Splitting the Synergy Pie: How the EU–Asia Pacific Pact Can Actually Power the Green Transition

Input

Modified

The EU and Asia Pacific should move from competition to surplus-sharing in green energy Tools like carbon contracts and CBAM credits can ensure fair distribution of benefits This strategy will enhance investment and strengthen global partnerships

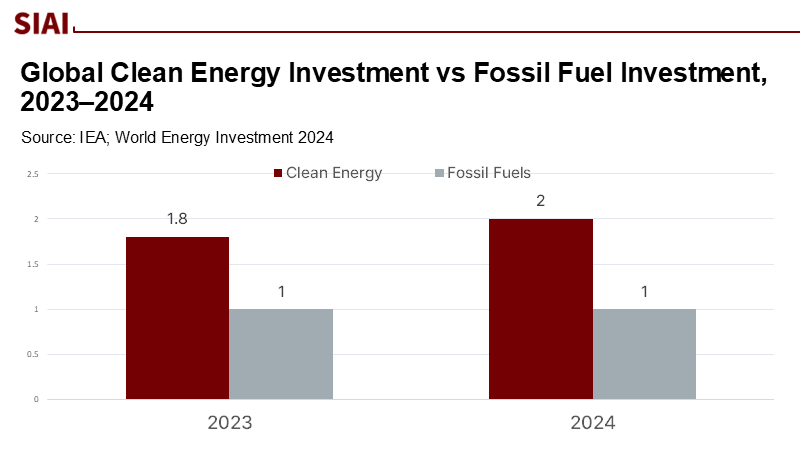

Investing one euro in Europe's electricity grid can save over two euros in future costs, based on ENTSO-E's modeling. These savings depend on coordinated progress in infrastructure, production, and regulations across borders. In 2024, global clean energy spending hit about USD 2 trillion, with total investments in energy exceeding USD 3 trillion for the first time. Battery pack prices reached a record low, and around 585 GW of new renewable energy capacity was added, totaling approximately 4,448 GW worldwide. Successful industrial partnerships may exist, but without guidelines for sharing benefits, they struggle. The key objective for the EU and the Asia Pacific should be establishing equitable surplus distribution to incentivize prompt action.

From comparative advantage to surplus-sharing

The familiar story suggests that Europe offers regulatory certainty, deep finance, and high-ambition consumers, while the Asia Pacific delivers manufacturing scale, faster build cycles, and cost discipline. All accurate—and still insufficient. Comparative advantage explains why there should be trade; it does not explain why co-investment stalls. The binding constraint is no longer whether joint EU–AP projects are efficient in theory, but whether each side can credibly claim a fair share of the synergy rent: grid savings, lower levelised costs, faster permitting unlocked by standardisation, and market access premia. Both sides want to "buy low" from the other—Europe on labour-intensive manufacturing, Asia on intellectual property and finance—yet neither wants to "sell low." That standoff is rational under today's rules. The policy reframing is to move from price haggling to surplus-sharing: embed instruments that quantify benefits ex-ante, allocate them transparently, and pay them out automatically as real-world decarbonisation shows up in meters and customs codes. This shift in approach holds the promise of mutual benefits, providing a hopeful outlook for the EU-Asia Pacific Pact.

The numbers behind the unrealised gains

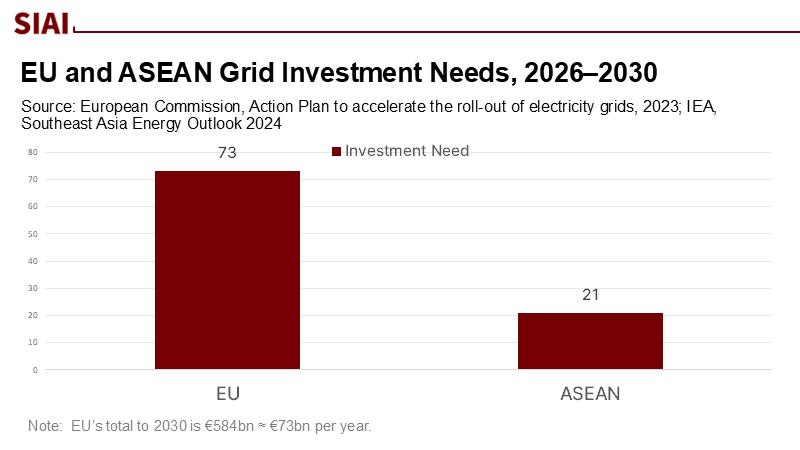

The investment backdrop is both generous and unforgiving. Global energy investment is expected to exceed USD 3 trillion in 2024, with USD 2 trillion allocated to clean energy technologies and infrastructure—funds that will drive clarity and bankable rules. Lithium-ion pack prices fell to USD 115/kWh in 2024, marking the steepest annual drop since 2017, driven by overcapacity and lower input costs. Renewable capacity additions reached a record 585 GW last year, bringing the total installed renewable energy capacity to ~4,448 GW. Europe's bottleneck is infrastructure: the Commission's Grid Action Plan identifies €584 billion in grid investment needs by 2030, while ENTSO-E estimates that each euro invested saves more than two euros in system costs. In Southeast Asia, electricity demand is expected to rise rapidly, and the IEA forecasts approximately USD 21 billion in annual grid investment needs from 2026 to 2030. Meanwhile, Europe imported €19.7 billion in solar panels in 2023 and relies heavily on Asian manufacturing, where China alone controls over 80% of solar PV manufacturing stages. The benefits of more efficient and equitable EU-Asia Pacific green energy cooperation are apparent; however, the proposed mechanisms to implement them are not yet in place.

Instrument one: cross-border carbon contracts for difference

Start with a price-anchored co-investment tool: cross-border carbon contracts for difference (xb-CCfDs). Under an xb-CCfD, an EU–AP facility pays the gap between a reference carbon price and verified abatement costs in a partner project—say, green steel in Vietnam, grid-firming storage in the Philippines, or renewable-powered data centres in Malaysia—provided output flows into EU-aligned value chains with robust measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV). Crucially, both sides contribute in proportion to the benefits they capture: Europe monetises avoided CBAM liabilities and security-of-supply value; AP partners monetise employment, exports, and technology learning. To maintain clean incentives, the reference price can be a moving average of EU ETS futures or an agreed-upon synthetic index; payouts are reduced automatically as costs decrease. Tie eligibility to traceable power schedules and lifecycle baselines, and add a sunset clause once costs converge. The xb-CCfD makes the "pie" calculable upfront, removing the incentive to hold out for a better bilateral price later.

Instrument two: interoperability of taxonomies and standards

Surplus-sharing requires information symmetry. That means green labels that travel. Europe's Sustainable Finance Taxonomy and ASEAN's Taxonomy Version 2—which became effective with an update in February 2024 and introduced a more ambitious "Plus Standard" with technical screening criteria—are converging in spirit but not yet interoperable. A mutual-recognition protocol could enable AP projects that meet Plus-Standard-equivalent thresholds for lifecycle emissions, grid-emissions factors, and transition pathways to qualify automatically for EU-aligned finance and procurement. Portable, machine-readable disclosures (digital product passports) would sit on top, linking customs codes to carbon attributes, providing a clear and transparent view of the carbon footprint. Grids are another standard for alignment: shared grid codes and interconnection criteria reduce permitting delays and curtailment risk, directly increasing the expected value of projects funded under xb-CCfDs. The point is not to erase differences; it is to set a credible floor that mobilises private capital without re-litigating "what counts as green" at every border.

Instrument three: CBAM credits for verified joint decarbonisation

Europe's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is set to enter its definitive phase in 2026. It aims to align import prices with EU carbon constraints, rather than to restrict trade. A targeted pilot could allow importers to offset a portion of CBAM certificates with "partnership credits" earned by financing verifiable emissions reductions in AP supply chains tied to their products—such as hydrogen, aluminium, cement, and steel—provided those reductions are measured against EU-quality baselines and audited by accredited verifiers. Cap the credit share, sunset it after five years, and require co-funding from an EU–AP window to avoid pure arbitrage. This would transform CBAM from a perceived unilateral tax into a two-way decarbonization instrument, while preserving environmental integrity. It is a pragmatic bridge: the EU keeps the price signal; AP producers gain a pathway to compliance that rewards early action rather than penalising geography.

The corridors where cooperation gets real

Synergy becomes visible in places, not communiqués. Consider shipping and data. The Singapore–Rotterdam Green and Digital Shipping Corridor now links 28 partners across the container value chain, piloting low-carbon fuels and data standards, and even completing mass-balanced biomethane bunkering trials. That is a living template for EU–AP xb-CCfDs attached to fuels with robust MRV. On land, Southeast Asia's electricity demand is projected to increase from just over 1,300 TWh today to more than 2,000 TWh by 2035 in the IEA's STEPS scenario, driven by buildings (notably air conditioning), followed by transport and industry—precisely where European grid expertise and flexibility markets are expected to have an impact. If we route verified green electrons and molecules from ASEAN producers into European offtake with digital traceability, the corridor becomes a pipeline of bankable emissions cuts, not a press release about friendship. That is where "comparative advantage" stops being a slogan and becomes a spreadsheet.

The finance stack that makes the split real

Public money must set the rules and absorb early risk; private balance sheets will do the scaling. The EU's Global Gateway aims to mobilise up to €300 billion by 2027 across connectivity, climate, and energy. The EIB had a record energy year in 2024, financing more than €28 billion in the sector worldwide, while ADB and AIIB expand climate windows across Asia. In 2024, the heads of multilateral development banks committed to aligning their procurement approaches to facilitate co-financing, a small yet significant technical change with a substantial impact on blended deals. A practical stack for an EU–AP battery-grade materials project might combine an ADB senior loan with an EIB guarantee, XB-CCfD revenue support indexed to the EU ETS, and a mezzanine tranche from a Team Europe vehicle—crowding in long-term private debt for the grid connection and flexibility assets that make up the offtake firm. The policy point: finance follows credible pipes, standards, and price anchors. Put those in place, and the capital is already waiting.

Answering the predictable objections

Three objections recur. First, sovereignty: why should Europe tie its standards to others, or Asia concede IP rents? Because mutual recognition is not mutual surrender. It is a floor, not a ceiling; if an AP asset meets a Plus-Standard-equivalent screen, it qualifies—if not, it does not. IP pools can exclude crown-jewel patents while licensing process know-how under FRAND-style terms. Second, leakage: won't low-cost imports swamp EU producers? Here, CBAM is precisely the firewall, and pairing it with partnership credits incentivises early decarbonisation rather than blunt exclusion. Third, affordability: can grids and flexibility be funded fast enough? The Commission's €584 billion grid estimate by 2030 is daunting, but ENTSO-E's finding—that each euro saves more than two euros in system costs—means delay is the expensive option. Aligning ASEAN and EU taxonomies reduces transaction costs further by making disclosures portable for lenders. The cheapest power system is the one we actually connect.

What this means for classrooms, ministries, and boards

Educators should train for a world where a shipping document is also a carbon instrument. Curricula need power-systems basics, lifecycle accounting, and trade law in the same room; students must be able to read a grid-code diagram and a CBAM report. Administrators should redesign procurement to accept XB-CCfDs and taxonomy portability, writing tenders that include pricing resilience and machine-readable emissions data as deliverables, rather than as footnotes. Policymakers should pilot the CBAM crediting mechanism in two sectors—steel and aluminium—where MRV is mature and export stakes are high. They should route Global Gateway capital into cross-border grid upgrades that unlock private IPPs. Shipping corridors, such as the Singapore–Rotterdam route, demonstrate how public rule-setting can de-risk entire supply chains; the same logic can be extended to green hydrogen and e-fuels, utilizing digital product passports to track lifecycle emissions into European customs systems. Translate standards into contracts, and learning curves will do the compounding.

Stop arguing about price; design the split

The shift is no longer limited by technology news; institutional frameworks hinder it. The data from 2024—USD 2 trillion allocated for clean energy, unprecedentedly low battery costs, and a 585-GW increase in renewable capacity—indicate that the hardware is prepared. ENTSO-E's grid-savings ratio of over 2-to-1 shows that the economics are favorable if we construct the necessary infrastructure; the Commission's requirement of €584 billion and ASEAN's annual need of USD 21 billion highlight where we should begin. What hinders advancement is the apprehension that one party will benefit financially while the other foots the expense. Cross-border CCfDs, taxonomy interoperability, and CBAM partnership credits are not ultimate solutions; they are the three components that convert comparative advantage into shareable surplus. When combined, they enable the EU–AP partnership to become the primary driver of the green transition, primarily as the United States' incentives, focused on domestic content, look inward rather than fostering collaborative frameworks. The only way to resolve the "buy-low/sell-low" deadlock is to pre-negotiate the division—and then allow projects to proceed.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Asian Development Bank. (2025). AIIB Annual Report 2024 (selected Asia climate finance context).

BloombergNEF. (2024, Dec 10). Lithium-Ion Battery Pack Prices See Largest Drop Since 2017, Falling to $115/kWh.

Clingendael Institute. (2024, Aug). Plugging Green Power into the EU-ASEAN Partnership.

ENTSO-E. (2025). TYNDP 2024 materials & System Needs Study workshop ("each euro invested saves >2 euros").

European Commission. (2023, Nov 28). Action Plan to accelerate the roll-out of electricity grids (press release; €584bn by 2030).

European Commission. (n.d.). Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) (definitive phase in 2026).

Eurostat. (2024, Oct 14). International trade in products related to green energy (EU imported €19.7bn in solar panels in 2023).

IEA. (2024, Jun). World Energy Investment 2024 (USD 3T energy; USD 2T clean energy).

IEA. (2024, Oct). Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2024 (demand to >2,000 TWh by 2035).

IEA. (2023–2024). Solar PV Global Supply Chains (China >80% share of manufacturing stages).

IRENA. (2025). Renewable Capacity Statistics 2025 (585 GW added; 4,448 GW total).

Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore & Port of Rotterdam. (2025, Mar 25). Joint media release: Strengthening collaboration on Green & Digital Shipping Corridor; (2024, Nov 28) biomethane pilot.

UNEP FI / ASEAN bodies. (2024). ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance Version 2 (effective update Feb 19, 2024) and related guidance.

WEF. (2024, Jul 3). How Southeast Asian countries can cooperate to enhance grids (IEA estimate: ~USD 21bn annually, 2026–2030).

U.S. Treasury/IRS. (2024–2025). Domestic Content Bonus Credit guidance and safe harbors (domestic-content orientation).