Europe's Fiscal Rubicon: Balancing Budgets in an Age of War, Yields, and Waning Guarantees

Input

Modified

Europe must consolidate while rearming Compliance still lags; credible plans are urgent Reprioritise spending and taxes; leverage EU-level financing

By July 2025, the UK's public debt had reached 96.1% of GDP, the highest level for the country in modern peacetime, excluding the pandemic-induced spike in 2020. France ended 2024 at 113% of GDP with a deficit of 5.8%, while Germany's debt ratio was around 62.5%, even before increased defense spending. These figures underscore the urgency of the situation, with the impact of the pandemic, energy crisis, and war, alongside NATO's goal of increasing defense spending from 2% to 5% of GDP by 2035. The EU has reintroduced oversight of deficits and established stricter spending frameworks, creating exemptions to support itself and Ukraine. The challenge lies in consolidating resources while rearming, necessitating a shift from "stimulus by drift" to a structured reprioritization focused on immediate savings and targeted investments.

Reframing the Problem: From Temporary Escape to Permanent Trade-offs

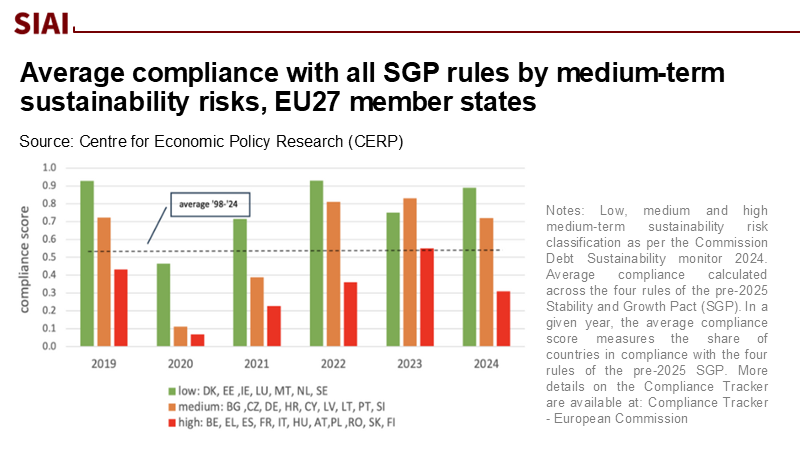

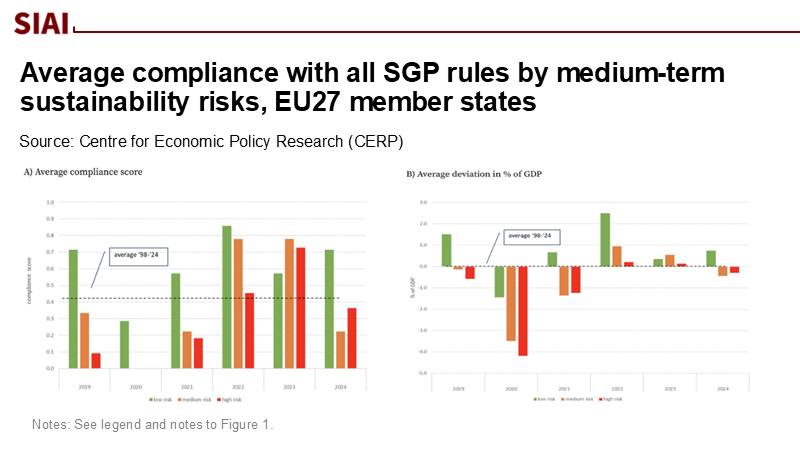

The prevailing narrative views Europe's fiscal looseness since 2020 as a temporary measure to bridge crises. That story was plausible when the general escape clause, which allowed member states to deviate from the EU's fiscal rules in times of severe economic downturn, was in effect and suspended the EU rules; it is untenable now that the clause has been removed and the new framework is in force. The fundamental policy question is not whether to "return to normal," but how to consolidate while rearming. In 2024, the EU's surveillance regime was characterized by a combination of old and new rules, and several governments took advantage of this ambiguity. The result is a tougher starting point for implementing country-specific net-expenditure paths in 2025 and beyond. Meanwhile, the security environment has shifted: the NATO spending anchor moved decisively higher, the U.S. strategic focus is more diffused, and Ukraine's defense and reconstruction needs are now built into Europe's baseline. The reframing matters because it forces choices: which programmes shrink, which taxes rise, and which investments must be protected to prevent consolidation from strangling the very growth that stabilises debt.

The Numbers That Shape the Constraint

France's fiscal arithmetic is stark. INSEE reports a 5.8% general-government deficit for 2024 and Maastricht debt at 113% of GDP. The IMF's July 2025 Article IV report projects a 2025 deficit of approximately 5.4% without additional measures. It warns that, absent credible consolidation, debt will continue to rise—an assessment echoed by the EU's corrective procedure. Markets noticed: French spreads versus Bunds widened repeatedly over 2024–2025. Across the Channel, the UK's PSND stands at 96.1% of GDP as of July 2025; the OBR describes borrowing oscillating near 5% of GDP for four years running and notes that 10-year gilt yields around mid-2025 place UK borrowing costs near the top of advanced economies. Germany is better placed—62.5% debt at end-2024 and a deficit of nearly 2.8%—but growth has been weak, and court rulings have constrained off-budget maneuvering, complicating fiscal planning. Those three benchmarks—France/UK/Germany—define the space in which Brussels now presses for credible, medium-term adjustment without triggering a recession.

Security Rewritten: From 2% to 5% and the Cost Curve to 2035

NATO's new political commitment—to plan for 5% of GDP on defense by 2035—is a fiscal accelerant. Start with a transparent back-of-the-envelope calculation: the EU-27's GDP is roughly €16 trillion; the current average defense effort has recently hovered around the low twos. Each additional percentage point of GDP amounts to ~€160 billion annually. Moving from ~2% to 5% implies roughly €480 billion more per year at the 2035 horizon, even if phased. That is not a single-year bill; it is a glide path requiring ~0.25 percentage points of GDP a year in many countries. The Commission and EIB have floated mechanisms to expand defense-industry finance and contemplated joint borrowing tranches; EU fiscal guidance has also explored national escape-clause flexibility specific to defense outlays. But exemptions do not print resources. Corresponding cuts or revenue increases must offset every euro diverted to defense, unless growth increases the denominator. The strategic lesson for budgets is straightforward: plan multi-year budgets, leverage procurement gains from scale, and attract private capital where dual-use infrastructure and supply chains permit.

What Brussels Is Actually Doing—and Why It's Not Enough

The EU has reformed its fiscal rules: the 3%/60% references remain, but the core operational anchor is a country-specific net-expenditure path over four to seven years, with corrective arms reactivated and excessive-deficit procedures opened for seven member states in July 2024, including France. In parallel, the EU is financing Ukraine through a €50 billion Ukraine Facility (2024–2027), while preparing to repay NGEU grants from 2028, which will add medium-term pressure to the EU budget. On defense, the Commission has proposed standard borrowing options, industry programmes, and escape-clause flexibility to avoid pro-cyclical cuts as security spending rises. These are coherent steps, but they leave a gap between ambition and capacity. The 2028–2034 MFF proposal, at ~1.26% of GNI, includes headroom to service the NGEU but not to shoulder the full defense surge. Without broader own resources—or a larger standard instrument—the Union risks pushing consolidation down to capitals precisely when national balance sheets are tightest. Collective action is needed to bridge this gap and ensure the stability and security of the EU.

A Practical Roadmap: Balance Now, Invest Where It Counts

First, front-load structural savings that do not sap growth: indexation trims where social safety nets overshoot median-income gains; procurement and subsidy reviews that retire crisis-era supports; and administrative digitalisation that lowers unit costs. Second, shift the tax mix toward bases least harmful to growth—property and land value, where under-taxed, high-end consumption, and externality pricing—with guardrails in place to ensure distributional fairness. Third, ring-fence high-multiplier investments, such as energy-system upgrades, freight rail and port corridors, and education/skills, precisely the public goods that raise potential output and crowd in private capital. Fourth, utilize EU-level financing for shared priorities—such as air defense architecture, munitions ramp-up, and Ukraine's macroeconomic support—so that national consolidation can proceed without compromising collective security. Finally, sequence reforms with defense ramp-up: map the NATO glide path into each medium-term expenditure plan, utilizing any approved national defense escape clause transparently and temporarily, with sunset tests and debt stabilization metrics attached. This is not austerity; it is reprioritisation under constraint, and it requires strategic planning and foresight.

Anticipating the Critiques—and Answering Them

One critique insists that Europe can "grow out" of debt without consolidation. The arithmetic disagrees. The OBR shows that the UK's borrowing has remained at nearly 5% of GDP for four consecutive years, while market rates have normalised; servicing costs rise faster than trend growth unless primary balances improve. Another critique warns that consolidation will crush growth. That depends on composition and timing: trimming low-multiplier transfers and tax expenditures while protecting public investment yields a different macro path than indiscriminate cuts. A third critique says, "France is Greece." The analogy fails on institutions: the ECB now has multiple anti-fragmentation tools (OMT, PEPP reinvestments, and the TPI), euro-area banks are better capitalised, and France's market depth and tax capacity differ fundamentally from Greece's pre-2010 state—even if current spreads are a flashing yellow. The final critique argues that defense should be exempt. Exemptions can smooth the path, but they do not eliminate intertemporal budget constraints; the bill must be paid, preferably through reforms that increase potential output rather than relying solely on higher debt.

Implications for Classrooms, Campuses, and Ministries

For educators and university leaders, the pivot to skills-intensive rearmament and resilience will shift demand into engineering, cyber, AI, logistics, and advanced manufacturing. Curricula must align with dual-use needs—such as secure software, materials science, and systems integration—while safeguarding academic independence. For administrators, the budget squeeze will sharpen scrutiny of programme effectiveness and unit-cost transparency; institutions that demonstrate verifiable outcomes in employability and innovation will fare better when ministries triage funding. For policymakers, the coalface is medium-term planning: publish credible net-expenditure paths that show not only how deficits fall, but what is protected and why; coordinate cross-border procurement to lock in scale economies; and channel EU instruments toward projects with apparent spillovers. The test is whether Europe can raise its defense and deterrence without flattening the investment that makes its economies competitive. A single headline ratio will not measure success, but rather whether debt dynamics, growth, and security each move in the right direction together.

Back to the Statistic, Forward to the Choice

The key figures—France's debt at 113% and a deficit of 5.8%, the UK with debt at 96.1% of GDP and borrowing close to 5%, and Germany's debt ratio in the mid-60s, creeping up due to increased defense spending—serve not just as alerts; they define the limits of policy options. Europe's task is not to pick between consolidation and security, but to realize that security without consolidation is not financially feasible, and consolidation without investment is counterproductive. The way to navigate this dilemma is through a careful realignment of priorities: making structural savings to create fiscal space, implementing tax shifts that support growth, utilizing EU-level mechanisms to pool risks for genuine European public goods, and establishing a clear defense funding strategy integrated into credible medium-term plans. If policymakers view the current limitations as an opportunity rather than a constraint, the continent can finance its defense, stabilize its debt, and maintain the social contract that ensures legitimacy. The turning point is achieved not through mere words, but through budgets that are consistently balanced—regardless of the challenges that arise.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank of England/Office for Budget Responsibility. Fiscal risks and sustainability – July 2025. (OBR). 8 Jul 2025.

Bundesbank. "German general government debt up in 2024… debt ratio down from 62.9% to 62.5%." Press release, 31 Mar 2025.

Council of the EU. "Stability and Growth Pact: Council launches excessive deficit procedures against seven member states." 26 Jul 2024.

European Commission. "Political agreement on the Ukraine Facility." 2024; and Staff Working Documents on NGEU repayment.

European Commission

European Commission, Economy & Finance. "Excessive deficit procedures – overview." 2024–2025.

European Commission / European Parliament Research Service (EPRS). Future of EU long-term financing. Feb–Jul 2025; includes NGEU repayment from 2028 and MFF 2028–2034 proposal ~1.26% GNI.

European Parliament, EGOV Unit. Defence financing and spending under the Economic Governance Framework. Mar & May 2025.

Financial Times. On UK market context and borrowing costs; on European defense financing debate. 2025.

Office for Budget Responsibility

IMF. France: 2025 Article IV Consultation—Press Release and Staff Report. 11 Jul 2025.

INSEE. "In 2024, the public deficit reached 5.8% of GDP, the public debt 113.0% of GDP." 27 Mar 2025.

NATO. "Defence expenditures and NATO's 5% commitment—Hague Summit 2025." 24 Jul 2025.

Office for National Statistics (UK). Public sector finances, July 2025. 21 Aug 2025. (Debt 96.1% of GDP.)

Politico / Reuters. European fiscal enforcement and defense-financing proposals, 2024–2025. (EDP openings; EU-level borrowing for rearmament.)

VoxEU/CEPR (Larch, 2025). "Dangling fiscal surveillance: EU fiscal policies in 2024." 25 Aug 2025.

White & Case (client alert). "Commission's 2025 defense package overview." 7 Apr 2025.

WIIW Policy Note (2025). The new EU fiscal framework and implications for public spending. 2025.

Ukraine Facility. European Commission and EP Think Tank pages, 2024–2025. (Overall envelope €50bn 2024–2027.)

Comment