Visas for Investment: Urgent Measures Needed to Address the U.S.-Korea Rift

Input

Modified

A shortage of skilled labor hinders U.S. reindustrialization A U.S.–Korea deal should trade investment and tariff relief for targeted, time-limited visas This compact speeds factory rollouts now and builds durable American training pipelines

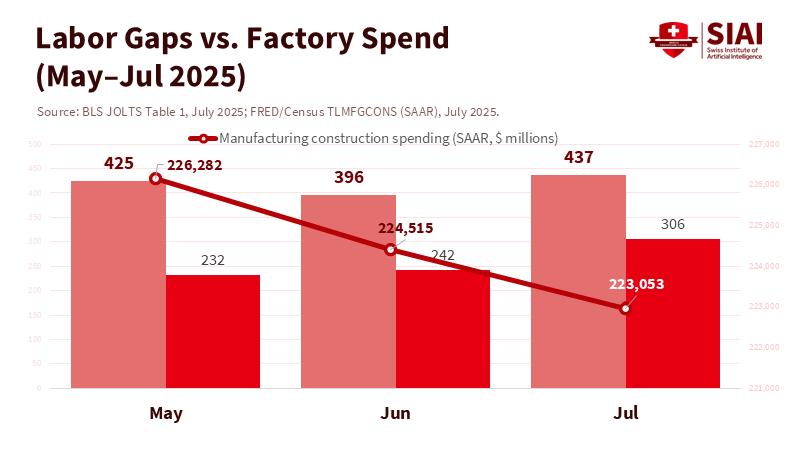

To rebuild factories at the rate politicians promise, the United States must address a fundamental math problem. In July 2025, there were 437,000 open manufacturing jobs, even before the new fabs, auto plants, and battery lines start operating. This number is significant when paired with another key figure: U.S. manufacturing construction spending is about $223 billion (SAAR), close to historical highs. This is primarily driven by semiconductor and clean-tech investments that will falter without enough skilled workers to install and operate them. To be blunt, tariffs and investment pledges shuffle money; visas allow for the flow of knowledge, and that knowledge is what makes a difference. The immigration raid that sent hundreds of South Korean technicians back home from a Georgia battery site delayed the startup by months. This was not just about enforcement; it highlighted a key limitation in America’s industrial policy. Any U.S.-Korea agreement that does not trade market access and capital for skilled labor will fail to meet its own goals.

Bureau of Labor Statistics

From Tariffs to Talent: Reframing What’s Actually Scarce

The standard view frames U.S.-Korea tensions as a tariff battle, but this perspective is misguided. Since the KORUS FTA came into effect in 2012, tariffs on most industrial and consumer goods have dropped to zero in five to ten years. By 2016, nearly all bilateral industrial trade was duty-free. This period of almost seamless goods trade allowed Korea’s global leaders to sell in America as though they were domestic. At the same time, U.S. producers enjoyed reciprocal access and compliance with non-tariff barriers. Now, we are negotiating in a different environment, defined by post-pandemic supply-chain politics and rising unilateral tariffs. The legal uncertainty about how far a president can stretch emergency trade powers further complicates matters. If tariffs are the surface issue, labor is the core issue. The real question is not whether to tax a product at 0, 15, or 25 percent. It’s whether we can muster enough technicians, engineers, and line operators to manufacture the product here at all.

U.S. job data reinforces this narrative. Manufacturing employers have posted between 400,000 and 500,000 vacancies over the past two years. Construction roles, which are crucial for these new plants, had around 306,000 openings in July. Industry surveys show that most firms have trouble hiring qualified labor. Semiconductor groups forecast many thousands of unfilled jobs by the end of the decade, even with a domestic training surge. These are not temporary issues you can fix with slogans; they are deep-rooted gaps in the skills pipeline. If we insist on building fabs and gigafactories quickly, we will need skilled foreign specialists to install equipment and train American teams, at least during the initial phases. Without this, taxpayer-supported mega-projects risk becoming stranded assets, waiting on a workforce that never materializes.

Chaebols’ Market Access Is Fading—Leverage It Into Skills Pipelines

For nearly a decade after KORUS took effect, Korea’s conglomerates enjoyed what critics termed a “honey spot.” They could export into the world’s richest consumer market at very low tariff rates, and increasingly invest within it. That period is over. The White House’s tariff adjustments—first raising baseline rates, then instituting country-specific rates—have put Seoul on the defensive. They are negotiating a package reportedly built around a $350 billion U.S. investment pledge and a reduced 15 percent tariff rate, still above the zero rate both economies had gotten used to. The outline of this deal exists on paper, but the political details remain unresolved. Even as leaders celebrated “agreements in principle” this summer, negotiators admitted there are significant outstanding issues, from agriculture to foreign-exchange challenges. In this situation, Seoul’s leverage is not just financial; it includes the speed and sophistication of the production Korea can establish on American soil—if the U.S. allows in the necessary personnel.

The raid on a Georgia battery project made this leverage evident. Nearly 300 South Korean specialists, the kind needed to bring a new plant to life, were detained and sent back home. Hyundai now estimates at least a two to three-month delay. The South Korean president responded on September 11 by publicly warning that without a reliable visa route for skilled Korean workers, companies will hesitate to expand in the U.S. If Washington wants the jobs and capacity—and it does—it should take this warning seriously as a call for policy action. Consistent enforcement is critical, as is a legal pathway for temporary technical work that currently falls through the gaps between business visitor rules, H-1B backlogs, and seasonal H-2B limits that don’t fit advanced manufacturing.

There is also a critical higher-education element that current negotiations ignore at their own risk. Korea is still a top source of international students in the U.S., with 43,149 enrolled in 2023/24. These engineers and data scientists could feed CHIPS-era employers through various training programs, if the door they enter as students connects to a door they can exit into employment. If we disconnect these pathways, we will continue training the world’s talent, only to have them leave to build factories elsewhere. A rethink of trade that prioritizes students and apprenticeships would better align tariffs, investments, and skills, rather than allowing each to operate independently of the others.

A Visas-for-Investment Compact That Actually Works

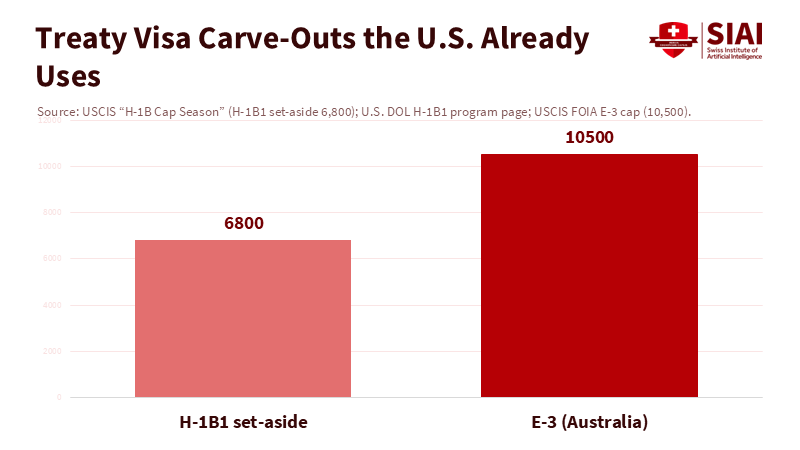

The best way to close the gap is to make visas a clear part of the deal. There’s already a precedent for this. Under the U.S.-Chile and U.S.-Singapore FTAs, 6,800 H-1B1 visas are set aside annually in the broader H-1B framework, separate from the main lottery. Australia’s E-3 category offers a country-specific professional visa with its own rules and limits. These models aren’t about providing special treatment; they are about creating a lawful, trackable bridge between economic strategy and labor markets. A U.S.-Korea deal could establish a temporary “K-1B” visa category or an expanded cap for allied technicians and engineers linked to CHIPS, with clear wage standards and training commitments. This way, every incoming specialist would work alongside American apprentices, with deadlines measured in months, not years.

The compact should rest on three pillars. First, a temporary visa class for technical specialists tailored to factory commissioning and equipment installation. This would legalize what companies currently try to do with limping visitor visas. Think 6 to 12 months of validity, renewable once, with required employer reports and an automatic expiration after the ramp-up period. Second, a skills pipeline connected to education: automatic OPT extensions in designated manufacturing STEM fields at partner sites; fast-track work authorization for graduates who join on-the-job training groups; and federal grants for community colleges in plant regions, funded directly from the investment package. Third, a reciprocity component: Korea would speed up the recognition of U.S. technical credentials and agree to co-fund transpacific apprenticeship exchanges, while the U.S. commits to consistent approvals and site-visit protocols that don’t halt projects mid-installation. These aren’t charitable concessions to companies; they are essential for taking ownership of the learning curve for modern manufacturing at home.

Critics might argue that a visas-for-investment trade-off betrays U.S. workers. However, the evidence suggests otherwise. Adding capacity in capital-heavy sectors initially depends on specialized, complementary labor. Bringing in a hundred tool installers, metrology experts, or battery chemists for six months can lead to thousands of permanent local jobs that would not exist otherwise because the plant never starts or expands. That’s why semiconductor and construction groups warn of potential shortages and why states compete for projects with training funds they know they can’t deploy quickly enough. The moral hazard isn’t foreign expertise; it’s the assumption that we can become self-sufficient without allowing time for our workforce to catch up. A clear, limited, and enforceable pathway for skilled workers is a safer solution than unofficial methods, which often result in dramatic raids and political backlash.

This also isn’t a blank check for chaebols. The agreement that opens a labor pathway should be built with commitments that most Americans would support: disclose subcontracting chains and labor brokers; verify wages among Korean and U.S. contractors; publish training completion rates and local hiring figures; and tie any tariff relief to jointly audited goals. Korea can also meet the “price” of its long period of zero tariffs by investing real capital in U.S. inland labor markets, not just on the coasts. That aligns with current investment trends—from Samsung’s Central Texas fabs to Georgia’s EV cluster. However, the compact would make the educational component clear: every project under the tariff deal would fund apprenticeships, scholarships, and skills training that continue after the initial launch.

Lastly, we should be realistic about the sequence of events. The White House’s tariff plan still has legal hurdles; the Supreme Court will evaluate the extent of presidential power over “emergency” tariffs. Seoul’s negotiators have raised concerns over foreign-exchange volatility and unresolved agricultural issues. Domestic politics on both sides could also derail a signing ceremony. These uncertainties are not reasons to avoid the visas-for-investment compact; they are motivations to create it as the first confidence-building measure—one that can move forward even if other aspects slow down. When administrations change, tariff rates can fluctuate; when we train a thousand technicians in Ohio and another thousand in Ulsan and Busan, those skills won’t disappear with one signature. In a volatile trade climate, building a strong workforce is the most valuable asset we can strive for.

We started with a number—437,000 open manufacturing jobs—and the reality: America is trying to re-industrialize faster than its labor market allows. A tariff agreement with Korea that exists only on paper won’t solve that issue; a visas-for-investment compact can. It aligns what the U.S. needs—immediate specialized capacity and long-term domestic skills—with what Korea can reliably provide: capital, process expertise, and a steady stream of students choosing U.S. schools. The September raid and its consequences were a policy failure, but they also sent a clear message. If we want timely plant construction, we must develop legal, focused, enforceable pathways for those who build them, alongside training programs for Americans to take over. That should be the trade-off for tariff relief and the goal of the investment package. Otherwise, we will continue shifting numbers on a spreadsheet while projects remain stalled. In this negotiation, visas are not a concession. They are the essential element that transforms policy into production.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AGC (Associated General Contractors of America). The 2025 Construction Hiring & Business Outlook. 2025.

Biden White House (archived). “Nearly $200 Billion of Asia-Pacific Investments Since Taking Office.” November 16, 2023.

BLS (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). Job Openings and Labor Turnover—July 2025. September 10, 2025. Table A.

CRS (Congressional Research Service). U.S.–South Korea (KORUS) FTA and Bilateral Trade Relations. Updated November 19, 2024.

CSIS. “Liberation Day Tariffs Explained.” April 3, 2025.

East Asia Forum. “Chaebol in the crossfire under Trump 2.0.” September 12, 2025.

FRED (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis) / U.S. Census. Total Construction Spending: Manufacturing (TLMFGCONS). Updated September 2, 2025.

IIE / Open Doors. South Korea: Student Mobility Facts & Figures 2024. Nov. 2024.

Reuters. “What we know about South Korea’s trade deal with the U.S.” July 30, 2025.

Reuters. “South Korea trade talks with U.S. deadlocked over forex.” September 9, 2025.

Reuters. “South Korean workers detained in U.S. head home…; Seoul seeks support for new visa.” September 11, 2025.

Reuters. “Hyundai battery plant faces at least 2–3 month startup delay…” September 11, 2025.

Reuters. “South Korea says to finalise U.S. trade deal by learning from Japan agreement.” September 8, 2025.

Reuters. “Workers say Korea Inc was warned about questionable U.S. visas before Hyundai raid.” September 9, 2025.

Reuters. “U.S. Supreme Court to decide legality of Trump’s tariffs.” September 9, 2025.

SelectUSA (U.S. Department of Commerce). FDI Fact Sheet: South Korea—2023 Stock $78.2B. 2025.

SIA (Semiconductor Industry Association). Chipping In: The Positive Impact of the CHIPS Act. Workforce projections through 2030. 2023.

USTR. “Four-Year Snapshot: KORUS.” March 15, 2016.

USCIS. “H-1B Cap Season” (H-1B1 set-aside of 6,800). August 21, 2025.

USCIS. “E-3 Specialty Occupation Workers from Australia.” July 29, 2024.

U.S. DOL. “H-1B1 Program” (Chile/Singapore allocations). n.d.

Hyundai Newsroom / PR Newswire. HMGMA Georgia investments ($12.6B) and 2025 U.S. investment plan ($21B). Mar. 26–27, 2025.

Samsung Newsroom / Governor of Texas. Taylor, Texas fab investment (≥$17B; later cost increases reported). Nov. 23–24, 2021; April 15, 2024.

Comment