From Grand Gestures to the Profit Test: How China’s Friendlier BRI Can Work in Central Asia

Input

Modified

China is softening its BRI approach in Central Asia with grants and joint ventures The key challenge is making infrastructure projects financially self-sustaining Only profitable corridors can secure lasting partnerships and stability

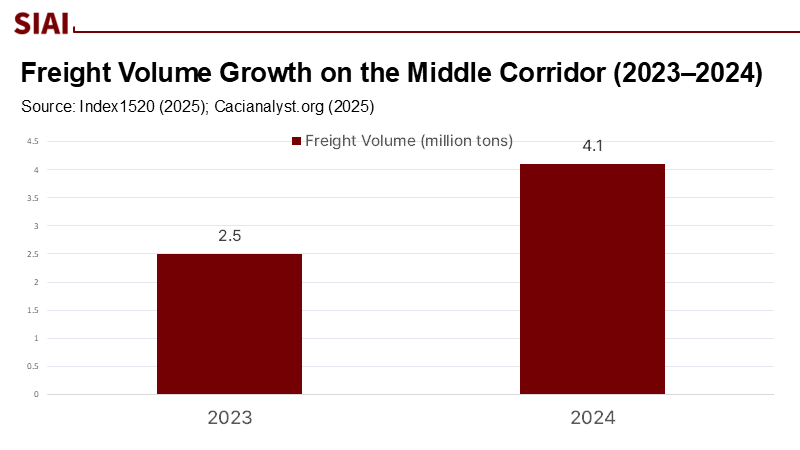

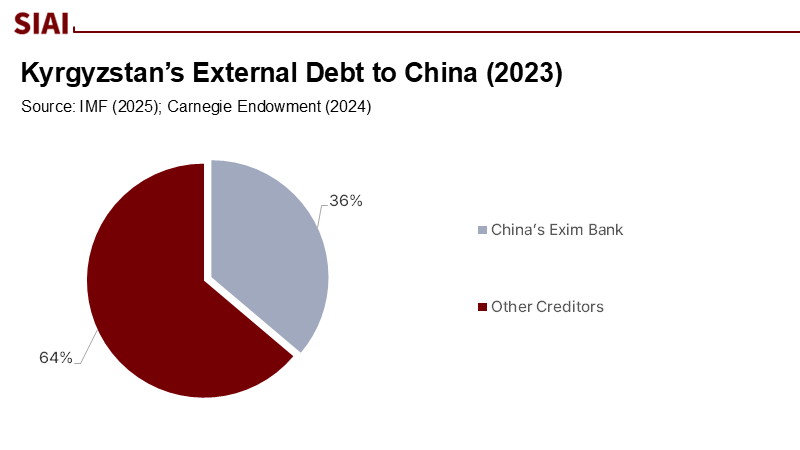

In June 2025, Beijing shifted its approach to Central Asia by committing RMB 1.5 billion in grants to the five countries, marking a departure from aggressive state-to-state lending. This coincided with a 63% increase in rail volumes along the Trans-Caspian “Middle Corridor” in Kazakhstan and a 14% rise in China-Europe freight trains through Xinjiang. However, Kyrgyzstan faced a US$1.7 billion debt to China’s Exim Bank, making up 36–37% of its external liabilities. This highlights the need for policies that encourage financially sustainable relationships, where infrastructure generates its own returns through operating profits and local investments, rather than relying on continuous bailouts.

Reframing the argument: from geopolitics to cash flows

The prevailing narrative has revolved around geopolitical strategy—Russia’s war disrupting routes, Europe courting the region, and China consolidating its influence. While these factors are indeed significant, they present an incomplete picture of the situation. The policy frame now needs to pivot from “who funds and builds” to “who earns and keeps.” This means evaluating projects not merely as symbols of alignment, but as engines that generate predictable, ring-fenced cash flows for host operators. The rationale is clear. After a decade of mixed outcomes and reputational damage, Beijing’s recalibrated Belt and Road initiative now prioritizes “small yet beautiful” projects and enhanced risk controls.

Meanwhile, Central Asian governments, grappling with tighter fiscal constraints and IMF advice to curb quasi-fiscal losses, are increasing energy and rail tariffs to achieve cost recovery. In other words, the geopolitical dance is already veering towards operational economics. A policy that accelerates this convergence—co-financed ventures, service-level standards, and regulated revenue sharing—will transform goodwill into durable capacity. Otherwise, today’s bridge-building will remain politically expensive and financially brittle.

The corridor is moving; margins still decide

Traffic growth is real. The Middle Corridor’s tonnage expanded rapidly in 2024, with estimates ranging from 4.1 million tons in the first eleven months to about 4.5 million tons for the whole year. Georgia’s rail operator reports freight revenue of roughly 0.12 GEL per ton-kilometer in 2024, with operating expenses at nearly 0.13 GEL, suggesting that even with rising volumes, sustained profitability requires productivity gains and tariff discipline. Meanwhile, Uzbekistan announced a 30% increase in domestic rail freight tariffs in late 2024 and has begun cutting energy subsidies, with cost-recovery timelines through 2026 for power and heat. The pattern is unmistakable: volumes are rising, but whether Central Asia’s operators escape fiscal drain depends on pushing unit revenues above unit costs and keeping them there. The policy priority is not another ribbon-cutting; it is urgent governance that standardizes performance metrics—ton-km yields, on-time rates, asset-turnover ratios—across the corridor and ties future financing tranches to those metrics.

The new financing playbook: joint ventures, tariff reform, and targeted grants

If the last decade’s emblem was the sovereign loan, the next one is the blended deal. The China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) railway is moving forward under a joint company, where China holds 51% and Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan each hold 24.5%—an ownership design that shares upside and governance, rather than outsourcing both to a foreign EPC contract. At the same time, Europe’s Global Gateway has pledged €10 billion for the Trans-Caspian corridor and added a further €12 billion in 2025, channeling multilateral standards on procurement and state-aid into the region’s logistics. Beijing’s own pivot includes not only equity-like structures but outright grants—exactly the benevolent capital that critics said was missing—and cooperation via AIIB on policy-linked lending that rewards tariff and regulatory reforms. The outcome should be complementary, not zero-sum: JV stakes and grant-aided service upgrades on the eastern legs, plus EU-backed modernization and de-bottlenecking westward, all benchmarked to corridor earnings.

What profitability looks like: a transparent back-of-the-envelope

Consider a stylized rail link that aims to handle 12 million tons annually across a 500-kilometer segment—figures consistent with planned upgrades and medium-term ambitions on Middle Corridor spurs. Suppose average freight yields are aligned with Georgia’s recent reported order of magnitude, translated to a neutral regional proxy of US$0.03–0.04 per ton-km once currency and product-mix differences are acknowledged. At 12 million tons and 500 km, this produces roughly 6–8 billion ton-km; at US$0.03–0.04 per ton-km, the gross freight revenue would be US$180–320 million per year. If operating expenses track 85–95% of revenue before depreciation and interest, EBITDA could range from US$9 million to US$48 million. A US$4.7 billion capex envelope—the public estimate often cited around the CKU—would require concessional capital, long tenors, or regulated tariff escalators to bridge the viability gap. Two policy levers matter most: first, reducing dwell times and transshipment losses to increase asset turns (each 10% gain in ton-km per wagon-day reduces unit costs meaningfully); second, ring-fencing corridor cash flows so tariffs can adjust predictably without political resets. These are estimates, not predictions, but they surface the crux: profitability is built as much in operations and regulation as in concrete.

Implications for educators, administrators, and policymakers

Education systems have a direct role in whether these corridors become fiscal assets rather than liabilities. Universities and technical institutes should establish interdisciplinary programs that integrate transport economics, power-sector tariff design, and data operations, training a cadre of corridor managers who can price services to cost and negotiate performance-based contracts. Public administration schools should integrate modules on PPP governance and sovereign risk management, drawing on IMF and multilateral case material from the region’s energy and rail tariff reforms. Ministries and SOEs can partner with AIIB and EBRD to create in-service academies that credential dispatchers, port planners, and revenue controllers on shared KPIs, with salary progression linked to on-time performance, wagon-turnaround, and collection efficiency. Policymakers should institutionalize this talent pipeline through corridor authorities that publish monthly dashboards—ton-km yields, OPEX/ton-km, and tariff pass-through schedules—so that external financiers release funds against measurable improvements rather than political milestones. In short, capacity building is not a side project; it is the profitability engine.

Answering the critics: debt traps, detours, and the Europe question

Skeptics argue that the BRI’s structural flaws are too deep and that Europe has moved on. They are partly right: early-phase risk management was weak, and several high-profile projects stumbled. Italy’s 2023 exit embodied European disenchantment even as Brussels re-entered Central Asia on its own terms. However, today’s evidence suggests a competitive convergence rather than a retreat. Beijing’s smaller, more bankable deals, its use of grant finance in 2025, and JV structures, such as the CKU, indicate a shift away from pure sovereign leverage.

Meanwhile, the EU’s €10–12 billion corridor commitments and EIB loans to Kazakhstan’s transport upgrades demonstrate that the region’s westward links are being financed with standards Central Asian governments broadly want to meet. The risk is not that one side dominates the other; it is that host-country operators fail the profit test and end up with politically symbolic but fiscally weak assets. Clearer lender classifications in restructurings, tariff paths to cost recovery, and transparent cash-flow waterfalls are the practical antidotes.

A corridor built to last: operational KPIs as statecraft

The strategic case for China-Central Asia connectivity is durable: it diversifies routes away from Russia, shortens transit by thousands of kilometers for certain cargoes, and binds the region into overlapping European and Asian value chains. Yet, sustainable statecraft now runs through dispatch centers as much as it does through summit halls. The fastest way to anchor trust is to codify corridor KPIs into treaty-adjacent documents: minimum on-time performance, maximum dwell, published tariff escalators, and audited revenue-sharing between JV partners. Grants can unlock early bottlenecks, but they should be tied to service-level reforms; policy-based lending can support tariff transitions if combined with targeted social protection. Finally, when debts do require relief, China’s growing participation in multilateral restructuring norms—and proposals for centralized management of problematic sovereign loans—should be leveraged to protect operational budgets, ensuring that maintenance is not the first casualty of fiscal stress. The goal is not just alignment; it is cash-positive alignment.

Tie back to the metric that matters

The primary focus should be on the monthly cash-flow statement, rather than the headline grant or treaty language. Central Asia’s railways and power systems are finally making progress—with increased volume, improved incentives, and a broader range of financiers—but they will only maintain their alliances if they sustain their margins. This marks a significant shift in China’s regional strategy: moving from an imperial viewpoint to a more patient, supportive co-financing model that accepts modest early returns to establish viable operations. Host governments must also adopt this shift: implementing tariff reforms with protective measures. This equity in joint ventures allows them a stake in discussions and corridor authorities that disclose the critical figures. If, by the end of the next two years, operating expenses per ton-kilometer consistently fall below revenue per ton-kilometer along the corridor, and if grants and loans are tied to that metric, the political landscape will take care of itself. The evaluation is surprisingly straightforward. Self-sustaining assets maintain relationships.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). 2024. Accelerating the Uzbekistan Climate Transition for Green, Inclusive and Resilient Economic Growth—Subprogram 1 (Board Approved Project Document). November 25, 2024.

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). 2025. Annual Report 2024. July 1, 2025.

Cacianalyst.org. 2025. “The Middle Corridor Remains Supplementary to Major Trade Routes Between the EU and China.” April 30, 2025.

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. 2024. “Chinese Lending Adapts to Central Asia’s Realities.” August 19, 2024.

Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). 2023. “The Rise and Fall of the BRI.” April 6, 2023.

CSIS. 2023. “Italy Withdraws from China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” December 14, 2023.

Diplomat, The. 2024. “A Ceremonial Start to Construction of the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway.” December 27, 2024.

EEAS (European External Action Service). 2024. “Global Gateway: €10 billion commitment to invest in Trans-Caspian Transport Corridor.” January 28, 2024.

Georgian Railway. 2025. Investor Presentation: 2024 and Q4 2024 Audited Results. June 2025.

IMF. 2024. Regional Economic Outlook: Middle East and Central Asia, April 2024. April 18, 2024.

IMF. 2025. Kyrgyz Republic: 2025 Article IV Consultation—Press Release. June 4, 2025.

Index1520. 2025. “The Trans-Caspian International Transport Route and other promising corridors in Central Asia.” January 31, 2025.

RailFreight.com. 2024. “Wave of rail fee increases also reaches Uzbekistan: 30% hike coming soon.” November 14, 2024.

Reuters. 2025. “China’s Xi signs treaty to elevate ties with Central Asia.” June 17, 2025.

State Council of the People’s Republic of China. 2025. “Full text of Xi’s keynote speech at the Second China-Central Asia Summit.” June 18, 2025.

Wang, C.-N., & Nedopil, C. 2023. Ten years of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): “Small is Beautiful”? Boston University Global Development Policy Center, October 2023.

Xinhua/PRC Government portal. 2025. “Major Xinjiang ports handle over 4,000 China-Europe freight trains in the first five months; 16,400 in 2024.” May 31, 2025.

Comment