The Medium, Not the Message: Why “More” ECB Talk Won’t Anchor Expectations Unless It’s Better

Input

Modified

Households’ inflation beliefs move more with media framing than ECB verbosity Extra, unscheduled talk can backfire; clarity, timing, and audiovisual formats anchor expectations Make communication a measurable policy tool with simple targets and state-contingent triggers

When average global inflation was around 2.4% this spring, households in various countries still expected about 8% inflation over the next year. This gap, known as the “perception wedge,” is significant; it shows that official messages are not reaching the people whose spending drives the economy. If citizens think prices will rise three times faster than they actually do, they start buying sooner, resist price drops, and push for wage increases that add to stickiness. Central banks have responded by increasing communication with more speeches, longer statements, and additional press conferences. However, the evidence suggests that the most critical factor is not just the number of words spoken from the podium. It matters who delivers the message, when attention is at its highest, and how clearly the message is communicated. Households do not analyze press conference transcripts; they take in interpretations from television anchors, online news sources, and their social networks. If communication does not reach those channels in a transparent and trustworthy way, more words can make the situation worse.

The medium moves expectations

Two main facts outline the communication issue. First, households overestimate short-term inflation significantly, even as the main rates drop. This discrepancy is evident across countries during the disinflation of 2025. Second, households follow media coverage of monetary policy rather than central bank documents. A recent BIS working paper used large language models to assess the sentiment of post-meeting Federal Reserve communications and compare it with the news coverage that followed. It found a strong link between the official tone and media framing. Importantly, news sentiment—rather than the central Bank’s words—changes household inflation expectations, especially during high inflation periods. Press conferences enhance this connection, and the Q&A session is the most influential part. Yet, the paper finds no direct impact of official statements on households without media involvement. In short, the person delivering the message is just as important as the message itself, and the audience's role in shaping their own expectations is crucial.

A large body of research supports this finding: central bank communication can shape household beliefs, but only when it is easy to understand and aware of the context. Blinder’s 2024 review highlights that speaking to the public, not just market professionals, requires a different approach. Shorter, simpler, and clearer messages are needed. The ECB’s 2023 communication strategy acknowledges this same limitation. Attention spans are short, false information spreads faster than facts, and press releases have increased sevenfold in length between 2007 and 2020. If the ECB’s message is lengthy and complicated, the public either ignores it or hears it through filtered channels that prioritize emotion over subtlety. So, the key to credibility lies in clarity, brevity, and appropriate repetition, not in longer statements.

Recent European data demonstrate the effectiveness of targeted clarity. In May 2025, the ECB’s Consumer Expectations Survey reported median 12-month inflation expectations at 2.8%, three-year expectations at 2.4%, and five-year expectations at 2.1%. These figures are much closer to the target than the global 8% perception wedge, likely reflecting a year of consistent messaging around a goal of “back to 2%.” However, this improvement is fragile. ECB officials warn that many households still misunderstand their own real-income gains and remain hesitant to spend. This credibility issue demands straightforward language and better framing. The lesson is not that central bank communication is pointless; instead, it shows that citizens react positively when the message is clear, presented in engaging formats that they value, and timed to catch their attention—conditions that lengthy, text-heavy briefings often fail to meet.

When more talk backfires

At times, increasing communication can be counterproductive. The classic Hirshleifer effect demonstrates that incomplete or poorly timed information can exacerbate outcomes by exacerbating risk-sharing issues. In monetary policy, unscheduled announcements can create volatility by surprising markets about timing instead of content. Today’s media landscape intensifies this risk, as off-cycle remarks can generate discussions that households interpret as signals of disorder, even if the underlying policy remains the same. In these situations, the best response is to curate information, not expand it, ensuring clarity arrives on expected dates while minimizing irrelevant background noise.

“More disclosure” can also undermine forward guidance by bringing uncertainty to the forefront that households cannot process. New research shows that communicating uncertainty, while honest and sometimes essential, can reduce the impact of guidance shocks on bond yields and expectations. This happens because audiences tend to focus on the negative aspects of conditional forecasts. Disagreement within policy committees adds another layer of complexity. Evidence shows that publicizing internal disagreements increases households’ inflation uncertainty, which can weaken the intended anchoring. This doesn’t advocate for secrecy; instead, it calls for limited transparency. Explain the target, the rules, and conditions that trigger changes, but avoid detailing every model caveat in real time.

Another crucial constraint that isn’t often mentioned is financial literacy. Less than half of respondents in the euro area can correctly answer three basic literacy questions. Households with low literacy pay less attention to interest rates and form more uncertain expectations. In such circumstances, extra paragraphs only add noise. What enhances understanding is the format. Experiments show that audiovisual messages—short videos combining voice with visuals—are more effective in guiding beliefs toward the 2% target than text alone, especially for less literate audiences. Communication failures stem more from a mismatch between medium and audience than from a word shortage.

Less but better: a design for ECB outreach

If outside experts and the financial press already provide reasonable forecasts, the ECB’s role isn’t to produce more content; it’s to deliver credible, well-timed messages that the media can share intact. Four design strategies emerge from the evidence. First, schedule consistency: keep policy-related communication on a predictable timetable, saving off-cycle remarks for genuine shocks. The BIS pass-through study indicates press conferences are vital for shaping next-day coverage; they should be designed for that purpose with a concise narrative and a clear “what would change our minds” frame. This is where the ECB's influence on media framing is most pronounced. Avoid unnecessary quasi-official interviews that create timing confusion.

Second, focus on format: start with audiovisual explainers and a one-screen “at a glance” statement before presenting lengthy text for specialists. Studies show that video is more effective than text for anchoring, especially for those with lower financial literacy. The ECB's movement toward layered statements recognizes this reality. This is not merely a cosmetic change; since households primarily encounter the ECB through TV and online clips, designing for those formats—using short sentences and concrete examples—helps the institution take back control of its narrative from third-party interpretations.

Third, target messages: during times of high attention, repeatedly convey three key points until they become common knowledge: “Inflation will return to 2%,” “Here’s the path that could speed up or delay that,” and “Your mortgage and deposits respond this way.” The objective is to narrow the perception wedge that leads households to expect 8% inflation in a world where it should be 2–3%. When news sentiment turns hawkish, households lower medium-term expectations by about 0.5–0.9 percentage points; that is the moment to reinforce commitment and state the trigger conditions. Conversely, when sentiment shifts dovish, present the path with clear guidelines to avoid unwarranted optimism. The focus should be on matching the media narrative rather than drowning it out.

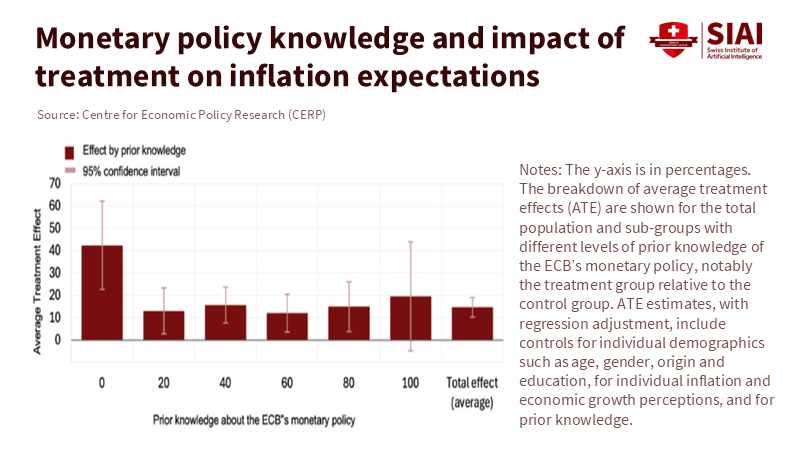

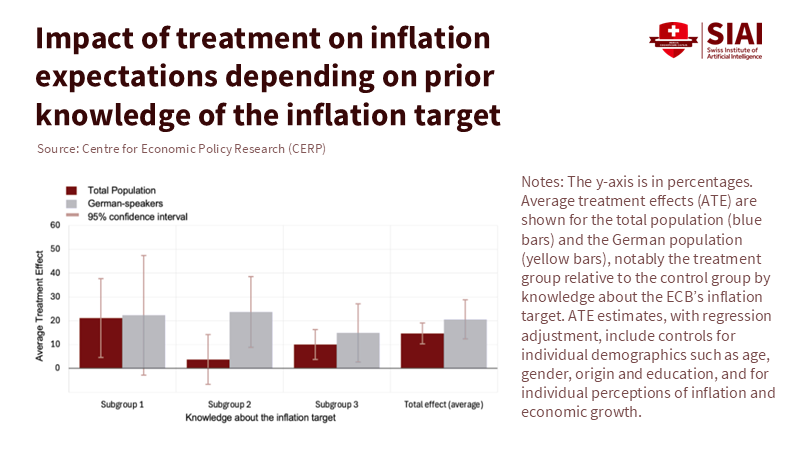

Fourth, implement measurable accountability: treat communication as a policy tool with specific targets and indicators. A suitable measure could be the belief-perception gap, which is the difference between realized 12-month inflation and the median 12-month household expectation in the CES. Set a corridor—for instance, maintain the gap within ±1.5 percentage points for three months—and publish whether this goal is met. Where gaps widen, use randomized A/B tests in various euro-area languages to compare the effects of different formats (text vs. video), content (target-only vs. target-plus-context), and narratives (household budgets vs. macro aggregates). Randomized controlled trials in the U.S. and Europe have shown that concise, target-focused communication aids in anchoring, and in certain situations, boosts consumption responses; the ECB could make these tests a standard part of its strategy.

Two important caveats should be highlighted. Communicating uncertainty is not a failure; it shows humility—however, the manner of communication matters. Instead of dense fan charts, explain one or two key triggers in simple terms (“If core inflation stays above X and wage growth above Y for Z months, rates will…”) and maintain that template for a year. Also, public discussions of disagreements need context: households should understand that differing views reflect a thoughtful process within a shared 2% goal, rather than indicate that policy is lost. The proper framing can help prevent misunderstandings from healthy debates.

Finally, the ECB should utilize non-official communicators without losing control of the content. The BIS findings suggest that households respond strongly to news through trusted channels. This indicates a two-step strategy: (1) pre-brief reliable outlets with embargoed outlines that connect top-level decisions to consumer-relevant examples, and (2) spread short, shareable clips that journalists and educators can use. A recent Fed speech pointed out that households often respond more to social media and personal contacts than to traditional sources. Designing resources for those networks, available in all EU languages, can transform the ECB’s messages into knowledge for citizens.

To anchor expectations, we need to address the perception wedge. The critical number is 8: when people anticipate 8% inflation in a world where it should be 2–3%, no amount of technical language will change their minds. The research is clear: press conferences are important because they influence the news, news sentiment shapes household beliefs, and audiovisual, clear communication is more effective—especially when attention is heightened and literacy levels vary. Increasing talk for its own sake can lead to disruption instead of stability. The ECB’s task is not to say more, but to communicate better: through tighter schedules, simpler formats, focused messages, and public metrics to gauge the effectiveness of their communication. Suppose the Bank creates a communication framework that consistently closes the belief-perception gap and keeps three-year expectations close to the target. In that case, households will adjust their behavior long before any models do. Anchoring will become a fundamental aspect of the system, not just a hope tied to press releases.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Ash, E., Mikosch, H., Perakis, A., & Sarferaz, S. (2024). Seeing and Hearing is Believing: The Role of Audiovisual Communication in Shaping Inflation Expectations. CEPR Discussion Paper DP18792 / SSRN working paper.

Banerjee, A. N. (2002). On the “Hirshleifer Effect” of Unscheduled Monetary Policy Announcements. University of Southampton Discussion Paper.

Blinder, A. S. (2024). Central Bank Communication with the General Public. Journal of Economic Literature.

Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y., & Weber, M. (2019). Monetary Policy Communications and Their Effects on Household Inflation Expectations. NBER Working Paper No. 25482.

De Fiore, F., Maurin, A., Mijakovic, A., & Sandri, D. (2024). Monetary policy in the news: communication pass-through and inflation expectations. BIS Working Paper No. 1231.

De Fiore, F. (2025). Household perceptions and expectations in the wake of disinflation. BIS Bulletin No. 104.

European Central Bank (2023). Communication and monetary policy (speech text; accessibility and humility; press-release length statistic).

European Central Bank (2025). Consumer Expectations Survey results – May 2025 (press release; median expectations figures).

Federal Reserve Board (2025). Speech by Vice Chair Jefferson on central bank communication and household channels.

Grebe, M. (2023). Dissent in the ECB’s Governing Council increases households’ inflation uncertainty (SUERF Policy Brief / RCT evidence).

Hirsch, P. (2023). Breaking Monetary Policy News: The Role of Mass Media in Household Inflation Expectations (CESifo Working Paper).

Wyplosz, C. (2022). Communication is not just talking (European Parliament study).

Ying, S., et al. (2025). Does monetary policy uncertainty moderate the forward-guidance shock? Journal of International Money and Finance (in press).

Comment