. Fix the system, and the politics will follow.

The 331,602 Indian students are not just numbers, they are the human foundation of a relationship that is often reduced to tariff disputes and photo opportunities. Many already work in American labs and companies under limited authorization, only to wait for years in queues disconnected from the urgency of the factories we need to get running. Meanwhile, manufacturers warn of millions of empty jobs this decade, and key projects are delayed because the people who can get them started are elsewhere. An agreement that exchanges immediate goods concessions for long-term, rules-based mobility would align the deal with the actual economy: it would place the right skills where they are needed as U.S. training programs expand, and it would provide India with what it values most—opportunity for its talented people—without requiring Washington to compromise on security or enforcement. The measure of success is simple. If, a year after the deal, more American factories are operating at full capacity and more Indian engineers are filling the most challenging jobs—while apprenticeships and community colleges reach record placement rates in those same facilities—then the agreement is successful. This is the mobility-first vision worth pursuing.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Atlantic, The. (2025). Just How Bad Would an AI Bubble Be? Retrieved September 2025.

CEPR VoxEU. Eisfeldt, A. L., Schubert, G., & Zhang, M. B. (2023). Generative AI and firm valuation (VoxEU column).

EDUCAUSE. (2025). 2025 EDUCAUSE AI Landscape Study: Introduction and Key Findings.

EdScoop. (2025). Higher education is warming up to AI, new survey shows. (Reporting 57% of leaders view AI as a strategic priority.)

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2025). AI is set to drive surging electricity demand from data centres… (News release and Energy & AI report).

Macrotrends. (2025). NVIDIA PE Ratio (NVDA).

McKinsey & Company. (2023). The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier.

McKinsey & Company (QuantumBlack). (2025). The State of AI: How organizations are rewiring to capture value (survey report).

METR (Model Evaluation & Threat Research). Becker, J., et al. (2025). Measuring the Impact of Early-2025 AI on Experienced Open-Source Developer Productivity (arXiv preprint & summary).

MIT Media Lab, Project NANDA. (2025). The GenAI Divide: State of AI in Business 2025 (preliminary report) and Fortune coverage.

Reuters. (2025). Alphabet raises 2025 capital spending target to about $85 billion; U.S. data centre build hits record as AI demand surges.

U.S. Department of Energy / EPRI. (2024–2025). Data centre energy use outlooks and U.S. demand trends (DOE LBNL report; DOE/EPRI brief).

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). (2025). Short-Term Energy Outlook; Today in Energy: Electricity consumption to reach record highs.

UBS Global Wealth Management. (2025). Are we facing an AI bubble? (market note).

Meta Platforms, Investor Relations. (2025). Q1 and Q2 2025 results; 2025 capex guidance $66–72B.

Alphabet (Google) Investor Relations. (2025). Q1 & Q2 2025 earnings calls noting capex levels.

Bakhtiar, T. (2023). Network effects and store-of-value features in the cryptocurrency market

Comment