Concessions Over Coercion: China's Post-Tariff Playbook for Leadership

Input

Modified

China shifts to cooperative leverage with zero tariffs and swap lines It builds influence as U.S. tariffs strain trade Schools should teach tariff-shock literacy and diversify ties

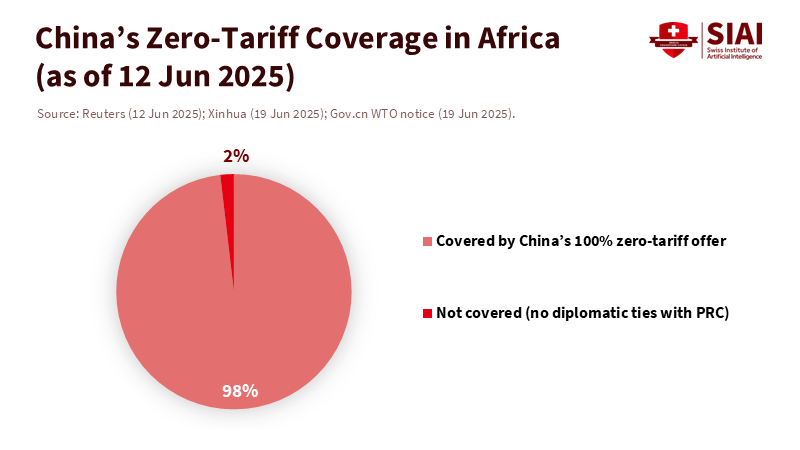

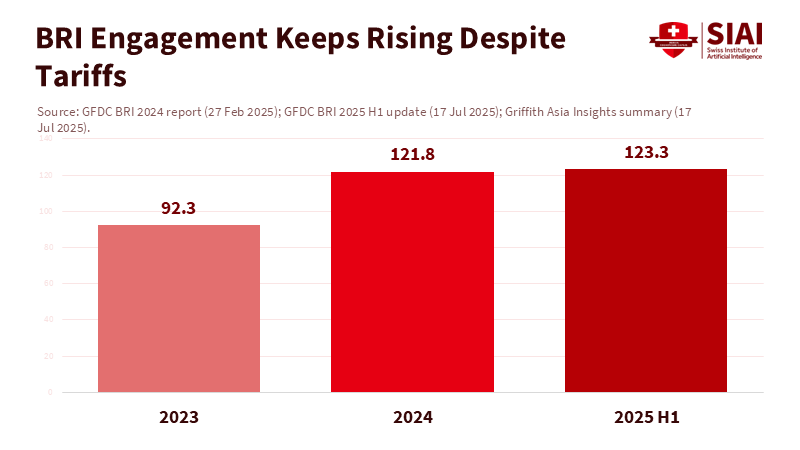

Since December 1, 2024, China has provided 100%, zero-tariff access for least-developed countries. By June 2025, it has promised to extend duty-free treatment to all 53 African partners with diplomatic ties to Beijing. This move is not a flashy megaproject; it's a straightforward benefit that helps exporters in Nairobi or Accra ship goods quickly. Meanwhile, Beijing and the European Central Bank gently renewed their €45 billion/CNY 350 billion currency-swap line until 2028. This financial support shows reliability during tough times. Although tariffs limit global trade, Chinese overseas engagement remains strong: BRI-related deals reached record levels in 2024 and continued in the first half of 2025. These actions signal a country trying to appear more cooperative and predictable amid rising tariffs.

China's shift is significant because the costs and perceptions of the new tariff landscape are substantial. By August 2025, the average effective tariff for U.S. consumers climbed to about 18–19 percent—the highest since the 1930s—while U.S.-China business sentiment fell to record lows. China's exports slowed in August, but not uniformly; sales to the United States dropped sharply, while exports to the European Union increased. Beijing focused more on hedging strategies in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Global opinions are also changing: recent cross-country polling shows a decline in U.S. favorability in many regions. At the same time, views of China improved from earlier lows—especially outside wealthy nations—despite ongoing skepticism in advanced economies. In summary, tariffs have created an opportunity for China to respond with concessions, financing, and support during crises.

From Assertiveness to Brokerage

A helpful way to understand Beijing's current actions is to see them as a shift from assertiveness to brokerage. In the 2010s, China focused on prestigious platforms, such as Confucius Institutes and high-profile infrastructure, while pursuing assertive strategies in contested security areas. Today, with tariffs in place and global demand unstable, Beijing is turning to tools that lower partners' everyday costs and reduce their risks: tariff preferences, swap lines, and development-bank support. This shift from assertiveness to brokerage implies a more collaborative and less confrontational approach, aimed at building stronger economic connections. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank now has 110 members, and its next president, Zou Jiayi, was appointed in June, indicating continuity in leadership. The PBoC's network of currency swaps has been extended or activated from Argentina to the euro area, providing liquidity in renminbi during critical periods. Meanwhile, China's trade with nearby countries under RCEP has been strong; trade with RCEP partners exceeded RMB 38.6 trillion in the first three years of the agreement and continues to represent over 30% of China's merchandise trade. Brokerage is not a gentle term; it describes how economic benefits are structured to build connections.

The diplomacy also has a different focus. Beijing's message during recent Southeast Asian tours highlighted reliability, access, and industrial partnerships rather than ideological alignment. There are signs of thawing in other regions, too. Reports in August indicated a joint effort between China and India to resume trade ties while addressing border tensions—this is not a complete resolution, but significant given the circumstances. Regionally, discussions have shifted toward risk management and building coalitions. A recent Brookings analysis urged Asia to create parallel structures for resilience as trust in U.S. economic management wavers. This view implicitly supports offers like tariff relief and liquidity assistance. Even in education and culture, strategies are adjusting. As Confucius Institutes decline in the West, Beijing is redirecting scholarships and cultural programs toward the Global South, where they are more welcomed. In this context, brokerage also involves choosing the right audiences, which in this case are the countries in the Global South that are more receptive to China's educational and cultural programs.

The Mechanics of Cooperative Leverage

Cooperative leverage, a concept that China is effectively using, relies on three main strategies: immediate, low-friction gains; reliable insurance; and visible deal flow. First, the zero-tariff expansion for African partners is easy to implement and supportive of exports. Duty-free access increases margins for agrifood and light-manufacturing exporters and can be applied to existing shipments without complicated financing. Second, swap lines and coordination with development banks provide insurance. The ECB-PBoC extension serves as a reliable safety net, while Argentina's access to a US$5 billion equivalent tranche gives its central bank breathing room, with renminbi settlements easing import costs. While small in the larger context of global finance, these measures can be crucial during unstable times. Third, deal flow matters for credibility. BRI engagement in 2024 reached about US$122 billion across 340 deals, hitting a new half-year record in early 2025, with energy and industrial projects leading the way. Simply put, partners can see the active pipeline. The concept of cooperative leverage, along with its three main strategies, helps explain how China is utilizing its economic power to influence global trade.

In contrast, tariffs provide counter-leverage for Beijing. U.S. actions have lowered trade between the two countries—China's exports to the United States dropped by about a third in August—but they have also prompted shifts toward trade diversification and regionalization. Cambodia's trade with RCEP partners grew nearly 18 percent in 2024 and continued to rise in 2025. ASEAN remains China's largest trading partner, with almost US$1 trillion in two-way trade in 2024. China is not immune to challenges; U.S. firms in China report a significant drop in business confidence, and export growth has slowed. Yet, the more Washington resorts to punitive measures—including attempts to impose secondary tariffs on third countries—the easier it becomes for Beijing to present itself as the less disruptive option. Cooperative leverage is most effective when the other side threatens penalties, framing tariff relief and liquidity as responsible stewardship rather than dominance.

China's focus on climate and development reinforces its cooperative stance. Multilateral development banks provided a record US$137 billion in climate finance in 2024, and Beijing's financing complements rather than replaces these funds. For countries seeking to address infrastructure and adaptation gaps while handling tariff impacts, China's offers of market access, project funding, and liquidity support are hard to overlook. While these offers carry risks, such as debt pressure and environmental issues, they also provide flexibility. Governments can choose from various options while maintaining relationships with Western lenders and markets. Ultimately, this creates a more competitive environment for influence where China's cooperative offers are transparent and ready to use.

What Schools and Ministries Should Do Now

Education systems are not passive in this competition for influence. Curricula, research partnerships, and international student exchanges are all part of the same influence economy as tariffs and swap lines. First, universities should incorporate "tariff-shock literacy" into business, engineering, and public policy programs. Students must learn how changes of 10–30 percent in landed costs affect procurement, supplier choices, and working capital. They should also understand how tools like currency swaps or renminbi settlements minimize risks. Faculty can use the Yale Budget Lab's public estimates of effective tariff rates for baseline assumptions, adjusting for sector variations. This approach makes geopolitics a practical teaching topic.

Second, ministries and university leaders should diversify their exchange portfolios. With visa and political uncertainties impacting Chinese student mobility to the United States and increased scrutiny of Chinese cultural centers, growth is safest in multi-country networks based in Asia and the Global South. RCEP economies already make up over 30 percent of China's trade; this economic influence should be reflected in joint degrees, stacked micro-credentials, and research collaborations that include, but do not rely heavily on, any single superpower. When programs branded with the Confucius name become politically challenging, universities should expand language and area studies through neutral partners—ASEAN hubs, campuses linked to the AIIB, or centers that also involve EU or Japanese cooperation. This mitigates political risks while keeping access open to scholarships and research funding from multiple sources.

Third, universities should establish "co-finance literacy." Research offices should train staff to combine MDB grants, BRI-linked resources, and private donations into significant labs and field projects. The 2024 surge in climate financing indicates that resources are available for applied research in energy, water, and resilient infrastructure; Chinese involvement provides additional funding avenues, though due diligence is crucial. Practical steps include incorporating standard transparency clauses, establishing AI ethics guidelines, and implementing environmental protections aligned with leading multilateral standards. This approach does not favor one side; it ensures that faculty and students can engage with any legitimate partner under conditions that uphold academic freedom and local interests.

Fourth, maintain a realistic understanding of limitations. Beijing's cooperative strategy coexists with aggressive security actions and industrial oversupply that can disrupt local markets. Recent analysis from The Diplomat highlights that China's regional communications often minimize security issues important to its neighbors. Data from AmCham in Shanghai shows that foreign companies continue to perceive rising geopolitical risks. These tensions suggest that educators and policymakers should include "exit ramps" in any initiatives tied to China—such as alternative funding sources, credit portability, and escrow provisions in contracts—to ensure that political changes do not leave students or projects stranded. Good faith collaboration can coexist with thorough contingency measures.

Cooperation is not a sentimental idea in 2025; it's a competitive strategy. The most revealing statistic remains Beijing's decision to provide full duty-free access across 100%of tariff lines for its least-developed partners and to extend this policy throughout Africa. Coupled with a renewed swap line with the ECB and record deal flow through development channels, the pattern is clear: China aims to be the low-friction, high-reliability player in a chaotic trading system. The United States, by relying on tariffs and secondary penalties, is banking on coercion to maintain its position. This strategy may yield results in some areas. However, in classrooms, ministries, and boardrooms across the Indo-Pacific and Africa, the everyday considerations of duties, delivery times, and liquidity support matter more than rhetoric. The challenge for educators and policymakers is to adapt to this reality: integrate tariff-shock literacy into curricula, diversify partnerships for resilient regional networks, and fund research through clear, multi-partner systems. If we prioritize competence over ideology, we can promote open academic exchange, lessen susceptibility to political fluctuations, and prepare the next generation to navigate a world where influence is earned through practical concessions that can be applied immediately.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Al Jazeera. (2025, August 20). Did Trump’s tariff war force India and China to mend ties?

American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai / Reuters. (2025, September 10). U.S.-China tensions drive business confidence to new lows, survey says.

Brookings Institution. (2025, September 8). Solís, M., Hsu, K., & García-Herrero, A. Asia must prioritize regional cooperation for economic resilience amid tariff uncertainty.

ECB. (2025, September 8). ECB and People’s Bank of China extend bilateral euro–renminbi currency swap arrangement.

East Asia Forum. (2025, September 12). Zeng, K. China’s diplomatic influence on the line as it navigates the US tariff storm.

East Asia Forum. (2025, September 13). Chey, J. Confucius Institute decline signals China’s soft power shift.

Financial Times / Yahoo Finance compilation. (2025, September 13). U.S. urges G7 to impose up to 100% tariffs on China and India over Russian oil.

Green Finance & Development Center (FISF, Fudan). (2025, Feb. 27 & Jul. 17). BRI Investment Reports 2024 and 2025H1.

Pew Research Center. (2025, July 15). Views of China and Xi Jinping (2025 update).

Reuters. (2024, Dec. 4; 2025, June 12; 2025, Sept. 8). China duty-free access for African LDCs; China says it will remove all tariffs on African exports; ECB–PBoC swap extension coverage.

The Diplomat. (2025, August 7). Li, Z. China’s Diplomatic Campaign Following Trump’s Tariffs.

U.S.–China trade and macro indicators:

— Associated Press. (2025, Sept. 9). China’s export growth slows in August as tariffs bite.

— Yale Budget Lab. (2025, August 7). State of U.S. Tariffs.

Xinhua / NDRC (via NDRC English). (2025, Jan. 31). Cambodia’s trade with RCEP members hits $34.52 billion in 2024.

Regional trade architecture and China–RCEP commerce: China Briefing. (2025, Sept.). RCEP trade through China: three-year update (RMB 38.57 trillion).

Comment