The Real Cost of a Quiet Sunday

Input

Modified

Sunday bans add about 1.4 miles of travel per trip They now mainly push shoppers online Targeted labor and digital-market policies work better

One key number shapes our understanding of Sunday trading rules: 1.4 miles. This figure represents the extra distance the average shopper effectively “pays” each time a Sunday-morning retail ban is enforced. This insight comes from new GPS-based evidence from North Dakota's 2019 deregulation. The study’s authors estimate that the welfare loss from the ban is like moving every affected store 1.4 miles farther away. Another discussion paper suggests the estimate is a little higher, around 1.7 miles. Although that distance seems small, it adds up with millions of weekly trips, translating into time, fuel, and emissions. According to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency data, driving 1.4 miles in a gasoline car emits about 560 grams of CO₂. This means the policy turns a shared day of rest into a measurable burden for households and the environment. The individual impact may be slight for one family, but it adds up for society and can easily be overlooked—unless we really look at it.

The hidden distance cost—and why it demands immediate attention

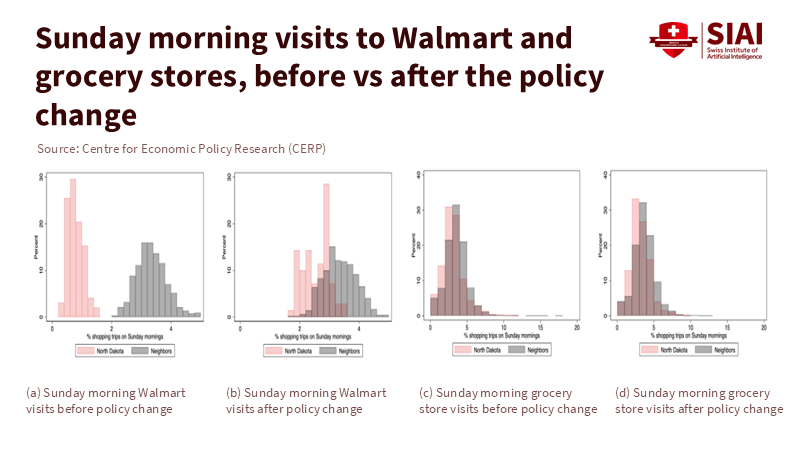

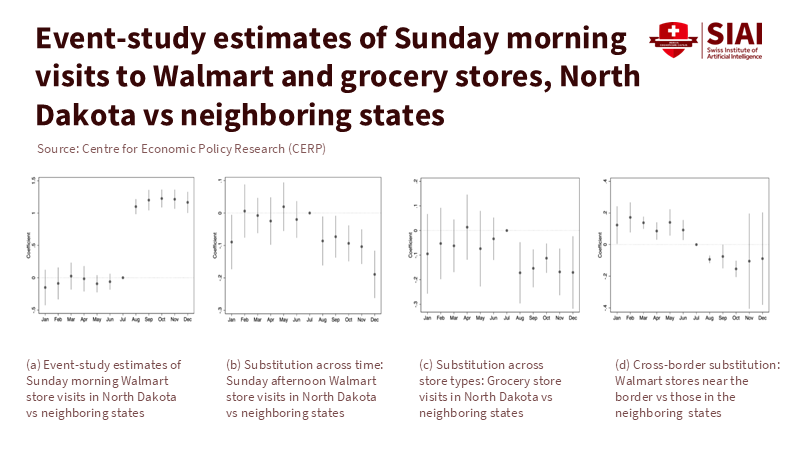

Recent GPS data tell us that people don’t shop less when stores close on Sunday mornings; they change their routes. Shifts in timing, cross-border shopping, and switching store types account for much of the behavior change, leading to a surge in Sunday visits as bans are lifted. Economically, the restriction acts like a tax, increasing search and travel costs while reducing competition. As Hotelling’s linear-city theory suggests, when access narrows, consumers travel farther to find what they need, and firms adjust their strategies to maintain market share. The new data help us see a long-held trade-off: the social value of a coordinated day of rest versus a collection of minor private inconveniences that lead to a significant public cost. Policymakers shouldn't overlook these costs just because they show up in minutes and miles.

Korea’s situation sharpens this lesson. Since 2012, large discount retailers and hypermarkets in Korea have been required to close on two days each month under the Distribution Industry Development Act. Many areas chose Sundays for these closures to protect local markets and provide workers with dependable rest. However, the rule has been manipulated and weakened; big chains increasingly move closures to weekdays, while online shopping continues as usual. Reports also indicate that some consumers are doing exactly what the North Dakota results predicted—they are shopping online. A 2025 analysis by JoongAng Daily found that Sunday closures likely led consumers to e-commerce, rather than traditional markets that policymakers aimed to support. The goal—to back local businesses and protect labor standards—is noble; however, the method of imposing blanket restrictions on large stores seems less effective in an economy where the nearest shop often exists on a smartphone.

Korea’s role in the e-commerce era

To understand why this restriction works differently today than it did a decade ago, we must consider demand. Korea is one of the most digitized retail markets in the world, with online sales growth vastly outpacing that of physical stores year after year. Government data show online retail booming in 2024, even as some in-store categories slow down. Industry reports indicate that Korea is among the global leaders in e-commerce penetration. When physical access is limited, digital options are waiting to fill the gap. This situation complicates the original policy agreement. If a Sunday closure mainly shifts shopping from hypermarkets to apps, local street shops gain little and sometimes lose the foot traffic that larger stores attract. What remains is the distance-equivalent cost for drivers and a sorting process that benefits online platforms already enjoying economies of scale. The effects can be unfair: car owners incur fuel costs, while non-drivers pay delivery fees and wait for service.

Policymakers have taken notice and adjusted in some areas. Early in 2024, authorities hinted they might move required closures to weekdays and relax rules around online sales, recognizing both worker welfare and consumer needs. News articles documented retailers’ quick shifts away from Sunday closures, and follow-up analyses recorded a continued movement of demand online, including cross-border shopping and the rise of ultra-low-price platforms. Each development highlights a broader issue: time-based regulations that once provided a level playing field for physical stores now channel traffic into digital platforms that face different rules—such as consumer protection, data privacy, product safety, and payment reliability—where Korea has had to step in with separate regulations. When a policy's effectiveness changes, the policy must adapt accordingly.

From blanket bans to smarter protections

To protect small retailers and ensure rest without imposing heavy travel costs, the tools used must be updated. A better approach would separate worker protections from market structure goals. For labor rights, including scheduling flexibility, extra pay for Sundays, and guaranteed weekend rotations, can directly address worker welfare without forcing consumers to drive, similar to discussions in Britain on trading hours. For market structure, targeted support for small businesses, including digital onboarding, shared logistics, local vouchers, and reduced business rates, tackles the real competitor: online platforms, not just large stores. The UK’s experience with a six-hour Sunday limit for large stores demonstrates that limited liberalization can work alongside worker protections. Yet even there, the case for local flexibility and updated enforcement has grown. The focus should be on how to keep Sundays special without imposing extra travel burdens on families.

The measurement approach should change, too. Distance-equivalent welfare metrics can turn abstract inconveniences into something tangible. For instance, if a metropolitan area sees 200,000 grocery trips affected by a closure, and each trip adds 1.4 miles, that totals 280,000 extra miles. This equates to roughly 112 metric tons of CO₂, based on the EPA’s 0.4 kg per mile calculation, before considering traffic congestion and time. These rough numbers may not be ready for policy application, but they help structure debate and enable direct comparisons across cities and years. They also clarify concerns about a potential rebound effect: if more trips shift to Saturdays, congestion may worsen. The GPS study’s breakdown highlights the significant adjustments that occur across different times and types of stores, not just daily. Regulators can test alternative schedules or exceptions and observe real consumer behavior, rather than just sales figures. Evidence first, ideology second.

A second adjustment involves jurisdiction. Time-of-week rules are enforced locally, but shopping habits cross digital boundaries. When a closure sends shoppers to platforms based outside the area, tax revenue, safety oversight, and data governance shift with them. Korea has already negotiated platform safety agreements and investigated data practices as international e-commerce continues to grow. This enforcement work does more to support local small businesses than simply posting signs that say “Closed this Sunday.” A modern “Sunday policy” should therefore focus on three areas: ensuring the right to rest, enhancing the digital skills of small businesses, and rigorously overseeing the online marketplace, just as we do for physical store hours.

The third adjustment relates to competition policy. While the idea that companies cluster toward the middle holds offline, the online world operates differently. Algorithmic searches and delivery networks recreate distance through fees, rankings, and shipping times. Small physical stores that relied on traffic from larger stores now need new ways to be discovered and achieve local presence. Municipalities could pilot “digital main streets,” where local businesses share fulfillment services and streamlined searches across verified inventories. Vouchers linked to these networks can offer support without dictating the operational hours of larger stores. The objective should not merely be to preserve the charm of Sundays, but to ensure the additional miles we ask families to drive are truly justified when compared to cheaper, cleaner, more innovative options that maintain choice. Tradition doesn't have to rely on cars.

We began with a small figure that reveals a significant truth. A 1.4-mile distance-equivalent loss per trip might not make the news, but it accumulates into substantial time, fuel, and emissions across a week. In Korea and beyond, the original intent behind Sunday restrictions—protecting workers and small stores from relentless hours and large competitors—has weakened in a retail environment where the closest “shop” often exists on a mobile app, and closures disadvantage some families while benefiting platforms. The correct response is not to eliminate Sundays but to update them: safeguard rest with targeted labor measures, support small businesses where real competition occurs, measure costs in relatable terms, and enforce consumer protection online with the same rigor we apply to assessing storefront hours. If we are going to impose a distance toll for a cultural choice, we must ensure it delivers what we believe it does. Otherwise, we are simply wasting Sundays—and fuel.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). (2022). Shop opening hours and Sunday trading (UK House of Commons Library Briefing SN05522, April 13, 2022).

Donna, J. D., Hinnosaar, M., Hinnosaar, T., & Trindade, A. (2025, July 4). Opening Hours and Consumer Behavior: Evidence from GPS Data and Deregulation (CEPR Discussion Paper DP20409 / SSRN Working Paper).

Indepen. (2006). The economic costs and benefits of easing Sunday shopping restrictions on large stores in England and Wales (Report for the UK Government).

JoongAng Daily. (2024, January 15). Supermarkets move contentious mandatory closure days to weekdays.

JoongAng Daily. (2025, April 15). Sunday supermarket closures could be pushing consumers to shop online, study finds.

Korea.net / Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE). (2024, April 29). Korea’s retail industry grows; online sales surge.

MobiLoud. (2025). E-commerce share of retail sales by country (2024 update).

PCMI / Payments CMI. (2025, June 19). South Korea 2025: Payments & e-commerce data and trends.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2025, June 12). Greenhouse Gas Emissions from a Typical Passenger Vehicle.

VoxEU / CEPR. (2025, September 12). Donna, J. D., Hinnosaar, M., Hinnosaar, T., & Trindade, A., The hidden toll of Sunday store closures: New evidence from GPS data.

Wikipedia. (2025). Hotelling’s law (summary and references to Hotelling, 1929). Cited for definitional context only.

Comment